René Lalique: Seven glass vases

By Sophie Rose

Artlines | 3-2018 |

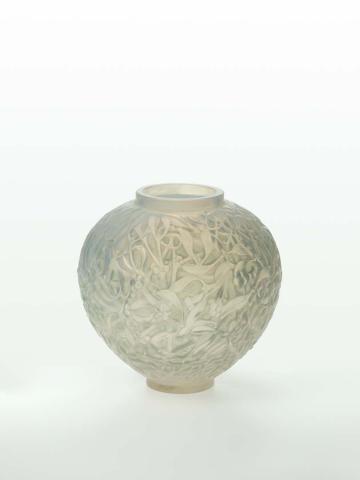

René Lalique’s glassware is instantly recognisable. It is opalescent and luminous, moulded with intricate patterns and motifs, and innovatively combines frosted and clear glass. Lalique’s creations were highly influential to both the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements, and they continue to inspire the decorative arts today. The Gallery is happy to announce the acquisition of seven rare Lalique vases. These works were purchased from the estate of the late Hans and Gertrude Mueller, who were some of the largest collectors of Art Nouveau design in Australia.

René Lalique was both an avant-garde craftsman and an astute industrialist. Originally trained as a jeweller, he discovered glass in the 1890s as a new medium to enhance his intricate designs.1 He soon turned exclusively to glassmaking, and in 1907 was commissioned to design perfume bottles for the famous Parisian perfumer François Coty. In 1921, he opened a glassworks in northeast France, which still runs today, almost a century on. The factory allowed Lalique to recast his designs in a variety of colours and finishes, from translucent clear or blue-green glass, to red and frosted grey. By the end of the decade, his factory was an epicentre of French decorative art, combining the seemingly disparate poles of luxury decor and mass reproduction.

This is perhaps the defining feature of Art Nouveau: its unashamed delight in ornamentation and everyday objects. Beginning in the 1890s, the style was decisively stylised and less detailed than the prevailing mode of Realism. Indeed, this was a truly pan-European movement, encompassing young artists and craftsmen from Brussels to Glasgow, Barcelona and Helsinki.2 Above all, this ‘new art’ was to evoke movement, with whiplash lines and dynamic compositions that mimicked the increasing speed of modern life.3

A strong curiosity for Japanese culture quickly became a facet of this ‘newness’. After a 220-year isolationist policy, or Sakoku, Japan opened its borders for trade in 1853. For the first time, Europe was exposed to an entirely new aesthetic tradition: a tradition that was not restricted to realism but founded on harmonious and restrained forms. Lalique was certainly inspired by Japanese art, although he cannot be said to match the enthusiasm of Japonism, in which painters, printmakers and furniture designers created pastiches of Edo-period artefacts.4

The earliest work in the group — Sauterelles (Grasshopper) vase designed in 1912 — is a fine example of Japanese-inspired design. Speckled with blue patina, the vase depicts grasshoppers resting upon intersecting reeds of grass. The grass in particular echoes the clumped reeds found in traditional Japanese screens (byōbu), as if Lalique has wrapped a paper screen around the moulded glass. Animal motifs appear again in the Perruches (Parakeet) vase 1919. The most detailed piece in the group, this delicate blue and white vase shows Australian budgerigars (a fashionable pet among the French elite at the time) perched upon flowering branches. Once again, we see the influence of Japanese tradition, albeit adjusted for European tastes. The perched bird is among the most common motifs in byōbu screens. Here, Lalique compresses the space between the birds so they form an interlocking pattern.

Spanning a 20-year period of production, the Gallery’s recent acquisitions reveal the development within Lalique’s oeuvre. In the final work of the group, the 1932 Davos vase, the glassmaker abandons figuration altogether. Made at the end of René Lalique’s career, this vase reveals the ebbing tide of Art Nouveau and the succession of geometric, urbanised Art Deco. The vase’s bulbous surface points to the next phase of twentieth-century design, in which the decorative aspirations of Art Nouveau would succumb to abstracted and utilitarian styles to follow. Indeed, the variety between the seven acquired vases is a testament to Lalique’s ability to absorb and adapt artistic trends. His name evokes timeless French refinement, marking a unique figure in twentieth-century art and design.

Endnotes

- Toyojiro Hida, ‘Japonism in Lalique’s Works’, in René Lalique, trans. Keiko Katsuya and others, Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Inc., Tokyo, 1992, p.39.

- Jeremy Howard, Art Nouveau: International and national styles in Europe, Manchester University Press, Manchester, NY, 1996, pp.2–3.

- Klaus-Jürgen Sembach, Art Nouveau: Utopia: Reconciling the Irreconcilable, Taschen, Köln, 2000, pp.8–22.

- Hida, ‘Japonism in Lalique’s Works,’ p.45.

Connected objects

Davos vase designed 1932

- LALIQUE, René - Creator

Oleron vase designed 1927

- LALIQUE, René - Creator

Beautreillis vase designed 1927

- LALIQUE, René - Creator

Druide vase designed 1924

- LALIQUE, René - Creator