Lindy Lee | Artist

An infinite unfolding

By Ellie Buttrose, Peter McKay

Artlines | 2-2021 | June 2021

| Editor: Stephanie Kennard

When COVID-19 deferred last year’s Foundation Appeal, the generosity of Foundation members, local art lovers and particularly Cathryn Mittelheuser AM, secured its intended focus — a group of works by contemporary Australian artist Lindy Lee — for the Collection. Peter McKay and Ellie Buttrose visited Lee in her studio to learn first-hand about the personal experiences and global histories that have informed this evocative and deeply reflective practice.

Zen Buddhism is very important to you and your practice. Could you explain where that came from?

Zen Buddhism was an influence before I even knew what it was. I remember as an 8-year-old, there was a boy really misbehaving in class. The teacher exclaimed, ‘Johnny, its 12 o’clock! Don’t you know this moment will never happen again! Wake up to yourself. This is your life’. I don’t think Johnny cared, but it made a big impression on me. I looked at the clock and watched the second hand sweep around and realised, That’s true! That was my first conscious recognition of time and a huge epiphany.

How do you engage with Buddhism and the concept of time in your work?

Time is the most basic component of our humanity, but it takes a long time to realise that. My work is all about time. In Zen Buddhism, the essence of being — or the fabric of being — is time. The primary truth is that everything changes from moment to moment: nothing is permanent. That means us, too. For me, this is a very beautiful and poetic way of describing and embracing existence.

It also suggests that we need to embrace diversity because change generates diversity. If everything changes then there are so many manifestations of existence, and these people and their experiences are all equally valid. Change just keeps going on through time creating new things. I try to find different ways to capture this. My work is also informed by meditation. In Buddhism, eternity is not another place; it’s the absolute, infinite unfolding of this continuous now — meaning we are living in eternity right now. We can’t help but do that, except we lose sight of that. Meditation is a method to bring your head, heart and body together in the same place within this eternity — your thoughts, your feelings or spirit and your physical form. Everything of what you are can be tethered together.

Artist Lindy Lee, during 'Moon in a Dew Drop', 2020-21, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney / Image courtesy: Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney and Singapore / Photograph: Anna Kucera

A lot of my work incorporates rain and fire and paper. Inherent in those materials are aspects of time and fragility. I also use light and shadow in my imagery and ink, as well as positive and negative forms in the paper and the cut-out burnt sections. When used together, I think audiences are required to slow down and be present in front of the work, so it’s like a meditation on time. You can’t just look at it and go ‘ok I’ve got that’ and move on like a clear image. That activity of engaging is done in time and becomes a meditation. The repetitious aspect of making the work is also a kind of meditation. You encounter yourself in the process of making.

Zen, and particularly the thirteenth-century Zen philosopher Dōgen, has also helped shape my thinking about identity. My whole life has been consumed by questions of identity: a lack of, or a sense of split. In Genjōkōan, Dōgen says something like, ‘to study the Buddha is to study the self, to study the self is to let go of the self and embrace the 10 000 things’ — meaning, if you want to know who you are, forget your constructions because you already know them. They will confine you. That is not who you are. You are fluid and you are changing. For someone like me, for whom identity has been a big issue, this has been very liberating because damn it we are not just one thing. With that, the whole world becomes something you can play with and really engage in. Some moments might be tragic and sad, but these are still things that confirm your existence. Buddhism is very inclusive in that regard.

While the 2020 Foundation Appeal couldn’t officially proceed, the generosity of our supporters meant that we were able to secure its works for the Collection. These were a major bronze sculpture and 12 works on paper — six abstracts and six using photographs from your family album. Tell us, about the family photographs and working through your sense of identity.

I think I was quite unhappy as a child. Working through the family photographs is a way of working through that. As a child, trying to belong to the dominant culture but being Chinese, I had to deny what I was. An example might be that my friends would always say, ‘Oh Lindy, we don’t even think of you as Chinese’, but really they are saying ‘You can be one of us, but only because we are going to overlook that you are not one of us’. It isn’t meant to be, but it’s a very insidious and subtle thing. The pain it creates in that person who is tactfully othered is extraordinary. Looking back through the photographs I realised that my parents also denied their Chinese-ness, too. In the 1950s and 60s, they felt it would be better for their children not to speak Cantonese. I also began to see again the extraordinary family trauma experienced in the transition from China to Australia, with the background of the Japanese invasion of China, then the Chinese Revolution. China was decimated after those events and I believe very strongly that trauma is transgenerational.

Elliptical rain 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Transformation by fire 2017

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Earth and fire 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

How did your parents cope?

My parents went through a lot and they buried it. They pushed it away to end it. Fair enough. But it has to come out somehow. Following the Long Path, for instance, captures the last time my mother saw my father for ten years as he travelled to Australia and forged a life there. My mother was six months pregnant with my older brother, and that’s my oldest brother standing on the left. I was born much later in Australia. I can’t help but feel my mother’s anguish here. Her husband is about to go. She doesn’t know what’s going to happen and the country is in revolution. For me this photograph is the summation of decades of trauma through war, invasion, separation, social tumult and discrimination. The more I look into the family photographs, the more I realised how much had been… not forgotten, but pushed away. How much certain family dynamics that played out are a result of all this.

What about the other moments captured in the photographs?

Leaving Birth and Death shows when my mum and two elder brothers finally came out to Australia, almost ten years later. My father and my second oldest brother never got on particularly well, and I think only meeting at the age of eight, it was too late to forge much of a bond. My father was quite patriarchal and demanded love and respect, but of course you can’t demand those things. Once you do, you aren’t going to get it.

Following the Long Path 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Leaving Birth and Death 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Write, erase, re-write 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Write, Erase, Re-write pictures me, my sister and my mum at a Chinese community event in Brisbane. My parents were very involved in the Chinese community in Brisbane. It was an important part of their social network, but I just didn’t feel a part of it. If anything, it made me feel more alone. It was the combination of being forced into the situation, to spend time with your own people, but at the same time being told you mustn’t be like these people. It increased the sense of polarisation, and the sense that I could never belong to either. As a child, you can’t make sense of it, it just exists as discomfort.

This is an image of me and my sister at the only Chinese restaurant at the Gold Coast in the ’50s. There’s a really strong sense of broken threads in my family because of everything we went through, but it’s important for me to show us together here in this moment. My mum had a really tough time coming to Australia with no language, but I think having two daughters helped her.

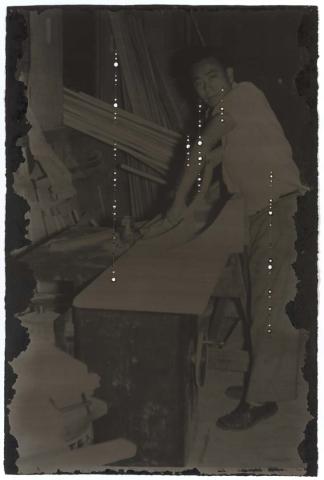

The last photograph is my dad. I need to start this one, too. Dad had a backyard factory in Kangaroo Point making furniture. He made dining tables, coffee tables, buffets. I didn’t really like them, but he was proud. Funnily, all my life I heard him complaining about his competitor CRO, he even sued them at one stage. My partner, Rob, who’s a photographer and prints all my photographs, well it turns out his grandfather owned CRO. We didn’t meet until we were 40, and it’s lucky because if we met before that it would have been too soon.

Rob’s a great technician and always after the perfect print, but he also knows how to play with registration and overprinting a negative image onto a positive to get a raised effect. So there’s experimentation. Sometimes I’ll want to run it through the printer multiple times and he says we’re printing it too dark, but really I’m the queen of black! Between the two of us, though, we get it right — we balance out the image and the experimentation.

Whispering Truth 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Joy, joy, Joyce 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Tell us about the patterns you burn into these abstract and photographic works. The ink stains, the burn patterns, the absence of some sections: with these actions, you’re putting them in the past, and you’re placing them within the cosmos.

Exactly, but the ink stains and the burning of these works is also about adorning the story to enhance the moment that the photograph conveys. I’m not really adding anything new to it, just placing some emphasis. The ink stains focus the attention and can strengthen an emotion. Sometimes it feels quite transgressive burning these family images, but that’s useful in that it keeps me from going too far.

The purely abstract works on paper can be quite hard. I feel like I am only just beginning to understand the possibilities there. When I put them outside, I tend to leave them for a couple of weeks. Sometimes the ink might start to look a bit faded and then next time it rains, I’ll put more ink on and leave it to pool and dry again. It’s a flexible process.

What about Unnameable?

The flung ink is a Chinese calligraphic tradition in which you meditate, then take up a flask of ink and splash it on paper and everything in the universe has conspired until that moment to deliver that action. That’s where my two-dimensional flung bronze works came from.

I wanted these to be more three-dimensional, so I asked UAP can I fling bronze into a bucket of water and they said no very firmly because it would explode. Fair enough.

Bronze has a very high melting point, so I bought a carton of Pauls custard and started to drip molten lead into it and it did the perfect thing. It created all sorts of little intriguing shapes. Then we scanned the ones that could rest as a stable form safely on the ground and had them scaled up.

The splash is really the emblem of everything. It’s unique. It’s historical and unhistorical. We are all the accumulation of all history and, getting back to the classroom awakening, this moment that produced the splash will never come again: and that is unhistorical. Everything is a moment, but the bronze splash embodies this sense of moment very clearly. The family moments are exactly equivalent to those splashes; paired with the works on paper, the demonstration of this sense of cosmos is much stronger. Everything is embedded in cosmos.

Peter McKay is Curatorial Manager, Australian Art, and Ellie Buttrose is Curator, Contemporary Australian Art. They spoke with Lindy Lee in February 2020.

Unnameable 2017

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

No up, no down, just is 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator

Resting in a cloud of stars 2018

- LEE, Lindy - Creator