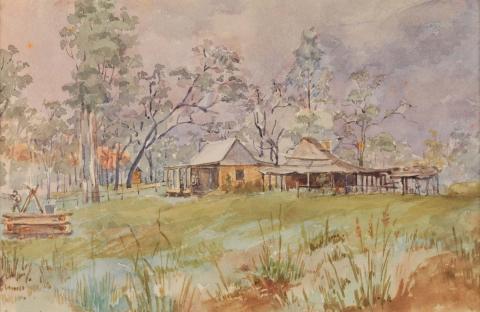

Neville-Rolfe gives us glimpses into domestic life on the Queensland station. In Clive and Mrs Mackintosh, an older lady nurses a boy, the artist’s nephew, who is dressed in a long cotton gown. The shelf behind them is decorated with a fine lace runner, a vase of flowers, a small ornamental box and a grand painting of a crane and parrot. Few settlers would have been able to afford items of such scale; early bark slab huts were more often decorated with pages from illustrated newspapers, concealing the gaps and keeping the wind out. For pioneer women, the homely touches depicted would have provided great comfort.

Even within such genteel scenes, we are reminded of the potential for violence on the colonial frontier. As the family gather around a table set with a white cloth, a young Indigenous man plays a banjo, and a bright lamp casts shadows from the three rifles arranged on the raw timber wall. Rifles were common, essential for food and protection from wildlife, but their prominence hints at the broader human conflict in the region, where groups of well-armed pioneers would ride out, often with settler-commanded Native Police, to ‘disperse’ Indigenous peoples — a code word to condone massacres of entire family groups. How much Neville-Rolfe knew of these concurrent events is uncertain; however, these scenes can be read from multiple viewpoints.