Hiroshi Sugimoto, who graduated from Saint Paul's University in Tokyo in 1970, moved to Los Angeles and completed a Master of Fine Arts at the Art Centre College of Design in 1972. While studying, Sugimoto began working with photography and developed a minimalist style. His early works concentrated on making images of cinemas, theatres and dioramas from local history museums.

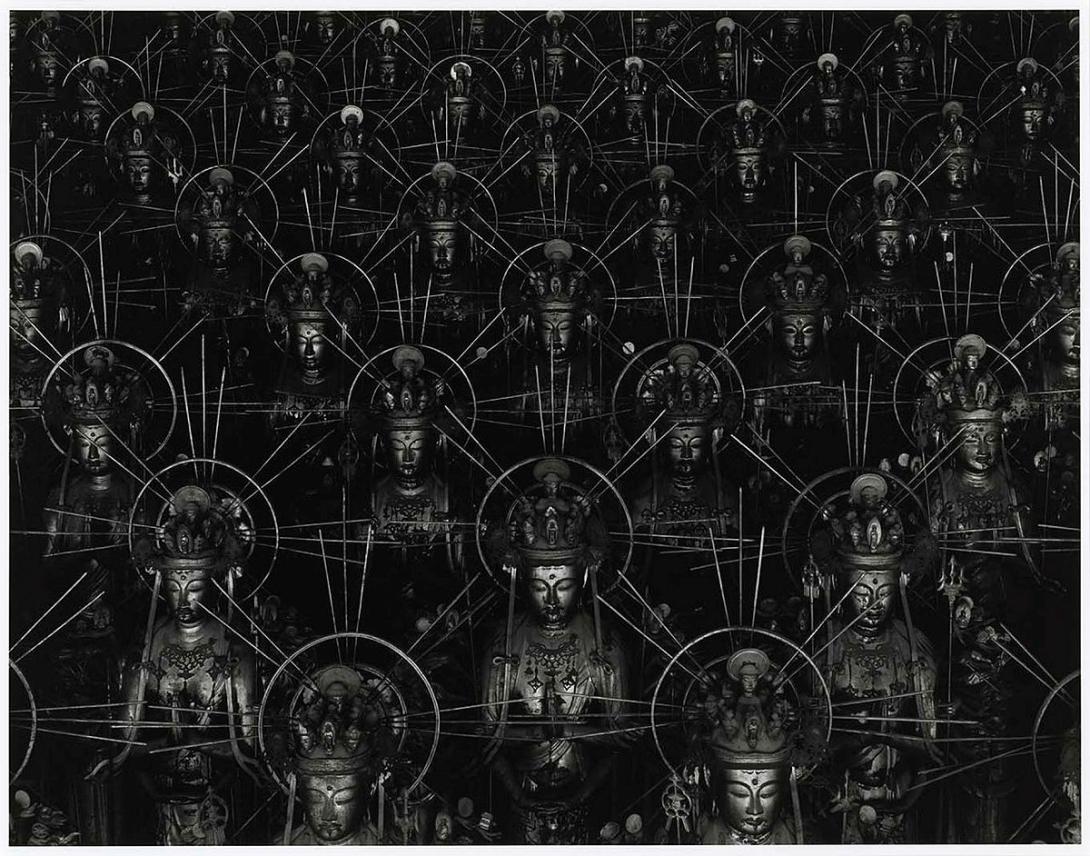

The photographs that make up the series Hall of Thirty-Three Bays were made in 1995 and taken at the twelfth century Sanjusangendo Buddhist temple in Kyoto. The temple is a towering wooden hall (117 metres high) with a long, sloping tiled roof. Placed against one wall, standing ten deep, are 1000 life-size sculptures of the Bodhisattva Kannon. In the centre of these figures is a larger seated Bodhisattva. The Kannon deity is the Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva - the Bodhisattva of compassion. These deities are beings that have chosen to remain in the sentient world to help mortals attain enlightenment. Carved and gilded by more than 70 artists in the twelfth century, this temple was originally built to commemorate the Emperor Go-Shirakawa. It was believed that the world would end 2000 years after the Buddha's time so this temple was also created to either dispel or prepare for the end of time through the offering of the 1000 Kannon. In keeping with traditional aesthetics of the late Heian period (794-1184), these sculptures are meant to inspire a sense of unearthly and detached beauty. The Bodhisattva take on different forms required of them as they embody the idea of unlimited compassion, thus none of the 1000 figures is identical. The original temple construction and sculpting of the Bodhisattva began shortly after 1164 and was completed in 1266.

The photographs that make up the Hall of Thirty-Three Bays were taken at dawn when the first rays of sun strike the entire stretch of the Kannon. Sugimoto's photographs document the incremental variations of these figures. Curator Dana Friis-Hansen describes the impact of this repetition and the effect of 'seeing' these images one after another:

'In the temple series, we first study the multiple statues in any single picture to discern subtle differences in their carved faces, then we move on to look at another picture, and another, and another, and finally pulling back to see and connect the entire set. This repetition is at first hypnotic, even confounding, but it becomes refreshing, revitalizing our vision, forcing us to look closer and harder at the most subtle details not only in these works but in the world around us'.(1)

The mesmeric effect achieved in these photographs mirrors the devotional aspects of the Kannon itself. These sculptures, and the temple, were made as an offering, and to some degree are meant to symbolize the resplendence of a 'heaven on earth' in preparation for an apocalyptic end of time. Thus, a notion of infinity is made physical in the sheer scale of the repetition achieved by the 1000 figures. These photographs by Sugimoto are sombre and sublime responses to the Sanjusangendo Kannon. At the turn of the twentieth century, when reflections on the past resonated in tandem with reflections on what the future may hold, Sugimoto invoked images made during the twelfth century in his response. Writer Alexandra Munro has said:

'Like his seascapes, each identical in composition yet distinctly different in appearance, Sugimoto seeks with "The Hall of Thirty-Three Bays" to invite contemplation on infinity... Dismissing the conventions of modern photography and the politicised antics of much contemporary art, his photographs are not meant as objects to be regarded, but rather as images of ritual reality to be experienced.'(2)

1. Friis-Hansen, Dana. 'One and Another: Hiroshi Sugimoto's Hall of Thirty- Three Bays', in Sugimoto.[exhibition catalogue], Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston and Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 1996, p.19.

2. Munro, Alexandra. 'Hiroshi Sugimoto: Ritual reality', in Beyond the future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, South Brisbane, 1999, p.24.