ESSAY: Women and reality: Yun Suk-nam’s Pink sofa

By Emily Gray

Artlines | 2-2021 | June 2021

South Korean feminist artist Yun Suk-nam’s alluring theatrical installation Pink sofa 1996 underwent conservation treatment in preparation for the 2021 Collection-based exhibition ‘Reality and Invention: Contemporary Asian Art’, held in GOMA's Marica Sourris and James C. Sourris AM Galleries (3.3 & 3.4). This early installation work is a comment on oppression of Korean women in a patriarchal society — it expresses painful personal memories and the artist’s fear of returning to domestic life.

Born in Manchuria, China, in 1939, Yun Suk-nam’s family moved to Korea in 1944. Yun was a housewife and mother before deciding to become an artist at the age of 40. Having studied calligraphy but without any formal art training, she began by painting her mother, finding inspiration in the working-class widow who had raised six children through difficult times. Yun’s burgeoning practice was set against a backdrop of political turmoil: mass demonstrations against an authoritarian rule modelled on Confucian ideologies culminated in anti-government protests and a widespread campaign for democracy in June 1987. Student-led protests and the Minjung (‘People’s’) art movement, which embraced Social Realism, were calling for political change. During this political period, Yun and fellow artists Kim Jin-sook and Kim In-soon formed the October Group; in 1986, they held what is considered the first feminist art exhibition in South Korea. Yun’s consistent discourse on women deprived of independence and living in a society with long-entrenched gender inequality earned her recognition as a leading figure in Korean feminist art. In the early 1990s, after studying in the United States, Yun turned her attention to sculpture and installation using found materials to continue her exploration into Korean women’s lives. Concurrently, her work was gaining greater recognition both in Korea and overseas.

For the 46th Venice Biennale in 1995, Yun presented an installation titled The story of mother 1995, which featured painted wooden sculptures and candles burning in the foreground. Her mother had been her subject and source of inspiration for over a decade, but this work marked a turning point in the artist’s career: it was the end of the story of her mother and the beginning of her exploration into self and women in history. Already recognised as a leading contemporary artist at home, Yun was participating in major exhibitions overseas, awarded the Lee Jung-Seop Art Award — the highest honour accorded to Korean artists — in 1996, started IF magazine in 1997, and in the same year, was appointed the director of the Feminist Artist Network.

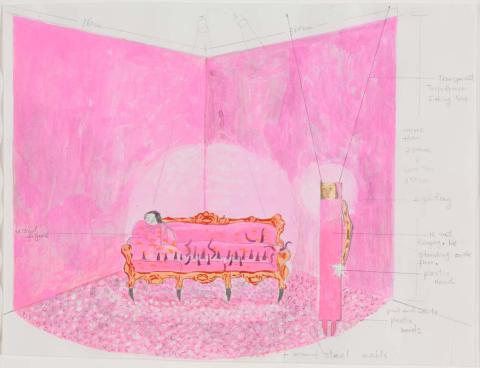

In the early 1990s, Yun used second-hand chairs in her work to personify women. Soon after, she embarked on the ‘Pink Room’ series — an exploration of maternity, in which she reflected her own story as a middle-aged, middle-class housewife and mother, and the painful memories of the oppression of women — and, by extension, their cross-generational social role — as non-participants in Korean society. In early 1996, Yun submitted Preparatory drawing for ‘Pink sofa’ to QAGOMA, which later served as a guide for its installation. The work was one of 144 artworks featured in the Gallery’s second ‘Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT2) and became an important addition to the Collection. It differs from the preparatory drawing in that the standing figure, made from recycled timber and situated on the periphery, was reworked to take on a more ghost-like appearance: rather than being suspended, the woman, who is painted in acrylic wash, is planted in heavy metal ‘feet’, her arm and mannequin’s hand no longer part of the milieu. At the time, curator Soyeon Ahn surmised, ‘This brilliantly coloured work expresses women’s hopes and their desire to escape from a society that demoralises rather than accepts them’.1

Central to the installation is a mock baroque sofa — a symbol of European taste and affluence and a style popular in Korea at the time. Yun reupholstered the salvaged sofa in vibrant Korean silk: ‘“PINK” is an uncertainty of emotion, particularly of women, which stemmed from the feeling that they could exist nowhere in the world’.2 Yun remodelled the legs, which appear to balance precariously on large metal nails. The sinister supports were inspired by eunjangdo, small knives carried by women for self-defence during the Chosun dynasty era (1392–1910).3 The seat cushions are pierced by long metal spikes, rendering the furniture unusable by anyone other than the seated figure tucked in the corner: constructed from recycled timber, the figure wears hanbok (traditional Korean dress) painted and adorned with mother of pearl, suggesting a pre-modern era. The timeline is nevertheless disrupted by the modern figure, who is literally marginalised by a sea of plastic beads covering the floor. Both women are isolated.

Realised at a pivotal time in Yun’s career, and framed against South Korea’s women’s movement, Pink sofa is as relevant today as it was when conceptualised quarter of a century ago. This significant installation is a comment on a society’s deep-rooted gender inequalities and conveys a strong message of female oppression while paradoxically offering a sense of optimism.

Emily Gray is Assistant Registrar, QAGOMA.

Endnotes

- Soyeon Ahn, ‘Yun Suk-nam’ [essay] attached to Acquisition Proposal for Preparatory drawing for ‘Pink sofa’, dated 27 June 1997, QAGOMA Research Library, p.142.

- Yun Suk-nam, ‘Detailed provenance’ form, QAGOMA Research Library.

- Kim Sung-jung, ‘Baubles, bangles and beads: Interviews with four Korean women artists’, Art Asia Pacific, vol.3, no.3, 1996, p.66.

Connected objects

Pink sofa 1996

- YUN Suk-nam - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject