Neolithic jars (China)

During China’s Neolithic period, which lasted from approximately 10 000 to 2000 BCE, societies evolved from a hunter–gatherer subsistence into more sophisticated, sedentary communities based around agricultural production and the domestication of animals. They emerged along the fertile tributary systems of the Huang He (Yellow) River in northern and central China and the Yangtze in the south and east.

The shift to a more settled lifestyle brought changes to both social organisation and material culture. Archaeological evidence suggests that the basic unit of social, political and economic organisation developed over this period from a single settlement into groups of villages. With this emerged social differentiation based on status and the development of specialist crafts and technologies such as pottery production.

To date, more than 7000 Neolithic sites have been discovered in China, and pottery finds have led to the identification of more than 30 distinct Neolithic cultures, each with their own unique traditions. The chronologies of and relationships between the cultures that comprise China’s prehistoric past are complex. There is some evidence of cultural and economic exchange between them, with recent archaeological finds and the use of advanced dating technologies providing new insight into the extent of influence, borrowings or overlap between the various cultures.

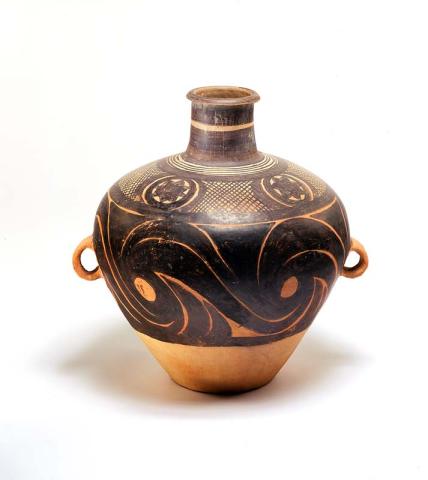

A number of cultures are represented in the Gallery’s Chinese Neolithic wares collection. These include the Banpo phase of Yangshao culture (4800–3600 BCE), represented by an elegant, elongated cord-marked jar; the Majiayao culture (c.3800–2000 BCE) represented by two jars decorated with bold geometric and curvilinear painted patterns; the Shanxi Longshan culture (c.2900–2000 BCE) which is represented by two tripod cooking vessels, one decorated with an impressed cord design, the other with an incised and appliquéd geometric design; the Qijia culture (c.2000–1600 BCE) which is represented with a narrow-necked jar with flared mouth and two vertical loop handles; and the Siwa culture (c.2100–1000 BCE) represented by a saddle-mouthed jar with tapered form and strap handles, the typical shape of the wares produced by this culture.

Neolithic pottery was fired at low temperatures in kilns that were dug into the ground. The wares represented in the Gallery’s Collection were handbuilt using sculpting, moulding and the ring-coil method, in which built shapes were smoothed using either the fingers or a small bat to beat out the coils against an anvil or pad placed against the inside of the pot. It is possible that some of the wares were finished by turning on a mat to form the mouths or apply decorative elements.

Together, these jars display a fascinating array of robust yet graceful forms, revealing the incipient sophistication of early Chinese pottery production that would develop into one of the world’s most spectacular ceramic traditions.

Sarah Tiffin, Artlines 1-2009, p.38.

Connected objects

Jar 2300-2000BCE

- SHANXI-LONGSHAN CULTURE - Creator

Jar 2000-1500BCE

- QIJIA CULTURE - Creator

Jar 1400-1100BCE

- SIWA CULTURE - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject