Collection focus: Enduring ideas and innovators of Asian art

By Tarun Nagesh

Artlines | 3-2015 | June 2015

Drawn from the Collection’s historical, modern and contemporary Asian holdings, a new display in QAG’s Gallery 6 [2015] represents some of the key ideas in the art history of Asia, writes Tarun Nagesh.

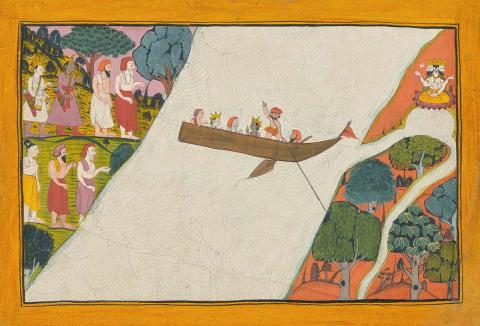

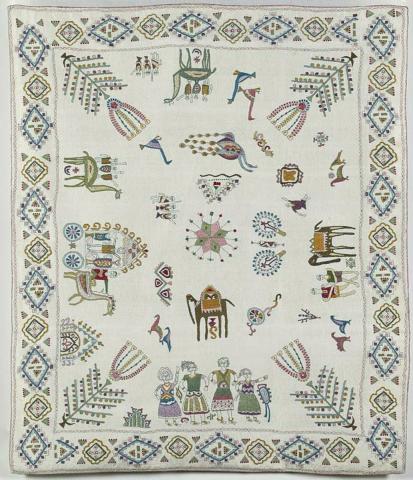

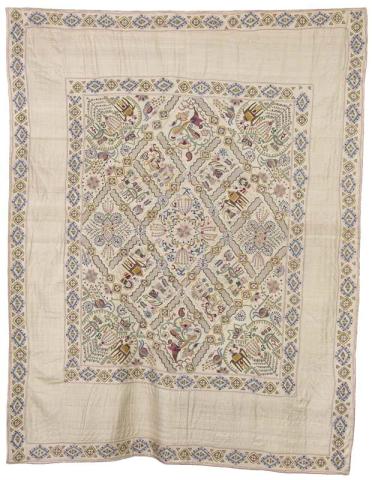

Subjects and approaches that have remained influential for centuries are the focus of a new display of Asian art at the Queensland Art Gallery. Featured are early examples of subjects and approaches that have remained influential for centuries. These include works that highlight the enduring prominence of miniature painting in South Asia and ink painting in East Asia, textiles that show how old techniques are employed as a narrative device, and an ancient Gandharan Buddha, which tells of a long history of figuration in the region

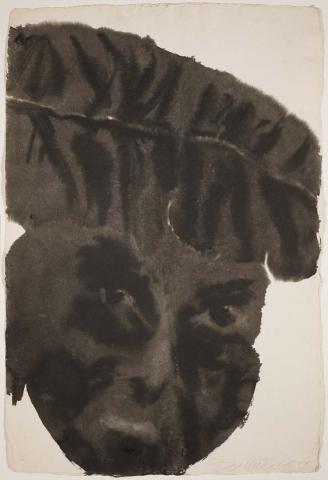

The Gallery holds important works by some of the pioneering figures of contemporary art across Asia. Indonesian artist Affandi is a household name in Asian Modernism, and his painting Self portrait in Kusamba Beach 1983 captures his expressive style, while Aung Myint is one of the pioneers of experimental art in Myanmar, and Tang Da Wu is a leader in establishing contemporary art in Singapore. Their deconstructed and unique approaches to portraiture signal why these artists became such influential figures in South-East Asia.

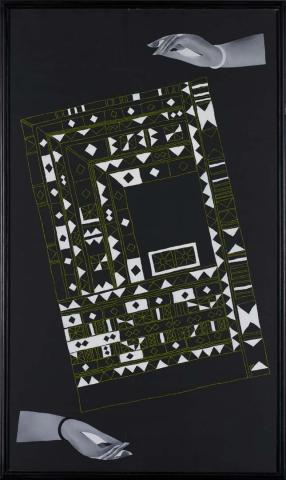

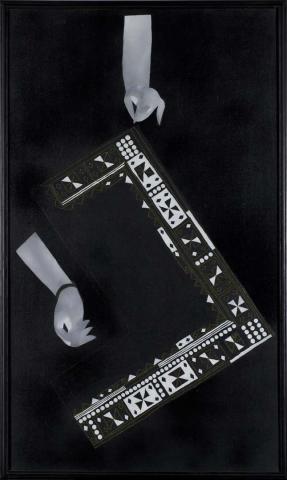

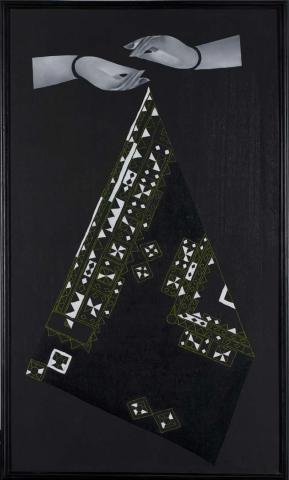

Vietnamese artist Dang Thi Khue persevered through tumultuous societal changes in her homeland, working for the Communist Party before emerging as a leading figure in the new artistic freedom of the 1980s. Her triptych from 1995 poetically marries motifs of Buddhist mudra with geometric designs that reference Vietnamese textile designs, and this delicate work is placed in conversation with examples of Buddhist art and contemporary textiles.

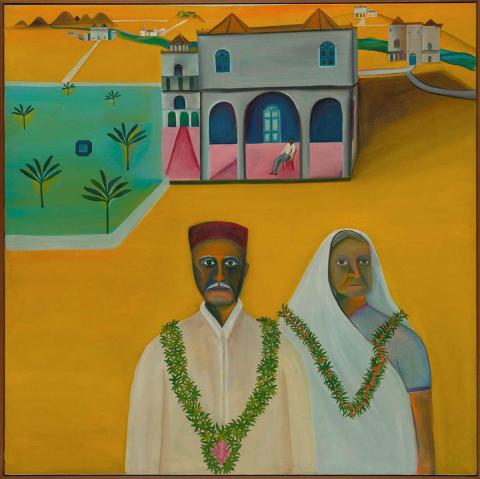

Various forms of miniature painting are showcased with recent acquisitions that illustrate the Hindu epic of the Ramayana, as well as the experimental styles of Pakistani artists Saira Wasim and Nusra Latif Qureshi. The vivid flat colours and variation in scale and perspective in Bhupen Khakhar’s Portraits of my mother and my father going to Yatra also reference the Indian miniature tradition. This is an early work by Khakhar, who was one of the first artists to break away from India’s institutionalised modernism. He achieved widespread international recognition and was written into the Salman Rushdie novel as the accountant (a previous occupation of Khakhar’s) in the 1995 novel The Moor’s Last Sigh. Khakhar returned the favour by painting Rushdie’s portrait as The Moor, now held in London’s National Portrait Gallery.

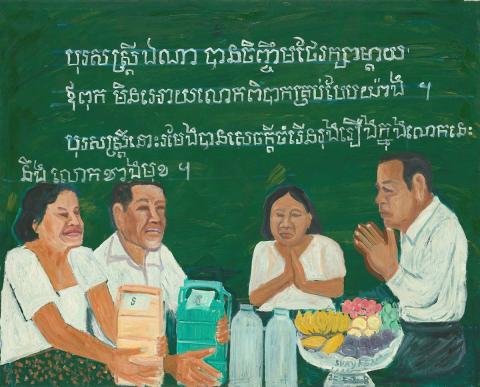

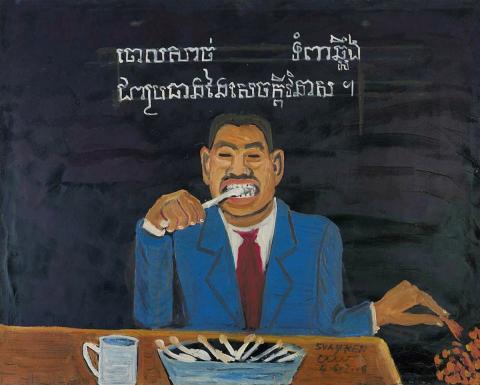

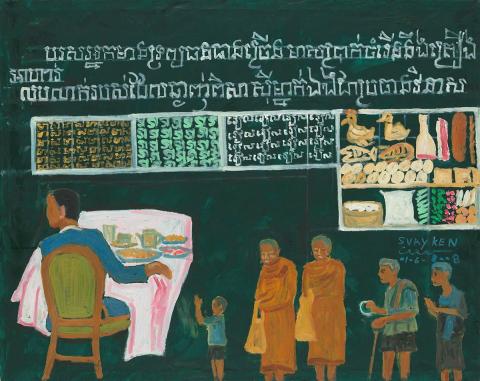

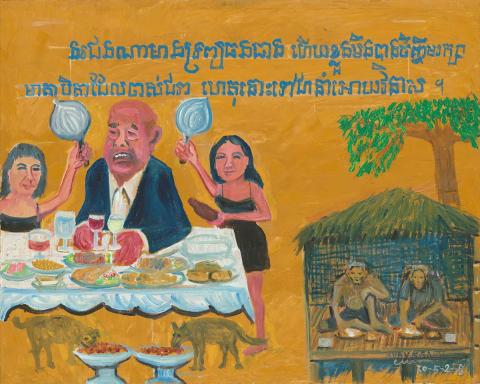

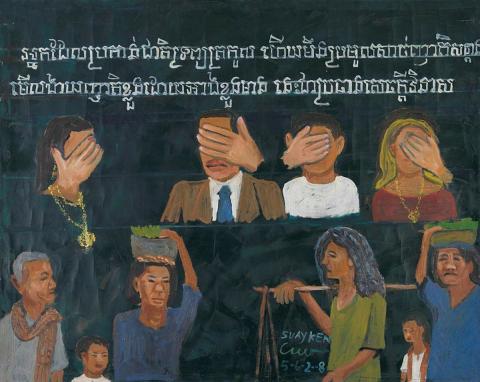

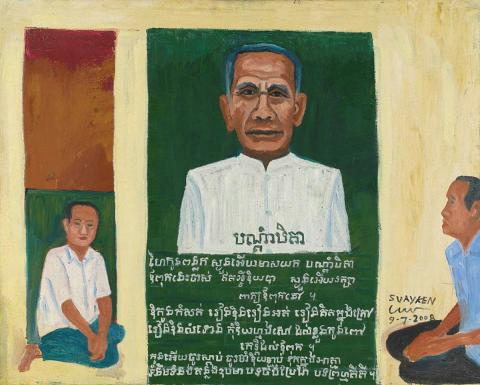

Cambodian artist Svay Ken’s ‘Sharing knowledge’ series was the last major series the artist painted. Within these allegorical paintings are social lessons and moral observations, drawn from the life experiences of providing a man who worked in a hotel in Phnom Penh before being sent to the country for agrarian labour during the Khmer Rouge regime (1975–79), and returning to become one of the country’s most heralded painters of the contemporary era.

Similarly, social upheavals are explored by Chinese artists who draw on rich symbolic imagery to subtly critique the governmental regime in the wake of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). Huang Yongyu’s expressive paintings continue a tradition of depicting natural subjects, such as birds and lotus, with the calligraphic brushstrokes of the Chinese ink-painting genre. His life and works reflect of the heavy restrictions artists in China faced at this time. Persecuted because of the supposed subversive nature of his subjects, he was later exonerated and celebrated after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. Yu Youhan’s colourful Flower bicycle 1989 is another important work, created immediately after the Tiananmen Square massacre in June that year. It satirically reads: ‘When I’m riding my flowery bicycle, the future looks rosy’.

Displayed around one of the Collection’s most popular sculptures, Bharti Kher’s The skin speaks a language not its own 2006, this suite of works presents a diverse range of artistic practices that have become influential across Asia.

Author: Tarun Nagesh, Curatorial Manager, Asian and Pacific Art, QAGOMA.

Source: Artlines 3-2015, pp.12–13.

Connected objects

Amazing 2012

- Aung Myint - Creator

Buddha 2nd-3rd century CE

- UNKNOWN - Creator

Bust of the Buddha c.15th century

- UNKNOWN - Creator

Self portrait in Kusamba Beach 1983

- AFFANDI - Creator

Flowery bicycle 1989

- YU Youhan - Creator

Lotus with birds 1984

- HUANG Yongyu - Creator

Wo yu (Kneeling fish) 1986

- GUAN Wei - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject