Any artist and curator team can apply to curate a show in the Australia Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, thanks to Creative Australia’s open call process. When Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist Archie Moore and curator Ellie Buttrose decided to put themselves forward in 2022, it was the beginning of an arduous 18-month-long labour of love that would result in an historical first for Australia. Here, Ellie invites us behind the scenes of Moore’s kith and kin 2024 at the 60th Venice Biennale.

Archie Moore's Inert State 2022 (Commissioned for ‘Embodied Knowledge: Queensland Contemporary Art’ 2021 by QAGOMA / Courtesy: Archie Moore and The Commercial, Sydney), installed on the QAG Watermall in 2022, with a distant view of Robert MacPherson's Mayfair: (Swamp rats) Ninety-seven signs for C.P., J.P., B.W., G.W. & R.W. 1994–95 (Purchased 1998 with a special allocation from the Queensland Government. Celebrating the Queensland Art Gallery's Centenary 1895-1995) / © The artists / Photograph: N Harth, QAGOMA

The conversation about Archie and I pitching for the 2024 Australia Pavilion evolved from working with the artist on his commission Inert State 2022 (above) for ‘Embodied Knowledge: Queensland Contemporary Art’ (at QAG, 2022–23, co-curated by Katina Davidson, Curator, Indigenous Australian Art). Archie’s practice struck me as timely for the pavilion, at a moment when the necessity of truth-telling as a building block for a shared future is starkly apparent. In late 2022, when the Venice Biennale call for expressions of interest opened, we hashed out a two-page proposal for an exhibition titled kith and kin. The artist described it as a ‘map of relations which connects life and death, people and places, circular and linear time, everywhere and everywhen to a site for quiet reflection and remembrance’.

A month later, good news arrived: we were one of just five teams shortlisted and were invited to prepare a larger, more detailed proposal, based on which the jury of Australian and international arts professionals would choose the successful team. We called Kaurareg and Meriam architect Kevin O’Brien, Principal at BVN Architecture, who previously worked with Archie on projects for the Biennale of Sydney and for Griffith University Art Museum here in Brisbane. While our project was intended to take place in Venice, Kevin would ensure that a First Nations’ recognition of place would underpin the exhibition design. We also asked Euahleyai/Gamillaroi legal scholar, author, broadcaster and filmmaker Larissa Behrendt AO, and Bunjalung curator and writer Djon Mundine OAM, if they would be our ‘correspondents’, acting as sounding boards for the project, writing for the publication, and recording videos for the website www.kithandkin.me. Larissa and Djon have often written on Archie’s practice through his career, so we knew that we could rely on them to deeply understand and champion the project. Unlike the majority of the national pavilions in Venice, we proposed to make kith and kin in situ. Over the following month, we finalised the details of the proposal: 3D digital renders of the artwork, an overview of the ideas, fabrication plans, timelines and budgets; a publication outline; public programming ideas; and, of course, pandemic contingencies. We submitted our proposal in late 2022.

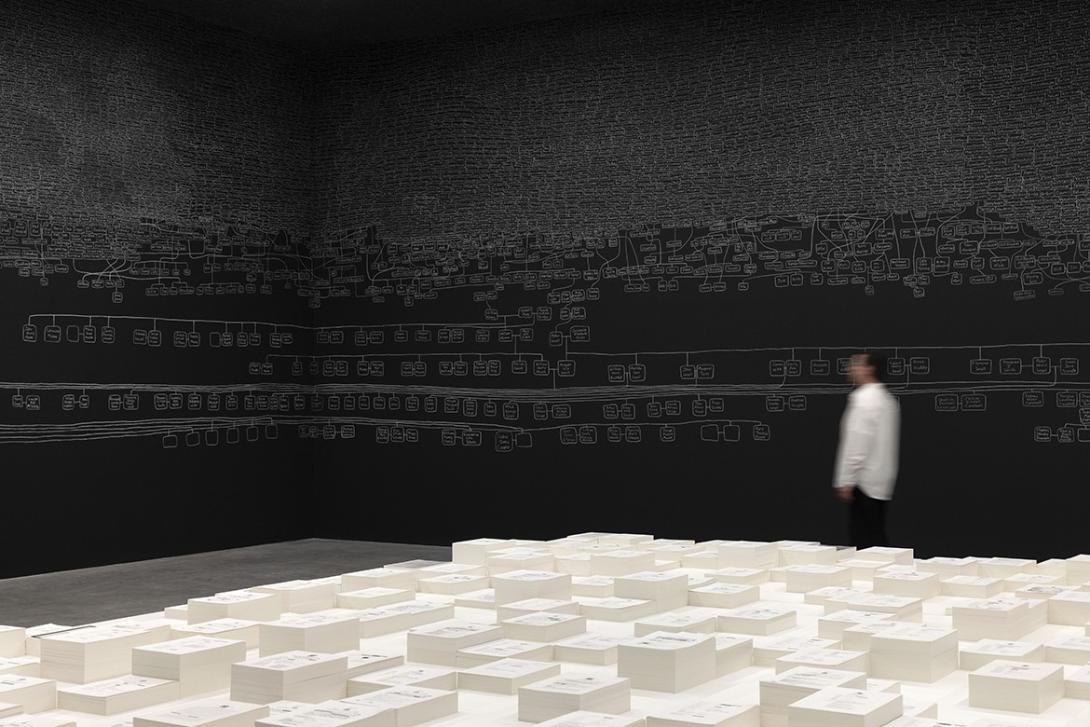

Archie Moore with kith and kin (installation view, Australia Pavilion, Venice Biennale) 2024 / Presented to QAGOMA and Tate by Creative Australia on behalf of the Australian Government 2024 / © Archie Moore / Photograph: Andrea Rossetti / Image courtesy: The artist and The Commercial, Sydney

There was silence over the summer break, and then, in the early days of 2023, we got the call: kith and kin would premier in the Australia Pavilion at Venice. The opening was a little over a year away, so with the team at Creative Australia, we began trialling structural elements and negotiating with fabricators. Landing in March 2022 for our first site visit with Kevin O’Brien and project manager Tahmina Maskinyar, we met with Venetian-based Australia Pavilion Manager Diego Carpentiero, our ‘man on the ground’. We taped out our plans in the space, discussing how to slow audiences down and conferring with builders about how to transform architectural plans into artworks. Diego regaled us with tales of the city en route to the next appointment or meal.

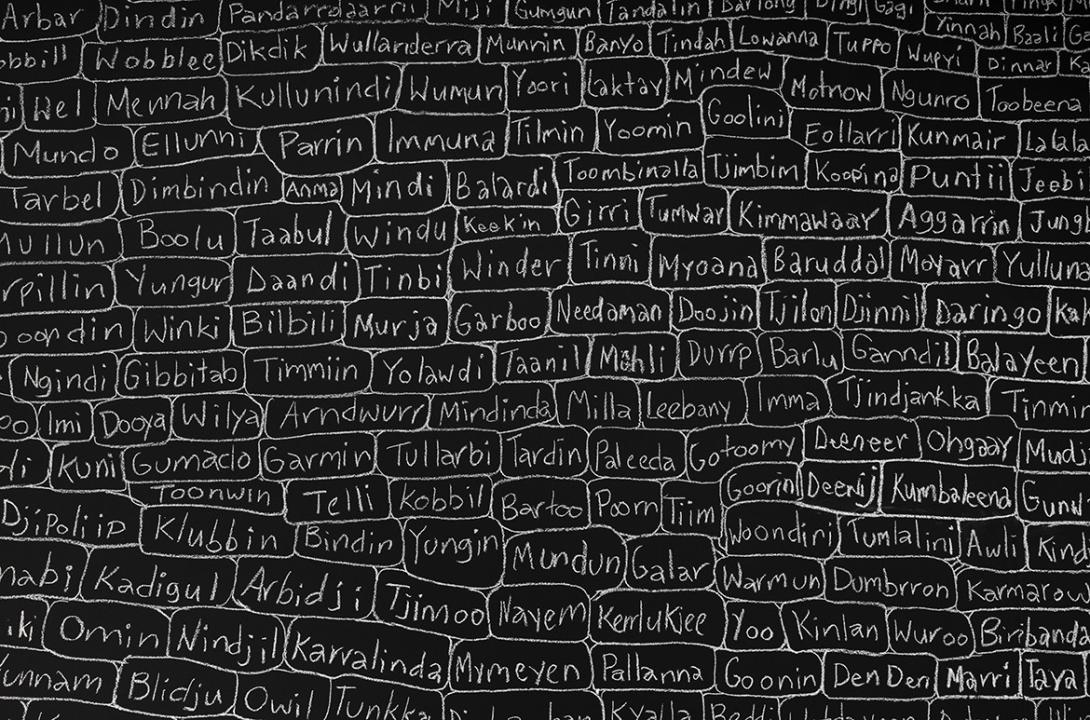

Back in Australia, Archie gathered together research on his family, speaking with relatives on Facebook about new leads, finding connections on the genealogical website Ancestry.com, requesting documents from the state archives, uncovering cadastral maps, searching through historical newspapers on Trove — the National Library of Australia’s search engine — and painstakingly looking through electoral rolls. Back in Australia, Archie gathered together research on his family, speaking with relatives on Facebook about new leads, finding connections on the genealogical website Ancestry.com, requesting documents from the state archives, uncovering cadastral maps, searching through historical newspapers on Trove — the National Library of Australia’s search engine — and painstakingly looking through electoral rolls.

He uncovered new material but was also confronted with missing information, destroyed archives and refusals of access. The personal archive Archie constructed fed the artwork, which traces his family tree across the five-metre-high and 60-metre-long walls of the Australia Pavilion. The artist was aided by designer Sebastian Adams, who digitally stitched together a virtual version of Archie’s drawings so we could zoom in on the finest details and visualise the pavilion from the other side of the world.

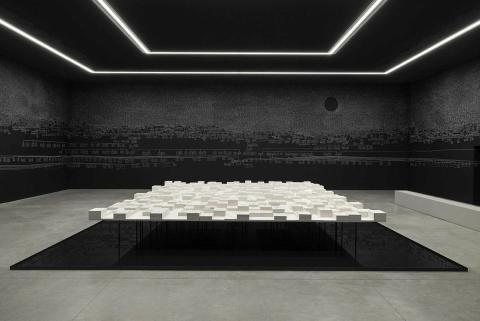

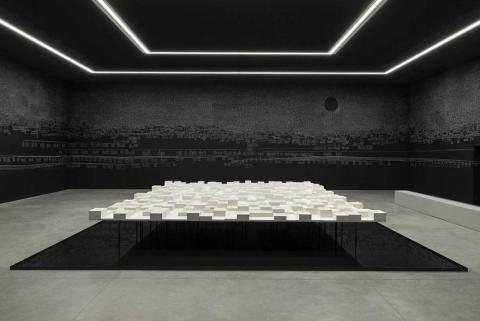

Archie Moore's kith and kin (installation view, Australia Pavilion, Venice Biennale) 2024 / Presented to QAGOMA and Tate by Creative Australia on behalf of the Australian Government 2024 / © Archie Moore / Photograph: Andrea Rossetti / Image courtesy: The artist and The Commercial, Sydney

Archie and I also edited an accompanying publication with Bundjalung editor Grace Lucas-Pennington, which includes essays by Archie, myself, Larissa, Djon, Bundjalung writer Melissa Lukashenko, writer and academic Macarena Gómez-Barris, and a discussion between Dhanggati/Gumbayngirr First Nations language expert Raymond Kelly, linguist Felicity Meakins and anthropologist Diane Bell. These texts draw on art history and literature, social and legal histories, and linguistics and anthropology. Each entry attests to Archie’s impressive ability to summon his personal and familial stories and to visualise more than 65 000 years of First Nations kinship connections to this continent; producing these in visual form, he has provided a timely reminder that everyone in the world shares common ancestors and, therefore, kinship responsibilities to each other.

In late February 2024, we arrived in foggy, cold Venice. We were one of the very few teams working on site, as other pavilions — in their earlytwentieth- century buildings — were being renovated. (The Australia Pavilion is the only one built in the twenty-first century.) It would be another month before most artists, curators and project managers filed into the Giardini to install artworks made in studios and at fabricators closer to the artists’ homes. Across the Australia Pavilion’s ceiling and down walls covered in blackboard paint, Archie — with the assistance of technicians Erika Scott, Luke Sands and Sam Bloor — began tracing his family tree in white chalk. It was physically gruelling work, so there were regimented breaks for tea and stretching. Midway through the drawing process, a pond was welded and waterproofed in the middle of the room. After weeks and weeks of drawing, the mural was finally complete, and the team switched to laying out the 576 stacks of white paper, most of which are coronial inquests into First Nations deaths in police custody since 1991 (this date references the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody 1987–1991). The strict linearity of the installation makes for exacting work. With the last pages in place, the pond was filled with water and, for the very first time, we saw kith and kin. A shared giggle travelled around the room as we realised how eerily the installation resembled the original rendered images in our proposal.

Archie Moore's kith and kin (installation view, Australia Pavilion, Venice Biennale) 2024 / Presented to QAGOMA and Tate by Creative Australia on behalf of the Australian Government 2024 / © Archie Moore / Photograph: Andrea Rossetti / Image courtesy: The artist and The Commercial, Sydney

After living in a bubble comprised of just the agile production team for nearly two months, the clock ticked over to mid-April. Suddenly, hundreds of thousands of people from the art world washed into the Venetian lagoon, and into the Australia Pavilion. Archie and I were on a relentless schedule of tours and media interviews, reaching out to say a quick ‘hello’ to friends between engagements. A day of public programs at Fondazione Querini Stampalia with ArtReview placed the themes that underpin kith and kin — art for incarceration and for the enactment of First Nations language maintenance — within a global context. The talks included contributions from Djon; Gamilaraay and Yawalaraay journalist Lorena Allam; Türkiye Pavilion artist Gülsün Karamustafa; artist and co-founder of For Freedoms (an artist-run platform for civic engagement), Hank Willis Thomas; Director of Curatorial Affairs at First Americans Museum, Dr heather ahtone; Hãhãwpuá (Brazilian) Pavilion curators Arissana Pataxó, Denilson Baniwa and Gustavo Caboco Wapichana and artist Ziel Karapotó; and Bundjalung and Kullilli broadcaster Daniel Browning. At the official opening of kith and kin, Archie reminded the crowd that the water of the canal, beside which we were standing at the time, is connected to lagoon, to the Adriatic Sea, and to all the world’s oceans, including the ones that surround Australia — a simple observation that contained within it the immensity of earthly connection.

On the morning of Saturday 19 April, after talking through some maintenance procedures at the Australia Pavilion (the logistics do not halt at the opening of a show), Archie, Tahmina and I catch the vaporetto to meet Djon, Mikala Tai (Head of Visual Arts, Creative Australia), and Amanda Rowell (Archie’s gallerist and founder of The Commercial) at Ca’ Giustinian, the home of La Biennale di Venezia. Along with hundreds of artists, curators, commissioners, politicians, dignitaries and media, we enter the Sala delle Colonne — drinking in its late-Venetian Gothic style — for the Biennale Arte 2024 awards ceremony. As the proceedings come to a close, there is only one prize left: the Golden Lion for Best National Participation. The president of the jury, Julia Bryan-Wilson, announces ‘Australia’. Archie and I rise to the stage to thank the judges — Julia, Alia Swastika, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Elena Crippa and María Inés Rodríguez. Following a media scrum, and being interviewed for the Biennale’s archive, we are finally off to meet our family and friends, and to celebrate with all the people whose dedicated efforts and support ensured the project came to fruition.

Ellie Buttrose is Curator, Contemporary Australian Art.

kith and kin 2024

- MOORE, Archie - Creator

Digital story context and navigation

KITH AND KIN | INSCRIBING A LIFEExplore the story

'Archie Moore: kith and kin'

Sep 2025 - Oct 2026

Digital Story Introduction

KITH AND KIN | INSCRIBING A LIFEIntroducing 'kith and kin'

Read digital storyRelated resources