Tsuyoshi Ozawa's 'Vegetable weapon' series

By Zoe Butt

A constant traveller whose work illustrates the beauty of sharing ideas through interaction, Tsuyoshi Ozawa's reputation as a conceptual artist is grounded in the essence of dialogue. His practice adapts traditional sensibilities to everyday life. Dissatisfied with the limited expression he felt through the medium of paint, Ozawa turned towards a growing practice within international contemporary art that focuses on dialogue, communication and exchange, as opposed to the revered status of an art object.

Ozawa embraces the potential of art to provide new meanings to cultural, social and political acts of contemporary life. The concept, and experience, of travel was an early turning point for Ozawa, who was delighted and stimulated by the process of communication and interaction between people. Drawing on the experience of travel and the various cultural rituals he encountered, Ozawa examines how we attach meaning to objects. Whether it is the conversion of a traditional Japanese milk box into a mini portable gallery, or the devising of a weapon of war made from the ingredients of local cuisine, Ozawa's practice humorously proposes new ways of thinking about assumed functions of objects, as well as their representative value and worth.

Ozawa graduated from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in 1989 where he was trained as a painter in the classical tradition. As a student in the late 1980s he observed the heady consumerism of Japan's economic boom and became highly critical of the moral and social values of Japanese society. The trend toward investment in commercial objects of little meaning or worth further aggravated Ozawa, who felt at odds with what he calls the many 'new paintings' that appeared in corporate-funded art events and buildings at this time.1 Ozawa struggled with the idea of art as a commodity and was disturbed by the urge for the new and transient. Surprised that anyone would want to buy his work, he felt a huge responsibility as an artist to provide something of value and worth in return. Acutely aware that the art scene was accessible to so few in relation to the majority of the population, Ozawa began to devise means by which his art would reach a broader audience.

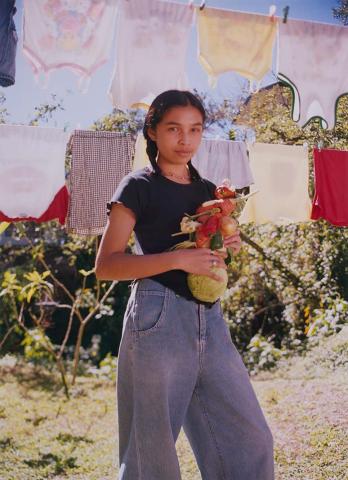

The 'Vegetable weapon' photographic series began in 2001 and has taken Ozawa around the world, continuing his experimentation with dialogue and exchange. In each city Ozawa visits, he invites women to cook their favourite meal. The essence of this project is grounded in the act of sharing a meal, a common and necessary part of human life. These vegetables and condiments are assembled into models of weapons and photographed with each participant, the ingredients providing the food for the party that follows. Each photograph is carefully framed with the weapon held poised as if ready to fire. In the 'Vegetable weapon' series it is women who hold these parodies of war: a deliberate and conscious decision by the artist to highlight assumptions of gender in contemporary conflict.

Ozawa's photographs display a variety of foods that are particular to different cultures or communities. The viewer is drawn to the title of each image: Chapsui/Baguio, The Philippines or Parippu (Lentil curry) from Sri Lanka/New York. The inclusion of these descriptive titles is central to this body of work that seeks to challenge our placement of war and its instruments. Ozawa's vegetable weapons that are eaten and shared suggest the power of communication and the need to be sensitive towards differing cultural values and beliefs. Ozawa has said: 'Arms exist for killing people. Though 'Vegetable weapon' cannot kill anyone... Which arms do you choose?'2

Endnote:

- Takashi Shinkawa, 'Tsuyoshi Ozawa: Interview', in A guidebook to Tsuyoshi Ozawa's world, Isshi Press, Tokyo, Japan, 2000, p.122.

- Tsuyoshi Ozawa, February 2005, Queensland Art Gallery Research Library artist files.