Women in Modern Art

By Jacinta Giles

Artlines | 3-2024 | September 2024

This Collection-based display celebrates women artists who challenged the conventions of the prewar era to create artworks they believed better reflected the experience of modern life. Working in the second half of the twentieth century, they experimented with form and rejected the realistic depiction of subjects, preferring instead to explore the emotive possibilities of their materials.

Individually, these women artists developed distinct approaches to representing modern life in the mid-twentieth century, but their respective innovations contributed to the evolution of modern art — and quietly asserted the role of women as a creative force.

Elizabeth Frink

Prominent British sculptor Elisabeth Frink spent the early part of World War Two in Suffolk, where she witnessed aircraft returning from war on fire, their twisted remains crashing into an otherwise peaceful countryside. It may have been this firsthand account of destruction that influenced the rugged, brutal and contorted surfaces of her work. Having shown an early interest in art, she studied at the Guildford School of Art, and later, at the Chelsea School of Art, in London. In 1952, during her time at Chelsea, she had her first real artistic success representing Great Britain at the Venice Biennale and having her sculpture Bird 1952 acquired by the Tate Gallery in the same year. Art critic Herbert Read described Frink’s practice at the time as ‘the most vital, the most brilliant and the most promising of the whole Biennale’.

Frink became part of a group of postwar British sculptors dubbed the ‘Geometry of Fear School’, whose tortured and battered-looking works expressed the anxieties and fears arising in the aftermath of the war. Best known for her stylised bronze sculptures, Frink’s subjects included the male figure, animals and religious motifs, drawing on archetypes of masculinity, struggle and aggression. The surface texture of her work Wild boar 1958 comes from working rapidly and forming wet plaster onto a metal armature. The plaster was then cast in bronze, preserving all the surface markings made by Frink’s hands and tools. The artist described her sculptures as being ‘about what a human being or an animal feels like, not necessarily what they look like’. Wild boar captures both the animal’s extraordinary physicality and Frink’s emotionally charged style.

Judy Cassab

When painter Judy Cassab migrated to Australia in 1951, to escape the immense suffering she had endured in Nazi-occupied Europe, she had already studied art in Budapest and Prague. At the National Art School in Sydney, she studied under prominent artists such as Grace Cossington Smith and Ralph Balson, and enjoyed a successful career, in Australia and internationally, and won many accolades throughout her career — including, on two occasions, the Archibald Prize.

Soon after her arrival in Sydney, Cassab found a teacher in the Hungarian painter Desiderius Orban, whose work reflected the influences of Cubism and the French post-impressionist painter Paul Cézanne. Orban told Cassab, ‘You are talented, but you stopped somewhere in Impressionism. You must forget that the table has four legs; use only what is essential to your picture. Forget the object’. Her teacher challenged her to give up being ‘the artist’ for six months and to paint only abstracts so that she could ‘feel’ her paintings again.

Although highly regarded as a portraitist, Cassab continued to work with abstraction throughout her career, stating:

I am an adventurer. Once I have an idea that I have worked on for three or four years, I get tired of it and I want to experiment. I consider the material as a vehicle that takes you into the unknown.1

Figures in Blue demonstrates Cassab’s desire to challenge the narrative approach of her early European training and reflects her commitment to exploring how form, colour and technique could, in her own words, ‘catch the likeness’ of the world around her.

Barbara Hepworth

British sculptor Barbara Hepworth is considered one of the leading artists of her generation. Her early interest in art led her to attend the Leeds School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London. It was during this time that she became exposed to avant-garde art tendencies, which had a significant influence on her artistic development. Hepworth used wood, stone and bronze to create sculptures that emphasise the interplay between mass and space. Her work was also heavily influenced by a deep connection to nature and the landscape.

Hepworth developed Orpheus as a response to her travels through Greece a few years earlier. As an ancient Greek story of a mythical poet who could pacify wild beasts when playing his lyre, there is a clear link between Orpheus’s musical instrument and Hepworth’s brass-stringed sculpture.

In 1956, the year she created Orpheus, Hepworth moved from working with blocks of wood and stone to the process of cutting shapes from sheets of metal, which allowed her to describe the enclosure of space in new ways. This method also had the advantage of being easily scaled up so that she could create much larger works with the support of her assistants. Orpheus is one of several small maquettes that the artist made in preparation for the commission Theme on Electronics (Orpheus) 1956, which stands over a metre high.

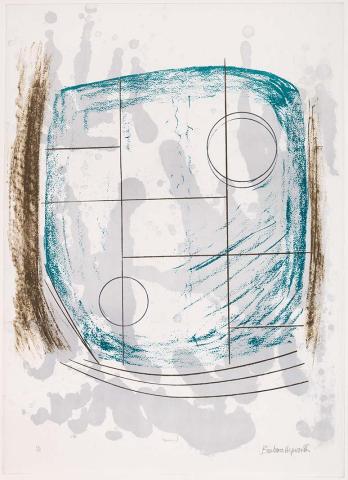

Hepworth’s prints are arguably the least well-known aspect of her practice yet are best appreciated in dialogue with her sculptures. Hepworth arrived at printmaking relatively late in life, when Stanley Jones of Curwen Press established printmaking facilities in a studio in St Ives, Cornwall, where Hepworth lived. She made several portfolios between 1969 and 1971 using screenprinting and lithography techniques. Printmaking allowed her to work on ideas that she would eventually translate into sculptures, as the abstract concepts of space, form and texture could be explored through transparent layers and bold mark-making.

The ‘Aegean suite’ is a continuation of Hepworth’s fascination with Greece, which stemmed from her visit in 1954. Several of the lithographs from this suite make links between geometric forms and sites associated with ancient Greek culture. Like many of Hepworth’s other works on paper, Cool moon explores

her interest in celestial subject matter. The ‘Aegean suite’ was the last portfolio of prints that the artist made, although she continued to produce individual lithographs and screenprints in the final years of her life.

Inge King

Born in Berlin in 1915, sculptor Inge King escaped Nazi Germany in 1939, settling first in London and then in Glasgow. During this time, she received formal art training at the Berlin Academy, the Royal Academy Schools in London, and the Glasgow School of Arts. She emigrated to Australia in 1951, making Melbourne her home. As soon as she arrived in Australia, King was at the forefront of the development of abstract sculpture, both through her own practice and as a founding member of the Centre Five group, whose mission was to foster greater public awareness of contemporary sculpture.

Believing that ‘sculpture is the exploration of form and space — it is drawing from a thousand different angles’, King experimented with figuration, then Cubism and organic abstraction. During her 70-year career, she was acclaimed for her innovative style of abstraction that obliquely referenced various

subjects, such as animals, plants and the trajectories of planets. In the year Sculptural form was created, King began to experiment with aluminium, believing that affordable and easily accessible metals should be used in the creation of contemporary sculpture. It was also during this time that the artist played

with symbolic references to organic forms — such as animals, bones, shells and plants — to make sense of her surroundings in a new country.

From the 1970s, King began to focus on creating monumental public artworks, for which she would first develop small maquettes, both to test the work’s feasibility and to attract commissions. Her work also evolved from heavily textured and overtly expressive forms to simpler shapes with refined surface treatments, as can be seen in Sculpture maquette, with its elliptical shape and smooth, black-painted surface. It was also during this time that King made the decision to stop drawing models of her sculptures altogether, believing that the three-dimensional maquettes were more important to her creative process:

Just because I make a maquette, it doesn’t mean it will be enlarged . . . I used to draw my sculptures but then I felt it inhibited me, so I stopped drawing . . . you have to work in the round, so I have to plan for it in a three-dimensional way . . .2

Sculpture maquette was gifted to the Gallery from the Queensland Department of Works. Originally commissioned by the department as a potential public sculpture for the new Courts of Law building, which opened in Brisbane in 1981, King’s sculpture was never realised at the scale she intended.

Endnotes

- Judy Cassab in ‘James Gleeson interviews: Judy Cassab’, 1 January 1978, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, https://nga.gov.au/media/dd/documents/cassab.pdf accessed July 2024.

- Inge King, quoted in ‘Inge King: Constellation’ [exhibition text], 2014, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, see https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Inge-King-Constellation_Large-print-labels.pdf accessed July 2024.

Connected objects

Orpheus 1956

- HEPWORTH, Barbara - Creator

Sculptural form 1958

- KING, Inge - Creator

Sculpture maquette 1980

- KING, Inge - Creator

Figures in Blue 1965

- CASSAB, Judy - Creator

Wild boar 1958

- FRINK, Elisabeth - Creator

Related artists

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject