Picasso: ‘La Suite des Saltimbanques’

By Sally Foster

Artlines | 1-2015 | March 2015

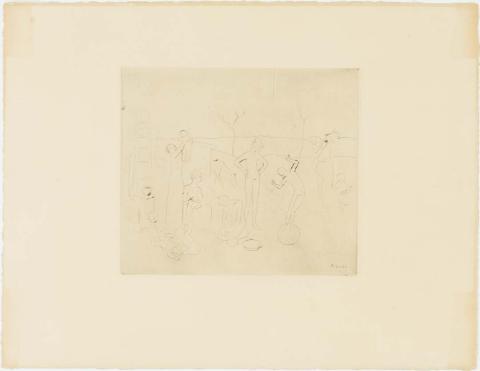

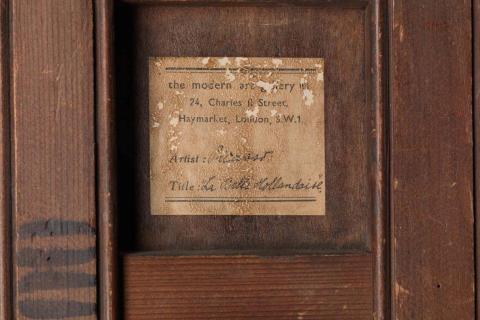

The etchings and drypoints known as ‘La Suite des Saltimbanques’, including our Le Repas frugal, Salomé, Le deux Saltimbanques, Tête de Femme de Profil and La Toilette de la Mère, were made immediately following 22-year-old Pablo Picasso’s move from Spain to France in April 1904. They mark an important period of personal and artistic transition in the artist’s life; created on the cusp of his ‘blue’ (1901–04) and ‘rose’ (1904–06) periods, ‘La Suite des Saltimbanques’ is integrally connected to Picasso’s paintings and drawings of the same period, including the Gallery’s La Belle Hollandaise 1905. These prints offer an extraordinary insight into the creative musings of a young artist on the brink of greatness, as well as insights into the social milieu Picasso inhabited after settling into a studio in Le Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre, Paris.

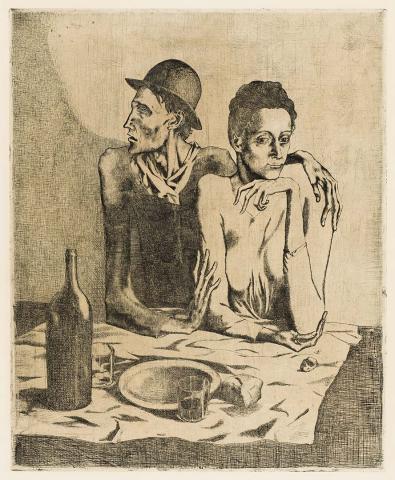

Picasso received no formal training in the techniques of printmaking, and it was not until August 1904 in Paris, when painter Ricard Canals (1876–1931) showed him the etching and drypoint process, that he became captivated by its possibilities. Le Repas frugal, created in September that year, was Picasso’s first serious attempt at printmaking — extraordinary when considered in light of his inexperience — and is one of the most renowned and frequently reproduced images of the artist’s early career. Depicting an emaciated French couple seated at a café table, Le Repas frugal references the gaunt features and elongated limbs of the subjects painted by Spanish master El Greco (1541–1614), who had a profound influence on Picasso’s painting during his ‘blue’ period. Le Repas frugal was a conspicuous attempt to translate this painterly style to the printmaking process, and established a critical link between Picasso’s Spanish past with his French future.

When Picasso made Le Repas frugal, it was with the intention of creating an edition of prints that would sell. Due to his poor financial situation, the print was made on a zinc plate that had previously been used for a landscape composition by Joan González (1868–1908), a Spanish artist who resided in the Le Bateau-Lavoir studios. The scraping down of the plate was not completely thorough and the remnants of the earlier composition can be seen in the tuffs of grass at the upper right of the image. Enlisting master printer Auguste Delâtre (1822–1907), a small first edition was pulled, but when no significant commercial interest was shown, Picasso abandoned the idea of printmaking as an alternative income source. Captivated nonetheless by the creative potential of the medium, over the course of 1905, Picasso created a series of delicate, even nominal etchings and drypoints of friends, acquaintances, roaming circus performers and family groups. Immediately recognising the unique qualities inherent to etching and drypoint, he used an economy and elegance of line that testified to his skill as a draftsman and proved his rapidly acquired command of the medium. As with Le Repas frugal, old plates were recycled and scraped down, resulting in scratch marks appearing (at times dramatically) throughout the series, inadvertently adding a wonderful modernity to the images.

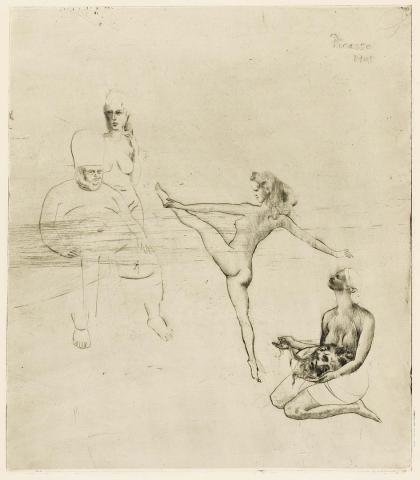

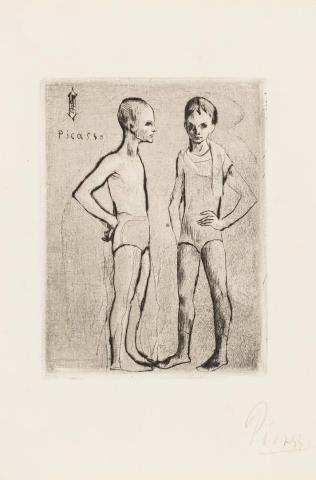

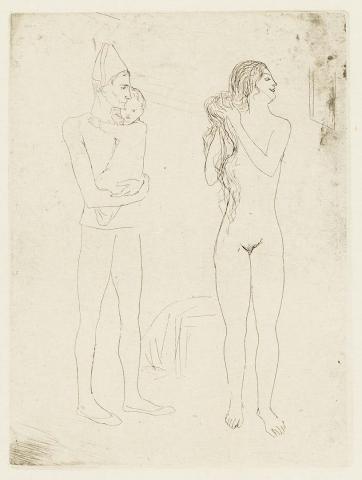

The order in which the prints were created is well documented.1 As such we know that, after making the stunning neoclassical portrait Tête de Femme de Profil in February, Picasso made Les deux Saltimbanques in March. This rare, signed impression is one of 12 printed in 1905 by Delâtre to be included as an illustration in selected copies of André Salmon’s (1881–1969) first collection of poetry, Poèmes (1905). Around May (during the northern European summer), Picasso travelled to Schoorl in the Netherlands to visit Dutch writer Tom Schilperoort for a month, during which time he painted La Belle Hollandaise, one of the most valuable works in the Gallery’s Collection, and which marks the artist’s turn to the depiction of more voluminous figures. Back in Paris between June and August, Picasso made the extraordinary Salomé. With its literary subject matter and dynamic composition, this important work reveals Picasso’s propensity for mythology and sexually explicit imagery. Finally, towards the end of the year, Picasso produced La Toilette de la Mère — one of a charming but wistful group of three delicate and simply rendered images that feature a couple with a baby.

Never intended at the time of their creation to be a formally issued suite, Picasso and Delâtre produced only a few impressions. In September 1911, influential art dealer Ambroise Vollard bought 15 plates from Picasso, which included these works and others, mostly depicting circus performers. In 1913, Vollard had the 15 plates steelfaced2 and enlisted printer Louis Fort to print an edition of 27 or 29 on Japon paper and an edition of 250 on Van Gelder Zonen wove paper. It was at this time that Vollard collectively titled the 15 unnamed prints ‘La Suite des Saltimbanques’ (‘Suite of acrobats’), and it was only following this that the works became widely collectable.

The mythology and iconography of circus performers, actors, acrobats and harlequins were immensely fascinating for artists and writers in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Identifying with the itinerate lifestyle of the déclassé entertainers, Picasso and his close friends repeatedly used images inspired by this subculture in their art and poetry. More broadly, what can be seen in ‘La Suite des Saltimbanques’ is that Picasso’s life and art were inseparable from the beginning, and throughout his career, friends and the women he had relationships with were an important factor in his creativity, his pictorial approach and his development as an artist. Writing in 1911, the American-born, Paris-based author and modern art collector Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) described Picasso in the following terms: ‘One whom some were certainly following was one who was completely charming’.3 Encapsulating in her opening sentence the dominate paradigm that followed Picasso throughout his life, Stein goes on to describe what Picasso created:

This one was always having something that was coming out of this one that was a solid thing, a charming thing, a lovely thing, a perplexing thing, a disconcerting thing, a simple thing, a clear thing, a complicated thing, an interesting thing, a disturbing thing, a repellent thing, a very pretty thing.4

This early, enigmatic modernist critique in many ways continues to sum up perfectly the exquisite and accidental ‘La Suite des Saltimbanques’.

Endnotes

- Georges Bloch, Picasso: Volume I – Catalogue of the Printed Graphic Work 1904–1967, Editions Kornfeld et Klipstein, Bern, 1975.

- Steelfacing is a process that makes printing plates more durable but reduces the velvety effect created by the metal bur that is pushed up during the drypoint process.

- Gertrude Stein, ‘Picasso’ (1911), republished in Ulla E Dydo (ed.), A Stein Reader, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois, 1993, p.142.

- Stein, p.143.

Connected objects

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject