Of Women: A new International Collection display

By Pippa Milne Sophie Rose

Artlines | 3-2018 |

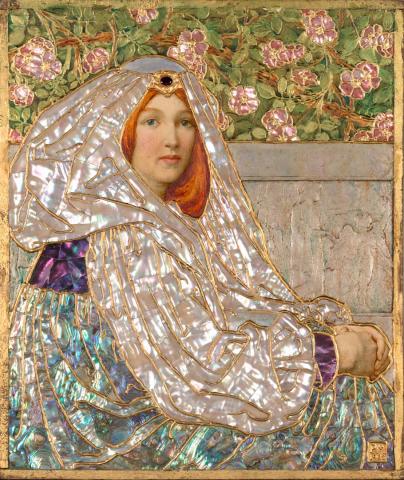

The 2018 'Of Women' display at QAG explores the female figure throughout nearly 500 years of art history.1 The women in these works present different visions of femininity, and their costumes and pose denote wealth, status and national identity. But they are also objects of our gaze and the act of looking at them is an act of interpretation.

For centuries, artists have been captivated by the female form. From the exaggerated bodies of Neolithic fertility figurines to Renaissance heroines, the female body is a constant thread in the history of art. The works in ‘Of Women’, drawn from the Gallery’s painting and print holdings, span nearly 500 years and take an interesting view of the history of the female figure in art. In daily life, people select clothing and accessories to act out a particular role or version of themselves. The women in these portraits are no different: to those who observe, their costumes are chosen to signify their wealth and status, national identity, or even their mythical alter egos.

With this in mind, we are prompted to ask: who is being looked at, and by whom? In 1972, art historian John Berger wrote on the subject: ‘One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.’2 Elegant and finely rendered, the women in this display are nonetheless objects of our gaze. ‘Of Women’ celebrates these figures while offering a critical lens on how they are depicted and who has depicted them. In this article, we have considered the work of two artists ― Angelica Kauffmann and George Romney ― who present a theatrical vision of femininity. Adopting costume and props of the stage, these images offer heightened, yet distinct, views of women.

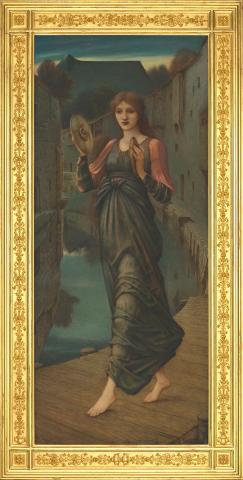

Of the paintings displayed in ‘Of Women’, only one was created by a woman — The deserted Costanza c.1783–84 by Swiss artist Angelica Kauffmann. Kauffmann is among the few female masters whose name and works have made their mark in European art history. Trained by her father from an early age, she was one of two female founding members of the Royal Academy London in 1768. She lived in a number of major European art centres, including Milan, Florence, Rome, Venice and finally London, where she was admired for her great talent, particularly in portraiture.

The deserted Costanza illustrates the opening scene from Pietro Metastasio’s eighteenth-century libretto for Joseph Haydn’s operetta, L’isola disabitata. In the painting, we see the soprano, Costanza, overcome with grief after discovering her husband has abandoned her. Indeed, Kauffmann’s painting adopts the operatic drama of its source text. Constanza’s body appears limp and heavy; her eyes roll back dramatically, looking far beyond the frame. Arms outstretched, she carves her testimony on a rock with a broken sword.

Kauffman’s image is undeniably theatrical, and perhaps borders on the rhetoric of female ‘hysteria’. However, rather than a realistic portrait of womanhood, the painting is an exercise in performance. Through props, costume and gesture, the female figure performs her role as grieving wife. In this light, we can see the scene as a knowing act: the soprano plays out her sorrow and her gender to heightened extremes.

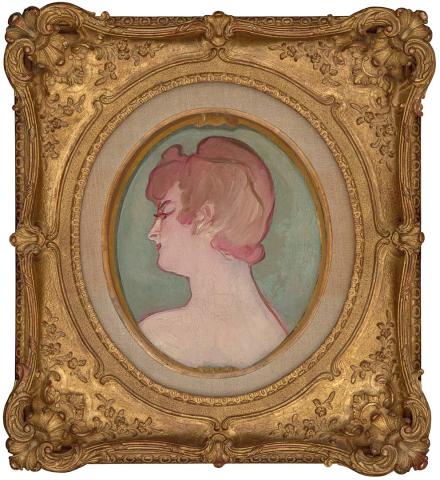

George Romney wields theatricality to a different effect in his neoclassical rendering Mrs Yates as the Tragic Muse, Melpomene 1771. This portrait, commissioned by the leading tragedienne of the day, Mary Ann Yates (1728–87), eschews the high drama of Kauffmann’s Costanza for a pale, austere depiction of a mythological muse. Mrs Yates was a successful figure in Georgian theatre who was nearly 20 years into her acting career at the time of this portrait. She was well known for her roles as Shakespearian heroines, but here she adopts the guise of the Greek Muse of Tragedy, Melpomene. Shown in three-quarter profile, Mrs Yates' gaze is fixed beyond her audience as she clasps a small dagger (one of Melpomene’s attributes) in her right hand. She is both resplendent and calm in her neoclassical garb, apparently in control of her role as she adopts the contrapposto pose of a classical sculpture rather than the fluid, emotional gesture one might expect from an actress.

Romney was one of the most successful portraitists of the late eighteenth-century, and his work is found in significant collections across the globe. His sitters, who were predominantly female, were often leading social figures including several actresses. While both Kauffmann’s evocation of Costanza and Romney’s portrait of Mrs Yates depict dramatisations of a fanciful character, the latter contains a second layer. Mrs Yates not only plays the role of mythic muse but also performs herself. In Romney’s portrait, she enacts a stately, almost ethereal, version of herself, far removed from the frivolous reputation of actresses in the eighteenth century.

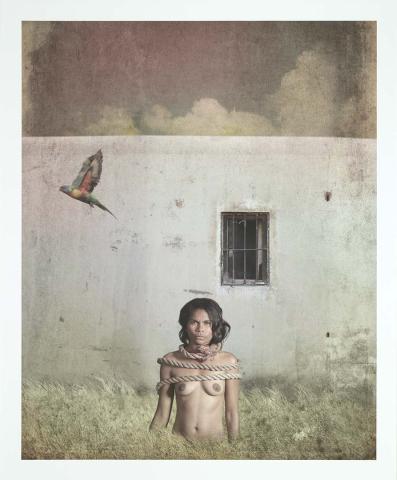

‘Of Women’ spans half a century of image-making, ranging from Cornelius Jannssen van Ceulen’s Portrait of a lady c.1640 ― whose finery denotes her social standing ― to a recently donated suite of contemporary photography by Bidjara artist, Michael Cook, Broken Dreams 2010, in which an Indigenous protagonist adopts the garb and posture of the British colonialists. With each figure depicted across this timeframe, Berger’s statement still rings true. These women are aware of being looked at, and the act of looking at them is also an act of interpretation.

Endnotes

- 'Of Women', International Collection display, Queensland Art Gallery, 2018.

- John Berger and Michael Dibb, Ways of Seeing, Penguin: London, 1972, p.47.

Connected objects

Broken Dreams #1 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #2 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #3 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #4 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #5 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #6 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #7 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #8 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #9 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

Broken Dreams #10 2010

- COOK, Michael - Creator

La Belle Hollandaise 1905

- PICASSO, Pablo - Creator

The mystic wood c.1910

- WATERHOUSE, J.W. - Creator

Aurora 1896

- BURNE-JONES, Edward - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject