Nagasaki-e and Kaika-e: Japanese woodblock prints

By Abigail Bernal

Artlines | 1-2023 | March 2023

QAGOMA recently acquired a group of seven woodblock prints representing Nagasaki-e and Kaika-e, made during the Edo (1615–1868) and Meiji (1868–1912) eras, with funds from the Henry and Amanda Bartlett Trust. As a group, these lively images signal Japan’s radical transition from a closed economy to a modern, industrial nation, writes Abigail Bernal.

Europeans first came to Japan in the 1540s and were initially welcomed. However, the Tokugawa shogunate grew concerned by news of Spanish colonisation in the Philippines, as well as the early popularity of Christianity in Japan. In 1641, the shogunate issued a series of edicts (officially termed Sakoku, or ‘closed country’) that limited trade and diplomatic contact. Sakoku prohibited Japanese citizens from travelling abroad, or entry for foreigners without special permission, on penalty of death.

The port city of Nagasaki remained open to limited and officially sanctioned trade with small groups of Dutch and Chinese from 1641 to 1859, giving rise to the Nagasaki-e (Nagasaki School prints).1, 2 These prints often depicted foreign ships — the Chinese and Dutch vessels allowed to enter — as well as the people who came on them, their customs and mode of dress. Artists used natural pigments such as vermilion, red lead and indigo (the full range of colours, using multiple blocks, had not yet been developed). Sold by specialised publishers or booksellers in Nagasaki, Edo and Osaka, they were popular with both traders and curious residents — demonstrating ‘that although the country’s policy was to resist cross-cultural interaction, these encounters were happening nonetheless’.3 The genre declined in the late 1850s, when Yokohama replaced Nagasaki as a treaty port for foreign trade.

In 1854, the Treaty of Kanagawa ended the country’s 250 years of isolation and precipitated a change in government. By 1868, the last Shogun had resigned, and the Meiji era began. The Meiji Government focused on building transportation and communication networks, and on increasing its economic power by establishing factories and industry. Rapid modernisation was fuelled by the fear of becoming a colony under the control of a European nation.

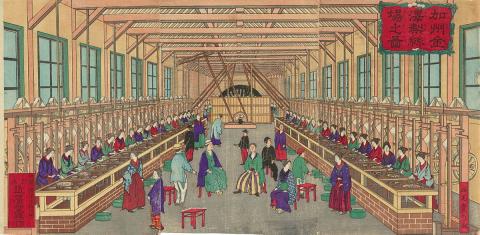

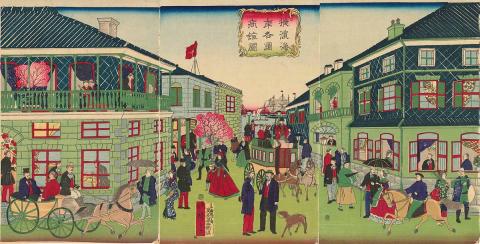

A new genre of prints known as Kaika-e, or ‘prints of enlightenment’, emerged around 1868 and were produced into the 1890s, becoming ‘a popular vehicle to introduce specific symbols of modernisation and scenes of the changing Meiji civilization and cityscape’.4 The government encouraged the printing of these scenes and also published their own educational or instructive kaika-e. The use of imported aniline colours, including vibrant reds and greens, is indicative of the changing times.

Yoshitoshi’s View of the train at Takanawa 1871 celebrates the establishment of the railway line between Tokyo and Yokohama, officially opened by the Meiji emperor in 1872. Cities like Tokyo (where wood had been the predominant material for public and private dwellings) changed radically in appearance with the construction of Western stone building — including banks, department stores, government sites, factories and industrial buildings. Hiroshige III’s View of trading companies at Yokohama 1871 clearly indicates the end of the Sakoku, as trading companies begin to appear inside the city and the streets bustle with people and activity. Among lurid green buildings with splashes of red and indigo, Westerners and Japanese locals dressed in Western clothes are visible alongside the few still wearing traditional kimono.

The celebration of infrastructure and industry in Kaika-e can be seen as reinforcing the official stance of the government, but also importantly documented transformations in both custom and lifestyle at a time when old and new Japan intersected; and when the advanced techniques of Japanese printmaking collided with Western pictorial and visual languages and materials. In conjunction with the Nagasaki-e, these vibrant prints tell the story of a tumultuous and fascinating time in Japan’s long history and rich culture.

Abigail Bernal is Associate Curator, Asian Art.

Endnotes

- The earliest surviving Nagasaki-e dates from 1740 and printing blocks have been found that were carved in the 1720s.

- Some trade continued with Korea out of Tsushima Province and with the Kingdom of the Ryukyu Islands from Satsuma Province.

- Stephen Salel, Honololu Art Museum, viewed June 2022.

- Monika Hinkel, ‘Envisioning Meiji Modernity: Kaika-e’, Japan Society Proceedings, viewed June 2022