The oldest living stories: A conversation with Robert Bleakley

By Simon Elliott

Artlines | 3-2022 | September 2022

Editor: Stephanie Kennard

A selection of some 66 bark paintings, generously donated to the Gallery by Robert Bleakley, will be on display in the exhibition ‘Transitions: Historic and Contemporary Barks from the Collection’, at GOMA until April 2023. The works reveal the distinctive art being produced in northern Australia in the 1950s and 60s — a critical period in the emergence of Aboriginal art in the public domain. Simon Elliott recently spoke with Robert about the works and what inspired his collecting.

While in his 20s, Robert Bleakley’s career took him to Sotheby’s London. From there, his journey with this unique art practice not only brought him home to Australia but also inspired decades of careful collecting — a collection he recently donated to the Gallery.

Simon Elliott: Robert, you were born in Sydney but found yourself at Sotheby’s headquarters in London, as the director of the newly formed tribal art department, at only 28 years old. That’s an amazing achievement in itself, but was that when you became interested in Aboriginal Australian bark paintings?

Robert Bleakley: Well, of course I had seen barks as a young person at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and later became deeply engaged in the tribal art market in London in the 1970s, but I found that bark paintings within the international tribal market were treated much like folk art and not really accorded any significance. They were seen as a sort of a later expression of Aboriginal culture — something that was directed towards the European audience because they were promoted by the missions that were here in colonial times. In the 1970s, collectors were predominately interested in African, Native American, Pre-Columbian and Polynesian works, some Oceanic, but nothing much more.

So that kind of dampened my enthusiasm for a long time. But I reacquainted my interest in bark paintings when I came back to Australia in 1983 and set up Sotheby’s here. I decided to host at least one Aboriginal art-focused auction a year with barks included, but it was a tough slog, I can tell you! There was a turning point in the market in the 1990s when it took off, and of course, the major focus of attention was on the Western Desert paintings. But even then, the bark paintings were always considered like a poor cousin in terms of the artistic merits and the interest they elicited within the collecting market.

This situation has continued until the last two years, really, where people have suddenly alighted upon more contemporary bark painters, works by Kunwinjku artist John Mawurndjul being the leading example in terms of market acceptance. Plus, the interest in paintings on canvas carried into the associated market of bark paintings. People began to ask, ‘Where do these paintings come from?’, ‘Where are the images derived from?’ And I said, ‘Oh, they’re from bark paintings’, as a shorthand response to a much more complex story,1 but that kind of generated an interest.

Out of this group you have so lovingly amassed and curated over 30 years, you must have some favourites. Can you share a few insights into them with us?

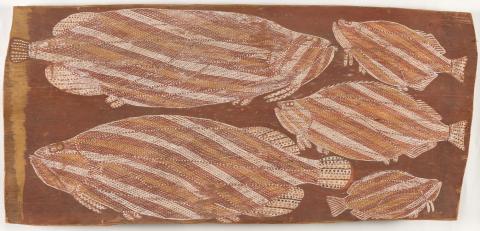

There are several which I had always planned to hold forever. One of them was a 1950s Groote Eylandt bark of dolphins, tortoises and the Seven Sisters, which might be a creation story or indeed a night-time reflection of the sky in the water, teeming with life. I just think it’s such a fabulous work.

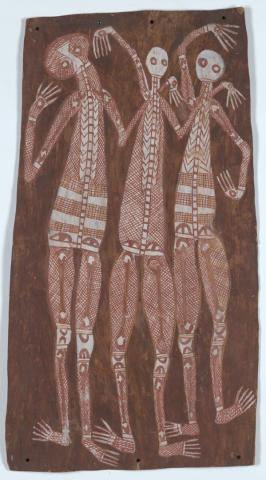

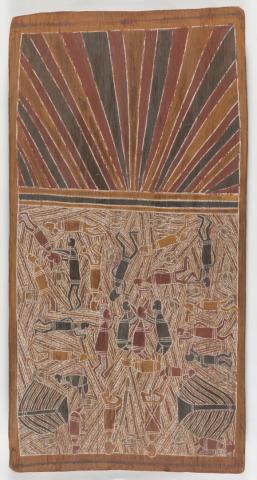

But the two that are particularly interesting to me are Kunwinjku artist Yirrwala’s undated Lorrkon ceremony dance of skeletons of three dancing Mimi spirits, which is a staggering work, and Rirratjingu Miliwurrwurr Dhangu artist Mathaman Marika’s Untitled (Buralku – spirit place for the dead) c.1960. The painting depicts part of the mortuary ceremonies of the Rirratjingu clan of north-east Arnhem Land. In the top left corner of the bottom panel, the spirit of the deceased, who appears with horn-like ears, is guided by three mokuy spirits to meet clan members who had previously died. The horned spirit appears again at the centre of the panel, being prepared for its journey to the land of dead. Two ancestors play didjeridu and clap sticks, to which women dance in mourning. Two banyan trees appear in the lower corners. In the top panel, rays of light from the setting sun — a metaphor for one’s passing from life to the afterlife — are coloured by the dust kicked up by the dancers’ movements. I find this bark very, very engaging.

There is one in particular, by an unrecorded artist, titled Mimihs hunting echidna: it was almost certainly part of a bark shelter from the wet season, as it’s got the spinifex gum on the right-hand side. So, it’s something produced with no intention of being sold or presented to a market. The same is true of Crocodile and water plant, which is also a western Arnhem Land bark, and is entirely consistent with the traditional motifs of rock art; I suppose both were to operate in ceremony for propitious outcomes for the hunt. Perhaps lastly, Tiwi master painter Deaf Tommy Mungatopi’s All-bin-mix-up of 1957 is astonishing with all its geometrical, conjoined squares and dots. He is one of the best painters and, consequently, was frequently commissioned to paint tutini (Pukamani burial poles) for the funerals of important people. Tiwi artists rarely describe the meanings of the non-figurative patterns and designs in their paintings in any great depth. All-bin-mix-up, however, is rich in interpretative layering: the red and black lines refer to the pattern of the artist’s blanket; the short white strokes to the rungs of a ‘whitefellow’ ladder used to collect wild honey or sugar-bag from tree tops; the white dots represent bush apples and the yellow dots bush plums; and the short white verticals in the lower register of the painting depict trepang (sea cucumbers) associated with the South-Asian Macassans, who fished off the Tiwi Islands until the beginning of the twentieth century. I bought it some 15 years ago and I remember it took my breath when I first saw it. And I paid a small fortune to own it!

Can you define what is so distinctive about bark painting that has kept you collecting them over the decades?

I’m drawn to these barks because of their encoded visual language. Most are made for Aboriginal people to see, less so for outsiders. They contain so many different elements that could be read as topographical narratives, or narratives linked to ceremony, which I find so compelling, and which give us a glimpse into a visual representation of the world’s oldest continual culture. For me, they are immensely important and, in time, I’m sure they will be put on the same level as the most important of the paintings on canvas from the Central Desert paintings of the post-pioneer Geoff Bardon period.

Thanks to QAGOMA, all these wonderous works now belong to a public collection. Despite their age, these bark paintings are living stories and yet they’re using imagery which has been evolved over tens of thousands of years. And there’s nothing else, there’s nothing that I know of that competes with that on the planet or, for me, can deliver the same connection. I look forward to seeing my old friends hanging on your walls — often!

Simon Elliott spoke with Robert Bleakley in June 2022. Selected bark paintings from Robert’s recent gift to the Gallery can be viewed in ‘Transitions: Historic and Contemporary Barks from the Collection 1948–2021’, at GOMA until April 2023.

Endnote

- Robert adds: ‘It would be more accurate to identify the images on barks as sharing source inspiration with works on canvas, body painting being one prime example. Many of the early boards drew inspiration from sand constructions, with the same elements used, but they are geographically and culturally removed from the Arnhem Land and Kimberley cultures from which barks largely derive’.

Connected objects

Mimihs hunting echidna c.1960s

- UNKNOWN - Creator

Crocodile and water plant c.1950s

- UNKNOWN - Creator

All-bin-mix-up c.1957

- MUNGATOPI, Deaf Tommy - Creator