The Shahnameh: Persian miniatures

By Tarun Nagesh

Artlines | 2-2023 | June 2021

Through the Henry and Amanda Bartlett Trust, the Gallery recently acquired ten miniature paintings from a volume of the Shahnameh, or ‘Book of Kings’, by the Persian poet Abu’l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020CE). As Tarun Nagesh notes, the epic poem captures the lives and stories of the ancient Iranian kings, from the creation of the world to the Arab conquest of Iran in 642.1

The Shahnameh — one of the most celebrated and influential achievements of Persian culture — was completed in 1010CE. The ‘Book of Kings’ comprises more than 50 000 couplets, which took its creator, Abu’l Qasim Firdausi, roughly 33 years to compile. He dedicated the epic to the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud of Ghazni (r. 998–1030) who, by the end of the tenth century, had succeeded in gaining power over eastern Iran and modern-day Afghanistan. However, the ruler responded with little enthusiasm; according to some sources, before he died, a poor and sick Firdausi voiced his disappointment over the little compensation he received for the work in a harsh satire of the sultan.2

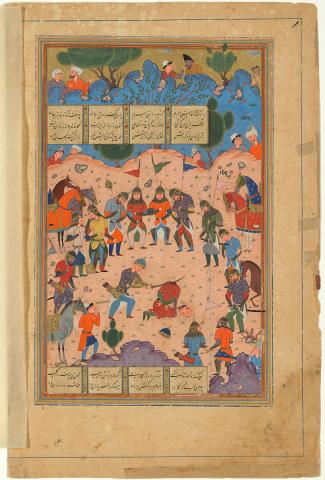

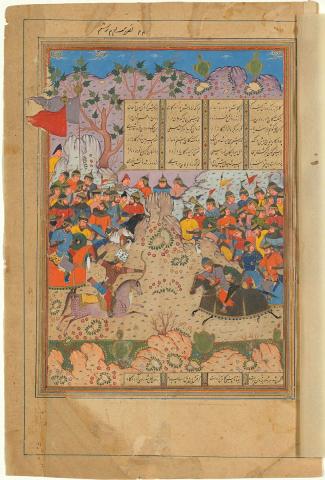

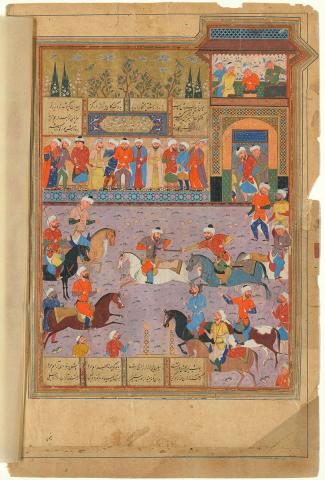

Despite this history, the Shahnameh became enormously popular with both foreign and local rulers of successive dynasties, who continually commissioned new copies of the epic and commonly adapted the text’s ideas and values to suit their own plights and ideologies.3 The many manuscripts produced were often highly illuminated and lavishly illustrated, which has since become a major tenet of classical Persian painting. Throughout the centuries these have featured numerous and varied depictions of the historical kings and their courts, great conquests, heroes slaying demons, battles of good over evil, and stories that conveyed the conduct and morality of rulers.

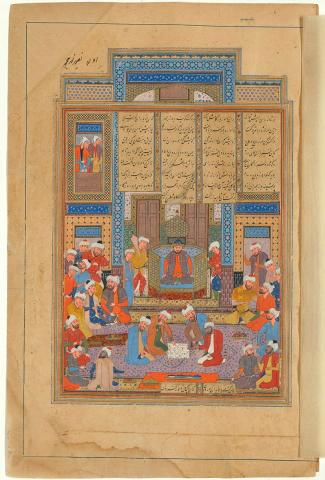

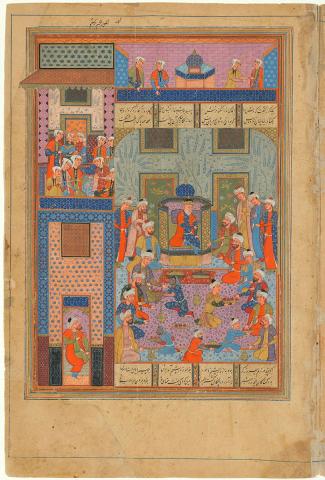

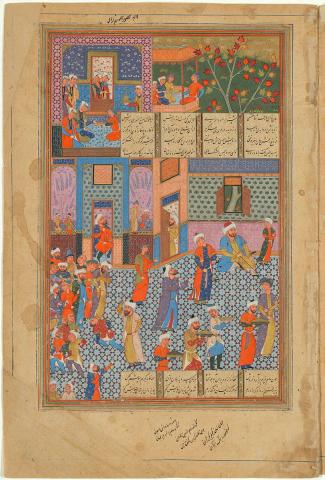

Across several sections of a Shahnameh volume thought to have been compiled in Shiraz during the Safavid dynasty (1502–1736), ten richly detailed illustrations exemplify the dramatic narratives and visual splendour for which the genre is now known. Encased between leaves of calligraphy broken by colourful sections of floral and geometric decoration and colourful banded borders, the vivid illustrations feature interior views compound, with a crowd of guests gathering in the different spaces, interspersed by servers and guards. The lively events are punctuated by views through windows where private interactions are taking place, and a garden is glimpsed through breaks in the patterned tiling. In the foreground of one of the paintings, women in headscarves prepare trays of food in front of a nobleman and his guest seated on a carpet in the centre and attended to by servants while groups of figures are spread through the architectures, peering over balconies or tightly framed in windows at a slightly further distance.

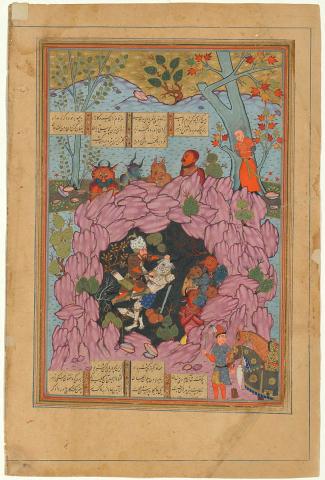

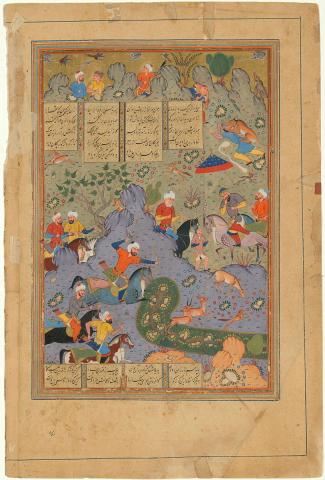

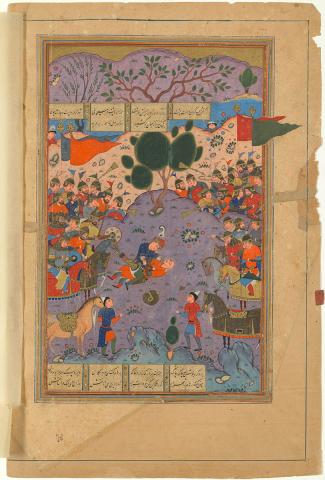

Captured across several other paintings are the popularly retold exploits of Rustam, one of the great heroes of the Shahnameh epic and Persian mythology, recognisable by his leopard-head helmet. One image depicts the tale of Rustam entering a darkened cave to kill the white demon, while a separate image recounts the tragic end of the long battle between Rustam and Esfandiyār — in which Rustam finally discovers the only way to kill the other heroic warrior is with an arrow, made from the branch of a tamarisk tree, to the eye.

Detailed in another painting is the story of chess being introduced to Iran at the court of Sasasian Kin Khosrow, when an envoy sent by an Indian ruler challenged the king to learn the game in an attempt to avoid paying a tribute. The clever young vizier Buzurjmihr manages to decipher the game, surrounded by court officials watching on.

The series illuminates just some of the fascinating histories and narratives of Persian history included in the Shahnameh. The glory of the kings, demonic tales and stories of grand achievements and defeats reveal what may have inspired Firdausi to embark on such a mammoth publishing task, and the reason why its stories have been celebrated and so popularly illustrated throughout history.

Tarun Nagesh is Curatorial Manager, Asian and Pacific Art, QAGOMA.

Endnotes

- Metropolitan Museum of Art [online resource], ‘Art of the Islamic world’, viewed 23 August 2022.

- Francesca Leoni, The Shahnama, Metropolitan Museum of Art [online resource], viewed 23 August 2022.

- Leoni, The Shahnama.