Abdul Abdullah | Artist

By Bronwyn Mitchell

Artlines | 4-2020 | December 2020

Perth-born multidisciplinary artist Abdul Abdullah started as a painter before expanding his practice to include other media, writes Bronwyn Mitchell. In February 2021, Abdullah invites us to learn more about his practice in Open Studio.

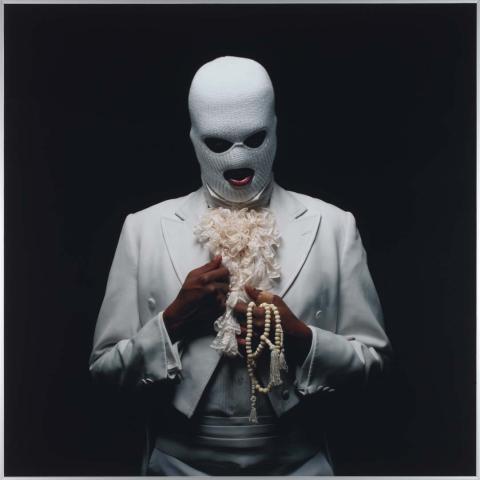

Abdul Abdullah is an artist on the periphery — an ‘outsider among outsiders’ — whose works explore themes of marginalisation and often find an audience in ‘those who perceive themselves as outsiders in some way’. He identifies as Muslim and his mother is from Malaysia (although, going back several generations, the family traces their roots to the Indonesian island of Sulawesi). He also has convict/settler Australian heritage on his father’s side.

Before becoming an artist, Abdullah was on a different career trajectory, completing most of a journalism degree before enrolling in an art subject as an elective — a decision that led to his studying visual art at Curtin University of Technology. The genesis of many of his works comes from reading or watching news, and he says that he conducts research for an artwork much like a journalist does for a story. But he is also interested in questions of moral philosophy and examining the systems and structures of power. ‘I don’t necessarily think about [my works] as statements, even though some of them are text, but rather as a contribution to an ongoing conversation’, he says. ‘So much of my work comes down to questioning tradition and the inherent biases people have and take for granted — traditions that people don’t question because they think this is just the way it is and the way it’s always been, without seeing how damaging or dysfunctional [those biases] are for people who aren’t rewarded by these systems.’ Unsurprisingly, Abdullah’s work attracts a certain amount of criticism, particularly from the conservative and religious right. He says he often feels compelled to explain and defend his work more than other artists are required to, but overall, he’s unperturbed: ‘I don’t think really there’s anything that contentious about what I do, but they will find contention in it’.

Now based in Sydney, Abdullah has a studio in an old office building due to be demolished in a year. He also maintains a studio in Yogyakarta. Prior to the changes brought about by COVID-19, he would visit several times a year to live and work amid the city’s vibrant art scene. ‘I did a residency through 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and then fell in love with the place and with the arts community there.’ His Indonesian studio is minimalist compared with his space in Sydney — ‘no running hot water, no shower, no frills’ — but he values the opportunity to make art and spend time among a community of artists whose visual aesthetics have been hugely influential to his own development, particularly Hahan (Uji Handoko Eko Saputro) and Eko Nugroho, whose works are both in the Gallery’s Collection.

One of the biggest influences on Abdullah’s practice was meeting fellow Australian artists Richard Bell and Vernon Ah Kee, ‘who are passionate, forthright and outspoken about what they believe in, and doing it with such integrity. Until I came across their practices, I didn’t know how to be an artist,’ he says, adding that he was inspired by their ability to make work ‘that’s political but not in any way dumbed down . . . they’re speaking their mind clearly and with authority’. A favourite Collection work — which will be on display as part of his curated selection for Open Studio — is Tracey Moffatt’s 7-minute video work Other 2009, comprising fragments of Hollywood films that depict imagined first contact between European colonists and Indigenous inhabitants. Abdullah first encountered the work at the 2011 Singapore Biennial, where its international context resonated deeply with him. The representation of ‘the savage, monstrous Other from a Western perspective . . . made so much sense, globally’, he says. ‘It’s such a smart use of visual language . . . using these little moments to reveal a history of framing the Other.’

Abdullah speaks highly of the artists who mentored him through his early career, and paying it forward — by mentoring young and emerging artists — is important to him, adding that he feels ‘a great obligation to those that come after me and those who came before’. When he facilitates student workshops, he will often talk about the Straight Path, in reference to his Muslim faith, but also about what he refers to as ‘the wobbly path’: ‘It took me ages to get to art school . . . Nothing came quickly and there were a lot of setbacks, but those setbacks were good in the end . . . obstacles almost enrich that process’. It’s a difficult message to convey to students, however, when ‘everyone seems in a hurry to be really good at something’, he observes. ‘Kids go from freewheeling artists, when they’re nine or ten, to perfectionists. In high school they shift . . . to thinking they’re not good enough. I encourage [them] to wreck their stuff, or to keep going until [they] like it, and then just go a little bit past it . . . you’ve wrecked it, but that’s all right because you went somewhere good and you can do it again.’

In many ways, Abdul Abdullah’s entry for the 2020 Archibald Prize encapsulates his philosophy of not being precious about his work. In an explanation accompanying a short video on Instagram — in which he uses a can of black spray paint to completely obliterate the top half of what looks to be a finished self-portrait — he says: ‘It was important to me that this wasn’t just a design element. The act of defacing is integral to its purpose. It doesn’t matter how long it took to make the painting; what matters is my agency and my choice. Few things are so precious that there is no value in their interrogation — everything that is built can be rebuilt, and no tradition inherently oppressive is worth maintaining’.

The Gallery’s Open Studio project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Bronwyn Mitchell is Editor at the Queensland Museum. She spoke with the artist in September 2020. ‘Open Studio: Abdul Abdullah’ is at QAG from 13 February to 13 June 2021.

Feature image: Abdul Abdullah, Iyok Prayogo, Nanang Sholeh, Edwin Roseno, Edwin’s daughter Kemangi, and Codit Sukowati, at Abdullah’s Yogyakarta studio, July 2018 / Image courtesy: Abdul Abdullah

Connected objects

Other 2009

- MOFFATT, Tracey - Artist

- HILLBERG, Gary - Collaborating artist

Related artists

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject