Wunjayi (Today): Sonja and Elisa Jane Carmichael

By Katina Davidson

Artlines | 4-2021 | December 2021

Two vibrant new acquisitions made in collaboration between mother and daughter by Sonja and Elisa Jane Carmichael work to preserve contemporary Quandamooka fibre practices. Originally commissioned for the 2020 Tarnanthi Festival in South Australia, QAGOMA now brings these works — made from found materials on Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) — home to Queensland, writes Katina Davidson.

The environment, culture and intergenerational exchange are at the heart of two vibrant new acquisitions, Quandamooka djagan marumba (Quandamooka country is beautiful) 2020 and Wunjayi (Today) 2020. Part of a major collaboration between mother, Sonja Carmichael, and daughter, Elisa Jane Carmichael, the works were originally commissioned for the 2020 Tarnanthi Festival at the Art Gallery of South Australia. Sonja and Elisa are Ngugi women of Mulgumpin (Moreton Island), belonging to the Quandamooka nation that also encompasses Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island) and areas of the surrounding bay and mainland.

The Carmichael family has played an important role in the regeneration of Quandamooka weaving, and these latest acquisitions join six works already in the Collection. The most culturally significant are arguably those that demonstrate the loop and coil with diagonal knots — a technique unique to the region that was recently revived by Sonja after the discovery of a historic women’s bag (gulayi) bearing this design in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. This gulayi sat anonymously in storage for over a century. While the bag wasn’t able to be returned to its ancestral shores, the knowledge of its existence signified a huge step toward the revitalisation of unique weaving practices in the region.1 In an act of reclamation and healing, mother and daughter have worked to make new gulayi. Sonja describes the significance of this act:

Our Elders had very strong memories of the grannies weaving with ungaire [reed]. Their stories — and being reunited with gulayi and other ancestral weavings in collections — has strengthened my understandings. I remember the first time viewing the bags and studying the materials and techniques with our Elders at the University of Queensland Anthropology Museum. It was a moment of joy, but also sadness for the time of their absence. They came out of boxes, from dark stalls in the museum to a new life.2

The installation Wunjayi (Today) 2020 includes an ungaire gulayi with eugaries (pipis) and vessel; and an oyster spoon and string made with talwalpin (cotton tree) fibres. These objects are also tools created in order to interact with their environment, and are made from materials predominantly collected from the island. The act of collecting enabled the artists to monitor the environments for change, including pollution, weeds and debris.

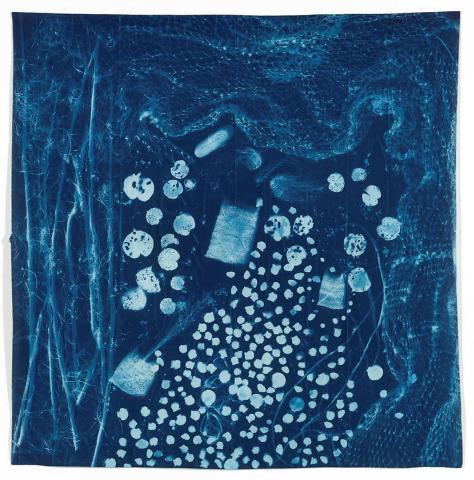

Quandamooka djagan marumba (Quandamooka country is beautiful) 2020 is a large-scale cyanotype print on cotton that entangles these objects in a sea of Prussian blue, recalling the landscape through atmospheric details. Quandamooka curator Freja Carmichael (daughter of Sonja and sister of Elisa) further explains that the cyanotype:

utilise[s] the photographic printing process as a metaphoric expression of the layered meanings and experiences embedded in the sands, lands, waters and cultural material. Each cyanotype [in the larger body of work] recalls a different story that speaks of colonial experiences. By sharing these histories, the overarching continuum of culture and connection to Country is highlighted.3

Invented in the 1700s to produce exact photogram copies, cyanotypes were used in the mid-1800s by Anna Atkins, whose Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843–53) ‘represent the earliest examples of books illustrated with photogenically produced images’.4 It is fitting that, hundreds of years later, these processes are being used as a way to capture a moment in time on Country.

Together, these works help to preserve contemporary Quandamooka fibre practices through their use of materials — natural and found debris from the shorelines of Minjerribah.

Katina Davidson is Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

Endnotes

1 Katina Davidson, ‘Present Surroundings, Elisa Jane Carmichael’ [catalogue essay], Onespace Gallery, Brisbane, March 2021, <https://onespacegallery.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/DIGITAL-Room-Brochure-Elisa-Jane-Carmichael_Present-Surroundings-26-March-24-April-2021.pdf>, viewed September 2021.

2 Freja Carmichael, ‘Wunjayi (today)’, in Tarnanthi [exhibition catalogue], Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2021, p.36.

3 Freja Carmichael, ‘Wunjayi (today)’, in Tarnanthi [exhibition catalogue], Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2021, p.36.

4 Dusan C Stulik and Art Kaplan, ‘Cyanotype: The Atlas od Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes’, The Getty Conservation Institute, 2013, <https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/atlas_cyanotype.pdf>, viewed September 2021, p.5.

Connected objects

Wunjayi (Today) 2020

- CARMICHAEL, Sonja - Artist

- CARMICHAEL, Elisa Jane - Artist

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject