Empire and Image

The relationship between Britain and its colonies — in India, in particular — has a complex and contested history. Britain became an enormously powerful imperial nation during Queen Victoria’s reign (1837–1901). Conventional historiography divides British colonial and imperial rule into first and second empires. The first is considered to be Britain’s North American and Caribbean territories up to the War of Independence (1775–82), and the second, its domination in East Asia, the Pacific and Africa for most of the nineteenth century. Of course, the two phases overlap and the transition between them was gradual.

From 1815 to the end of the nineteenth century, Britain’s imperial power was at its zenith. While the history of British imperial reign — along with its military and political dimensions — has inspired volumes of analysis and interpretation, a partial picture of British trade and commercial enterprises can be traced through objects, images and domestic items.

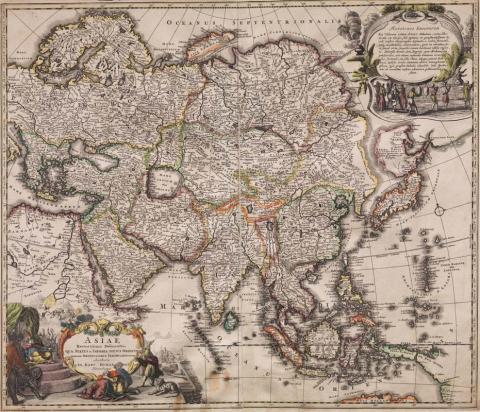

For European maritime nations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, mapping, navigating and formalising territories were activities central to their economic and political power. The first maps to include the ‘new world’ of the Americas began to appear in the sixteenth century. A synthesis of art and science, they combined cosmography, astronomy, and the arts of engraving and printing.

The recent acquisition of a celestial globe manufactured by English brothers John (c.1754–1835) and William Cary (c.1760–1825) and a map by Johann Baptist Homann (1664–1724) illustrate how imperial powers used the science of astronomy and cartography to create a particular world view. Homann’s map Asiae Recentissima Delineatio c.1716 creates a detailed territorial image of Asia as it was conceived in the eighteenth century, and includes the tip of Australia, then known as New Holland. Unlike a terrestrial map, the celestial globe charts the realm of star constellations and nebulae. The Cary globe includes elaborate figures of the zodiac depicted in a style typical of baroque taste: astronomy, revived by Arab scholars in the ninth and tenth centuries with translations of texts by Ptolemy, Euclid and Aristotle, informed the development of cartography in the sixteenth century.

Geography came to be regarded as a distinct scientific discipline in the nineteenth century with the establishment of the Société de Géographie in Paris in 1821 followed by London’s Royal Geographical Society in 1830. Atlases and maps were published in substantial quantities, and illustrated folios of prints depicting the fauna, flora and topography of colonial territories were produced. Auguste Logerot (c.1839–c.1880) was a map (and general-interest) publisher who worked with the cartographers and engravers of the period. One of his publishing specialties was the production of educational materials, including jigsaw-puzzle maps for children. The Atlas Geographique c.1880 depicts Nubian, Arabic, indigenous North and South American, Chinese and European children on the cover of the box, which contains jigsaw maps of France and Europe.

David Burnett, Artlines, no.4, 2010, pp.30–32.

This is an edited extract from 'Empire & Image', the ninth article in a series focusing on selected works from the Queensland Art Gallery’s international collection.

Connected objects

Cary's New Celestial Globe 1816

- CARY, John - Manufacturer

- CARY, William - Manufacturer

Atlas Geographique c.1880

- LOGEROT, Auguste - Creator