Ever Present: Photographs from the Collection 1850–1975

By Sally Foster

‘Ever Present’ June 2013

The invention, in 1839, of photography — which revealed that an image could be made by light alone and fixed to paper or glass - irreversibly changed how the world was perceived and recorded. Within a decade of William Henry Fox Talbot’s (1800–77) and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s (1787–1851) almost simultaneous announcements of their discoveries, photographic processes capable of producing a crystal clear `window on the world` spread ubiquitously, revolutionising the modern era.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the far-reaching implications for art were only just being realised. During the first half of the twentieth century, photographers grappled with the medium’s artistic potential, attempting to establish it as a modern art form. Armed with ever smaller and faster cameras, photographers took to the streets to record, document and capture the modern world and, in doing so, developed an entirely new visual language.

'Ever Present' presents a broadly chronological history of photography from 1850 to 1975, drawn from the Queensland Art Gallery’s international art collections. Reflecting the somewhat arbitrary nature of photography’s beginnings, the exhibition presents works by unknown nineteenth-century photographers alongside iconic images of the twentieth century by renowned practitioners of pictorial, documentary, modernist and street photography. United primarily by their medium, these works suggest the multiple narratives that contribute to the history of photography in the pre-digital era.

Beginnings in portraiture

The most popular and abundant genre of early photography was portraiture. In the years immediately following the dissemination of the daguerreotype process in France in 1839, professional photographic portrait studios started appearing around the world. The earliest known studio opened in New York City in March 1840 and, by the late 1840s, daguerreotype studios were common throughout the United States and Europe. From the fragile and precious daguerreotype to inexpensive and widely available tintypes and cartes-de-visite paper photographs, portraiture was the most visible genre of the medium from the middle of the nineteenth century. The photographic portrait had a profound effect on the lives and recorded histories of ordinary people, such as the couple who appear here as ghostly subjects in a daguerreotype, identified only by a hand-written inscription on the case as ‘Mr and Mrs Caleb Morgan’. As with all of these portraits, nothing is known of this couple beyond this surviving photograph, but as it had become possible to capture an ‘exact likeness’ in life, they remain visible and present long after death.

Travel, landscape and architecture

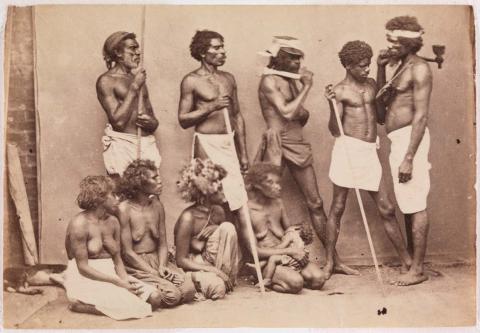

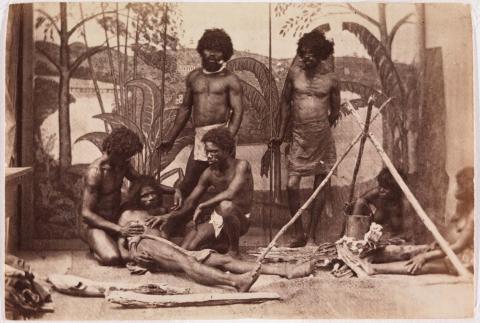

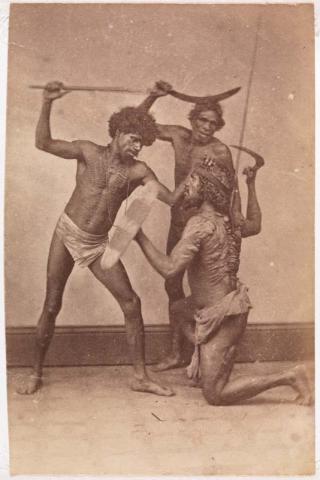

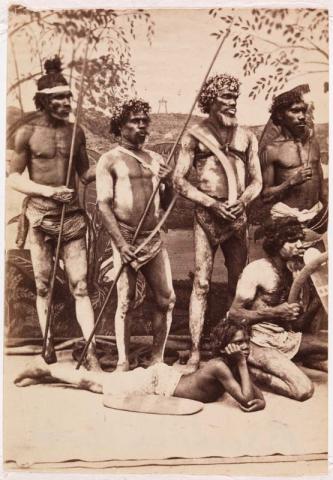

With the appearance of large yet portable cameras and the rapid development of photographic techniques in the mid-nineteenth century, professional and amateur photographers across Europe, North America, Asia and Australia took to travelling with the express purpose of photographing landscapes, architecture and people. The medium quickly became the most immediate means by which images and knowledge of diverse cultures and geographies were collected, succeeding earlier painted and printed views. However, as the scientific and documentary application of photography increased, photographs such as Daniel Marquis’s studio portraits of Indigenous groups, on display here, demonstrate that the empirical nature of the photograph was not inherently objective. Subjects could be romanticised or distorted in various ways, depending on the viewpoint of the photographer. Photography thus became a culturally inflected medium, used for a variety of public and private purposes. Playing an extraordinary role in the transformation of visual culture, photography has also had a significant impact on society, documenting and affecting social change as well as recording the progressive triumph of mechanisation and technology over nature.

Innovation and art

Photography’s invention brought with it an entirely new dimension to the visual arts. By the end of the nineteenth century, photography’s far-reaching implications for centuries of artistic tradition were only beginning to be realised. Photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron began to grapple with the artistic potential of the medium, attempting to bring it within the service of art by drawing on the history of European painting in works such as the ethereal Portrait of Frances St John c.1870, displayed here. At the same time, photographers saw the potential benefits that came with the ability to make multiple reproductions of an image from a single negative. Alfred Stieglitz reproduced photogravures from original negatives in his journal Camera Work, which was disseminated widely and exerted considerable influence on international trends in modern photography. Similarly, the pioneering development of the moving image steered photography away from the pictorial domain and the creation of unique objects — the traditional focus of artistic practice — and instead towards an ever-expanding future of increasingly realistic representations of the world.

Reportage and the modern world

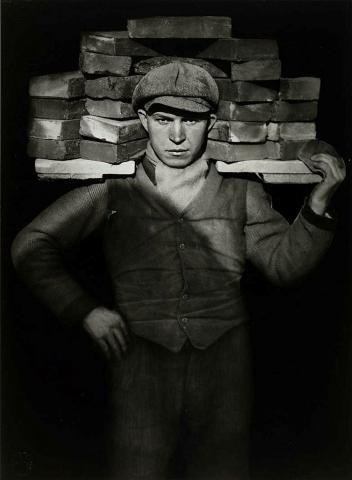

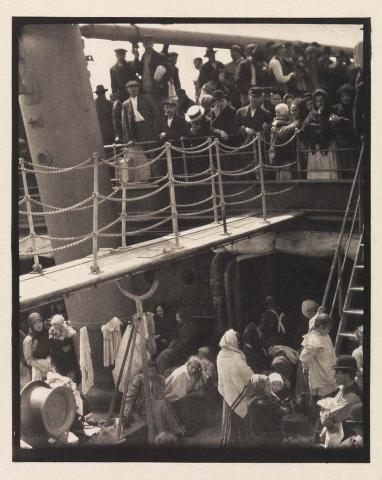

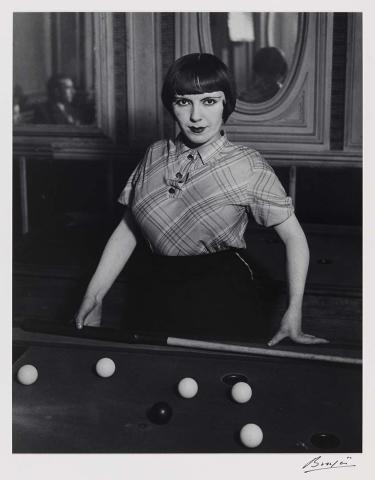

As the early years of the twentieth century unfolded, what came to define photography was not the capacity of the photographic image to emulate a painting, but its ability to capture, in a fraction of a second, what Henri Cartier-Bresson termed ‘the decisive moment’. Armed with ever smaller and faster cameras — such as the pocket-sized 35mm Leica, released in 1925 — photographers took to the streets to capture on film such fleeting, temporal moments as the one seen here in Cartier-Bresson’s Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, Paris 1932. This new approach profoundly influenced the development of photo-journalism, particularly through Magnum Photos, the agency Cartier-Bresson and fellow photo-journalist Robert Capa helped establish in 1947. At the same time, photographers as diverse as Brassaï, Walker Evans and August Sander created extensive archives that recorded with extraordinary detail everyday aspects of the modern world. The work of such artist-photographers therefore transected the previously separate worlds of documentary photography and fine art.

Style and form

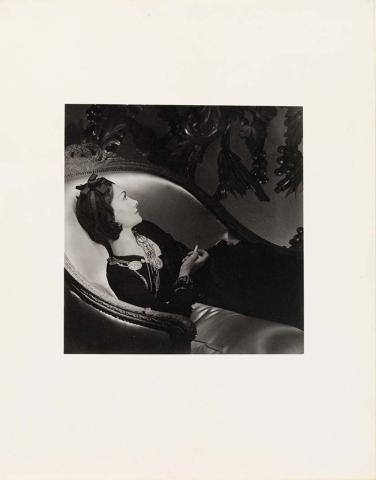

As a consequence of the accelerated tempo of life at the turn of the twentieth century, brought on by advancements in technology and mechanisation, the representation of time and motion through space became a preoccupation for artists. Realising that the camera gave them a unique viewpoint, photographers attempted to capture the new dynamic of modernity, literally expressed through images of people and objects travelling at speed through the modern world. Employing a multitude of perspectives, photographers such as Stan Berriman chose abstracted and highly stylised forms — such as in Star turn c.1940, displayed here — to evoke movement within an otherwise still image. Conversely, other photographers responded to the accelerated pace of life by attempting to slow it down, and even stop it altogether. Drawn to the objectification of life in the modern era, photographers such as Edward Weston, Horst P Horst and Max Dupain celebrated stillness, focusing their cameras on the formal properties of both animate and inanimate objects in an effort to evoke a sense of timelessness in their images.

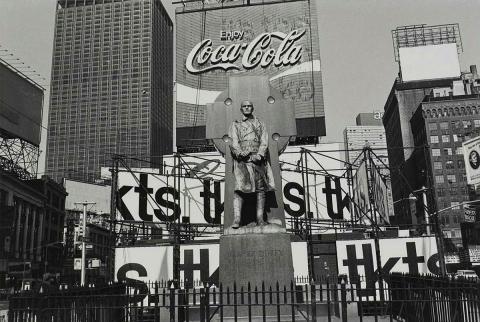

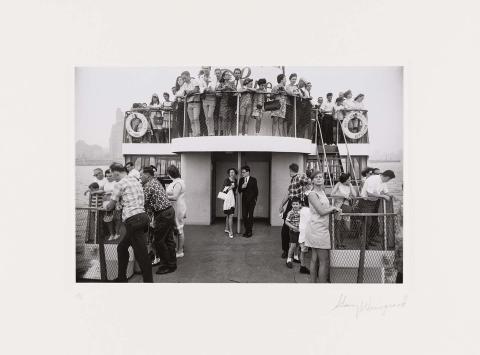

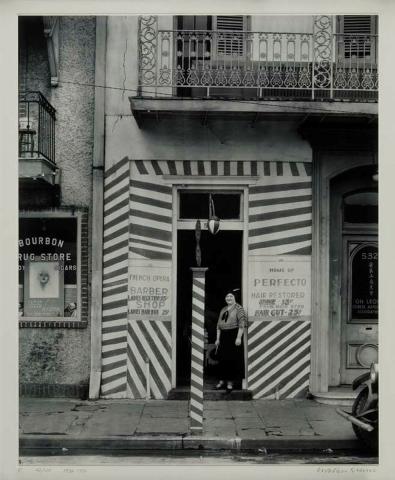

The streets

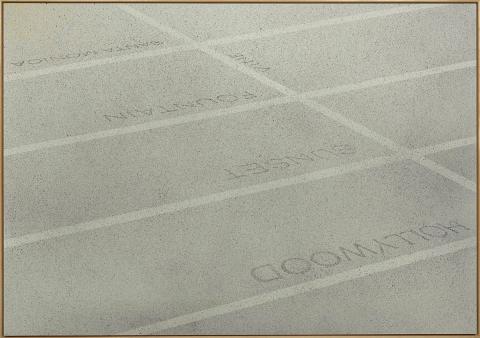

Since the late nineteenth century, photographers have documented the vibrant life of city streets around the world. From the 1940s, a particular style of street photography developed in New York. Lisette Model, Robert Frank and others drew on the tradition of documentary realism — in which photography was used to foreground social and political issues - to create a new style of street photography that critiqued contemporary American culture, albeit in a less didactic manner. Then, in the 1960s and 70s, artists like Diane Arbus increasingly liberated the genre from the idea that photography’s function was primarily documentary; instead, the focus shifted to one of increasing subjectivity, reflecting a complex understanding of identity — as in Arbus’s Patriotic young man with a flag, N.Y.C. 1967. For Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, the visual complexity of contemporary urban culture became the backdrop for an art that abandoned any appeal to universal principles and sentimentality; rather, their photography developed an aesthetic that embraced irony and was characterised by cool emotional detachment. Photography — now with a history of over 100 years of image-making — became fully integrated into the territory of art, utilised by artists like Ed Ruscha as simply another tool for the creation of images.

Connected objects

Athlete 1938

- DUPAIN, Max - Creator

Star turn c.1940s

- BERRIMAN, Stan - Creator

Mr and Mrs Caleb Morgan c.1850

- UNKNOWN - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject