Aisha Khalid: Water has never feared the fire

By Tarun Nagesh

The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art November 2018

Persian and Mughal art are celebrated for their pursuit of splendour and refinement, lavish and luminescent materials, and techniques of rigorous precision and geometrical perfection, as well as a cultural history distinguished by symbolic devices and epic narratives. Aisha Khalid studied Persian and Mughal art forms in the former Mughal capital of Lahore. Her works display the refined skill of miniature painting, textile techniques taught to her from a young age, concepts from Sufi music and philosophy, and the grandeur of Mughal architecture and gardens that abound throughout the city. With knowledge of and access to these vernacular traditions, she has found ways to adapt and illuminate objects and meanings, while probing the boundaries of cultural convention. Khalid’s experimentations with scale and technique enhance the richness and depth of these traditions, and her subjects transform the courtly and regal nature of Mughal art into one that is politically, intellectually and emotionally relevant today.

Khalid formally trained in miniature painting at Lahore’s renowned National College of Arts, and for more than two decades, she has pushed the highly disciplined genre in new directions. In particular, she uses the medium to provide perspectives on femininity and the domestic lives of women in Pakistan. In her astute observations of her cultural surroundings, the artist creates vignettes of female figures, architecture and objects, while introducing scale and abstraction to the intimate figurative tradition.1

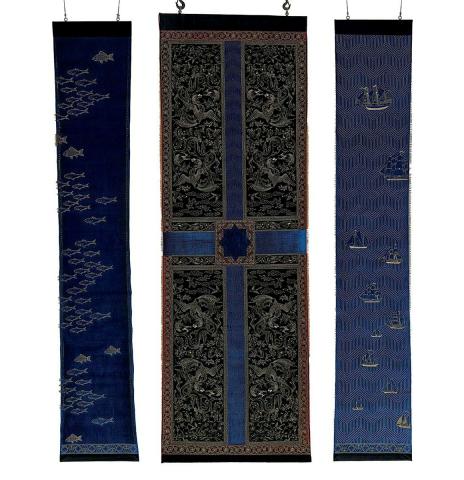

Recently, Khalid has been exploring the potential of textiles by drawing on embroidery and stitching techniques taught to her by her mother. She acknowledges the symbolism of the craft in women’s lives and domestic spaces today, while also introducing new approaches that challenge the conventions of the medium. In towering, suspended sculptural works, she imposes qualities of rigidity and danger to that which is normally intimate and tactile, recreating patterns inspired by Persian carpets and historical paintings on an architectural scale. The works are meticulously designed and created through labour-intensive processes, where enormous tapestries are stitched together with thousands of long gold-plated pins. With bold, shimmering surfaces, they hang like colossal rugs and reveal a multitude of symbols, patterns and motifs.

Taking its title from the words of the thirteenth-century Persian poet Rumi, Water has never feared the fire 2018 is a new work commissioned for APT9. Powerful in its scale and materiality, the work has been constructed on three hanging structures measuring nearly five metres high, with a design based on the quadrilateral garden layout of the Charbagh (‘four gardens’ in Urdu). The Charbagh is a manifestation of the quintessential Islamic garden from the Qur’an, and a principal symbol for paradise on earth, replete with symbolism and geometries that bridge the earthly and the divine. Four sections constitute the four gardens of paradise (for the soul, heart, spirit and essence), which are delineated by four water channels representing the four rivers of paradise also described in the Qur’an.2 Within the sections are glistening depictions of dragons and phoenix — creatures that appear widely in Persian art and feature in chapters of the historical epic The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings).3 The outer panels are composed of geometric designs that represent water patterns, in which sea creatures and ships are scattered, emblematic of trade and the movement of peoples and cultures.

With a rich knowledge of the technical and symbolic languages of centuries-old traditions, Aisha Khalid honours — but also challenges — how their principles operate in our world today. She contributes to their cultural evolution, while forming new avenues to translate their meanings to a contemporary audience. Tarun Nagesh

Endnotes

- See Virginia Whiles, Art and Polemic in Pakistan: Cultural Politics and Tradition in Contemporary Miniature Painting, Tauris Academic Studies, London and New York, 2010, p.43.

- Emma Clark, ‘The symbolism of the Islamic garden’, Islamic Arts and Architecture, 2 October 2011, viewed April 2018.

- The Shahnameh was written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi (c.940–1020).