Wang Qingsong was born in Hubei Province, China in 1966 and graduated from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, Sichuan in 1991. Wang Qingsong's work is indicative of, and reacts to, rapidly changing trends that are dramatically affecting aspects of contemporary Chinese culture. He comments on the abundance of consumer merchandise and multinational company imagery that has successfully flooded the Chinese market. Aspects of capitalist understandings of 'progress' that mark this phenomenon are epitomised in the popular official Chinese slogan quoted by the artist: 'One change a year, one big change in three years, and one unidentifiable transformation in five years'.(1) Wang Qingsong chooses to act as a social commentator on the apparent 'richness' of consumer culture in direct comparison to the extreme demands of a population of 1.2 billion people who have basic domestic needs unmet, highlighting the fundamental issue of the injustices of wealth distribution globally.

In 1999 Wang Qingsong gained notoriety as the new proponent of 'gaudy art', a term dubbed Chinese critic, Li Xianting, to express the garish appropriation of motifs from media and popular culture. Wang's ability to highlight the irony of China's burgeoning consumerism was typified by his work 1000-hand Soliciting Buddha 1999 in which a seated, seemingly meditative Buddha holds a Coca-Cola bottle as well as various brand name consumer items such as mobile phones and CDs. Chinese Communist leader Deng Xiaoping's introduction of free trade over the past two decades has been paralleled by an embracing of Western goods and popular culture. The juxtaposition of this consumerist imagery with Buddhist iconography suggests that changes in outward appearances and behaviour reflect changes in spiritual beliefs.

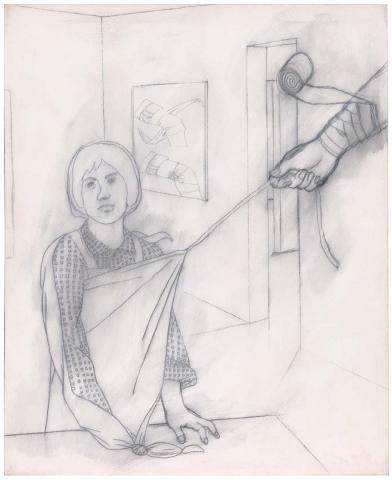

Wang Qingsong has expanded the tawdry and the profane, ideas so central to 'gaudy art', into another historically referenced dimension in this work, Night revels of Lao Li. This very large-format photographic work is a study in social commentary: it addresses the effects of modernisation in contemporary China.

Night revels of Lao Li depicts a contemporary figuration of the tenth century Tang dynasty scroll by Gu Gongzhong, Night banquet of Han Xizai. For this earlier work Emperor Li Yu ordered his court painter, Gu Gongzhong, to attend the lurid, indulgent parties of his Internal Secretary, Han Xizai. Emperor Li valued Han Xizai's talent as a statesman and so chose to overlook his excesses, but he regretted not being able to see such activities with his own eyes. Hence Gu Gongzhong was sent to infiltrate these events for evidence to support the Emperor's suspicions that Han Xizai intended to usurp his imperial power. Night banquet of Han Xizai is Gu Gongzhong's depiction of what he experienced - a night of erotic indulgence - and is a key work in the Imperial Palace Collection, Beijing.

In Night revels of Lao Li, Wang Qingsong depicts himself in the dual role of court painter and spy. 'Lao' is used as an esteemed title when addressing one's familiar senior, and here Wang Qingsong has placed his friend and art critic Li Xianting as the indulgent politician, the initiator of the erotic revelry. In keeping with the composition of the original work, female models were hired and dressed as prostitutes in kitsch and provocative attire, while tables were laden with contemporary brand-name consumables. He suggests that indulgent behaviour is as common a practice amongst high-ranking officials today as it was during the former dynastic rule of Emperor Li Yu. The 'consorts' appear to languish over 'officials' (Li Xianting) and other personalities in the contemporary Chinese art world, including the prominent curator of Chinese avant-garde art, Gu Zhenqing. By representing the Tang dynasty court officials as contemporary art scholars, Wang Qingsong deliberates on the analogies between historical and contemporary hierarchies and power structures. The photograph mirrors the multiple views of time that identify the continuous scroll format, but in a radically different way. Gu Gongzhong's traditional hand-scroll guarantees the viewer's intimate engagement with the work, given that the scroll would be unrolled to depict only one screen image at a time.(2) However, in Wang Qingsong's photograph, all screen divisions are simultaneously visible and the viewer's privacy has been abolished. The viewer gazes at the play of erotic indulgence, the only allusion to privacy being that the actors (all except the all-knowing Wang Qingsong, who in one view returns the audience's gaze) are wholly engaged with their own actions. Hence the viewer becomes voyeur.

1. Wang, Qingsong. , viewed November 2001.

2. Wu Hung. 'The Night Entertainment of Han Xizai', in The Double Screen: Medium and Representation in Chinese Painting. Reaktion Books, London, 1996, pp.29-71.