Aisha Khalid

APT9

Born 1972 Lahore, Pakistan

Lives and works in Lahore, Pakistan

Aisha Khalid is one of a generation of artists from Pakistan who have transformed the tradition of miniature painting into an internationally celebrated form of contemporary art. In recent years, Khalid’s practice has extended to significantly larger paintings, murals and installations. In her textile works, she draws on a form of visual language rooted in Persian culture, with its emphasis on pattern, colour and geometry, as well as incorporating designs from traditional Charbagh gardens. These large-scale hanging tapestries, embedded with thousands of long, gold-plated pins, employ Khalid’s foundational skills and show the confident hand of a miniaturist, together with her sensitive understanding of pattern making and her love of textiles. The sharp pins pierce through several layers of cloth and add a three-dimensional, sculptural element to the works, creating a tension between beauty and danger, pain and fragility.

Aisha Khalid draws on Persian and Islamic art, experimenting with scale, technique and subject matter to translate historic traditions into an art practice that is politically and socially relevant today. In her transformation of elaborate techniques, Khalid subtly comments on our contemporary world, particularly issues relating to gender and violence.

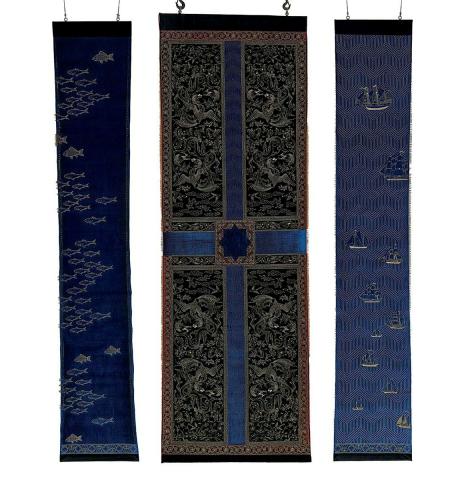

Taking its title from the words of the thirteenth-century Persian poet Rumi, Water has never feared the fire 2018 is a triptych of tapestries created with thousands of pins. The central panel is based on the quadrilateral garden layout of the Charbagh (‘four gardens’ in Urdu). The Charbagh represents the quintessential Islamic garden from the Qur’an, and is a symbol of paradise on earth. The four sections constitute the four gardens of paradise and are delineated by four water channels representing the rivers of paradise. Within the sections are dragons and phoenix — creatures that appear widely in Persian art — while the outer panels’ geometric designs represent water, in which sea creatures and ships symbolise trade and the movement of peoples and cultures. Motifs on one side of her tapestry are barely distinguishable on the reverse, including a central design, which, in Mughal architecture and gardens, would be the space where the heavenly symbols culminate.