Margaret Olley’s generous life in art

By Michael Hawker

June 2019

The enduring appeal of Margaret Olley AC lies not only in her long career as a prolific and talented artist, but also in her charismatic, matter-of-fact character. As a mentor and friend she exerted a lasting influence on many artists over several decades, and was a muse for others, from William Dobell in the late 1940s through to Ben Quilty in 2010. The way Olley conducted her extraordinary life — of great highs and lows but on her own modest and honest terms — resonated with the Australian public, and for this and her luminous still lifes and interiors she became one of the country’s most cherished artists. Art was her passion; however, she was also a dedicated and generous philanthropist to national, state and regional art institutions, and her creativity combined with her legacy is deserving of celebration. She was her own person and not one to follow fashions, saw no reason to be tied in marriage with children and gave herself fully to art. Painting was at the very core of Olley’s purpose and existence: her life’s direction was guided by this lodestone, and it was her early years in Brisbane that set the course of this generous life.

Margaret Olley was born in Lismore, New South Wales, in 1925, the eldest of three children. Her parents moved to Tully, north Queensland, and then Tygalgah, near Murwillumbah, north-east New South Wales, while she was a child, before moving to Brisbane at the age of 10, where her journey to becoming an artist began. She attended Somerville House for girls as a boarder from 1937 to 1940, where the school’s progressive art teacher Caroline Barker was quick to recognise Olley’s talent. Barker was the first of many artists and teachers who would have a profound influence on Olley, and in time Olley herself would assume the role of mentor, encouraging younger artists in her midst.

In Barker’s classes the young Olley forged the first of her many great artistic friendships. This was with Margaret Cilento, who described Olley in her school days as: ‘Always rushing around, quite rebellious, doing her own thing. She wasn’t particularly academic, so she wasn’t interested in any of that’.1 Olley left school in 1940 before sitting her final exams. Nevertheless, Barker recommended to Olley’s mother Grace, who was steering her daughter into a nursing career, that Margaret attend art school, and she was enrolled at Brisbane Central Technical College in 1941.

Olley was unhappy with the creative restrictions imposed on her at the college. For one exam, Olley recalled, she and a number of students were given such low marks that they marched indignantly to the education department offices in Brisbane’s old Treasury building and demanded a review. Their protests were given short shrift: ‘This is wartime’, an education department employee said to them. ‘If I hear another word out of you, I’ll close the art school’.2 Thankfully, Olley never lost her defiant nature. In 2006, as an 83-year-old National Art School alumnus, she became a vocal advocate of saving the 75-year-old school from merger plans with the University of New South Wales College of Fine Arts.3

On Barker’s further recommendation, the frustrated Olley moved to Sydney in 1942 and enrolled in a diploma of art at East Sydney Technical College (later the National Art School). Here she studied sculpture with Lyndon Dadswell and painting with Herbert Badham, Douglas Dundas, Frank Medworth and Dorothy Thornhill. Art historian Christine France notes that ‘Medworth’s drawing classes were of particular significance to Olley’ because they underscored that

looking at objects with different intentions changes the viewer’s perception of that object and that it is this training in looking at things differently that Olley has found to be of great value in her work.4

In 1945 Olley also benefited from attending Jean Bellette’s night-time life-drawing classes, where she met artists David Strachan and Anne Wienholt who both became life-long friends.

The postwar period was an exciting time for Olley when she began to connect with many Australian art luminaries, including Russell and Bon Drysdale, Donald Friend, Justin O’Brien and Sidney and Cynthia Nolan. She also co-managed the eighth Contemporary Art Society exhibition in 1946 with Mary Webb and Margo Lewers, one year before graduating from East Sydney Technical College with first-class honours.

Throughout the 1940s, Olley experimented with a wide range of subject matter for her works, including landscapes, figures and still lifes. Frequent trips to Donald Friend’s home in the old gold mining town of Hill End, west of Bathurst, New South Wales, was an inspiration, as were the buildings of Brisbane. Paintings Olley made of Brisbane at this time — including Queensland Club 1946; St Paul’s Terrace (Spring Hill) 1946; St Pauls Terrace shops (John’s place?) 1947; Evening, Stanley House, South Brisbane 1947; The Treasury Building (Brisbane) 1947; Breakfast Creek Hotel (Brisbane) 1947; and Upper Edward Street, Spring Hill c.1948 — all have an almost ghost-town feel, enhanced by a subdued colour palette. Postwar austerity was suffocating this sprawling country town, and Olley yearned to escape and explore a larger world. Her paintings reflect this frame of mind.

Olley’s well-received first solo exhibition was opened on 30 June 1948 by Russell Drysdale at the Macquarie Galleries, Sydney. Four months later, she held another successful exhibition at Moreton Galleries, Brisbane, and both cities would remain the focus of her exhibiting career. Despite this early recognition, Olley’s sales were not enough to allow her to travel, and missing out on the coveted New South Wales Travelling Art Scholarship in 1948 was a source of frustration. Happily, however, fellow Queensland artist Anne Wienholt, whose family was privately wealthy, generously gave Olley the funds she needed to travel abroad in 1949. (This act of support generosity left a lasting legacy.) Olley studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris and travelled further to Italy, Spain and Portugal. It was productive time during which she sent back 30 drawings to the newly established Marodian Gallery, later renamed Johnstone Gallery, run by owner Brian Johnstone, and 17 drawings to Macquarie Galleries in Sydney to be sold. The Johnstone Gallery would be Olley’s principal exhibition venue in Brisbane, where she held many well publicised, sold-out exhibitions, from 1950 until its closure in 1972, after which she was represented by Philip Bacon Galleries.

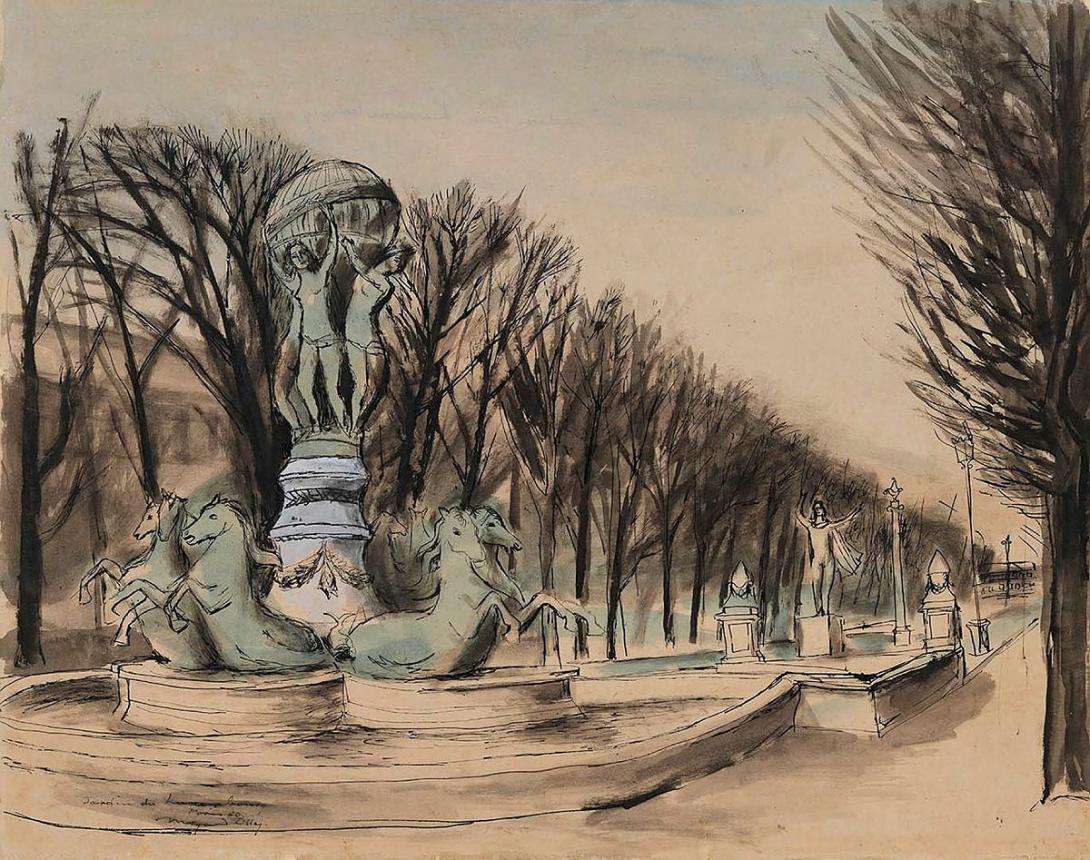

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris 1950 / Watercolour, gouache, pen and ink on paperboard / Purchased 1950 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMA

In 1953, following the sudden death of her father Joseph, Olley returned to Brisbane and lived at the family home, Farndon, at 15 Morry Street, Hill End (now West End).5 After time spent abroad engaging with a wider art world, Brisbane no longer seemed quite as stifling. In the first few years after her return, Olley travelled to Sydney from time to time to meet new artists and renew friendships with Donald Friend, David Strachan and Sidney, Cynthia and Jinx Nolan, and these friends visited her in Brisbane too. Closer to hand, a lively art circle surrounded Brian and Marjorie Johnstone’s Brisbane gallery, where Olley met artists Ray Crooke, Jon Molvig and Charles and Barbara Blackman. The art scene in Brisbane at that time was also invigorated by the appointment of Robert Haines as director of the Queensland National Art Gallery, and by Viennese-born art historian Dr Gertrude Langer’s writing as art critic for the city’s Courier-Mail newspaper.

Olley involved herself in the Brisbane arts scene, painting sets for the Twelfth Night Theatre’s production of Christopher Fry’s Firstborn, and in 1953 Haines commissioned her to paint a mural of the Place de la Concorde for the foyer of the Queensland National Art Gallery for the travelling exhibition ‘French Painting Today’, which brought works by Georges Braque, André Derain, Hans Hartung, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Pierre Soulages to Australia for the first time.6 Olley completed another mural, this time of Brisbane, in the saloon bar of the city’s Grosvenor Hotel, and in July 1954 she worked with Donald Friend on a mural of north Queensland scenes for Brisbane’s Lennons Hotel. Sadly, both murals were later lost to redevelopment.7

To undertake the Lennons mural, Olley and Friend returned to Brisbane from a painting trip by jeep further north to Magnetic Island, and after completing the work resumed their travels to Cairns. Paintings made at this time, such as Cane farmer’s house (North Queensland) 1955 and Childers garden 1956, completed on a sketching trip to Childers with artist Moya Dyring), demonstrate Olley’s strong use of line and blossoming use of colour. Art critic Dr Gertrude Langer commented favourably on Olley’s drawing style on display in an exhibition at Johnstone Gallery in June 1956: ‘Everything is expressed with pure line and no upholstery, Miss Olley’s line is open, firm, seemingly effortless and full of vitality and strength’.8 Olley had honed her drawing skills while travelling in Europe, but her return to the tropical light and vegetation of Brisbane rekindled her love of colour, with which she was enthralled as a child living in Tully and Murwillumbah.

Towards end of the 1950s, however, Olley’s alcohol consumption began to affect her artistic output. Concerned artist friends Elaine Haxton and Fred Jessup encouraged Olley to seek help, while her family encouraged her to open an antique shop at Stones Corner, Brisbane. Olley recalled a moment of realisation on the way home from the shop in 1959:

I had to change trams at South Brisbane, which was very run-down in those days, full of depressed-looking hotels, real bloodhouses. I leant against a pole at the tram stop and thought, How can I go on living until I am old enough to die? How will I ever live to be old enough to die? Wasn’t that a terrible thought? Pathetic. Some moments in your life you never forget. I can still conjure up the feeling as I stood there thinking, How will I ever live to be old enough to die? If that is not a death wish …9

As a result of diligently attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings over a number of years, by force of her own will and with the support of her network of friends, Olley managed to turn her life around, becoming sober in 1959.

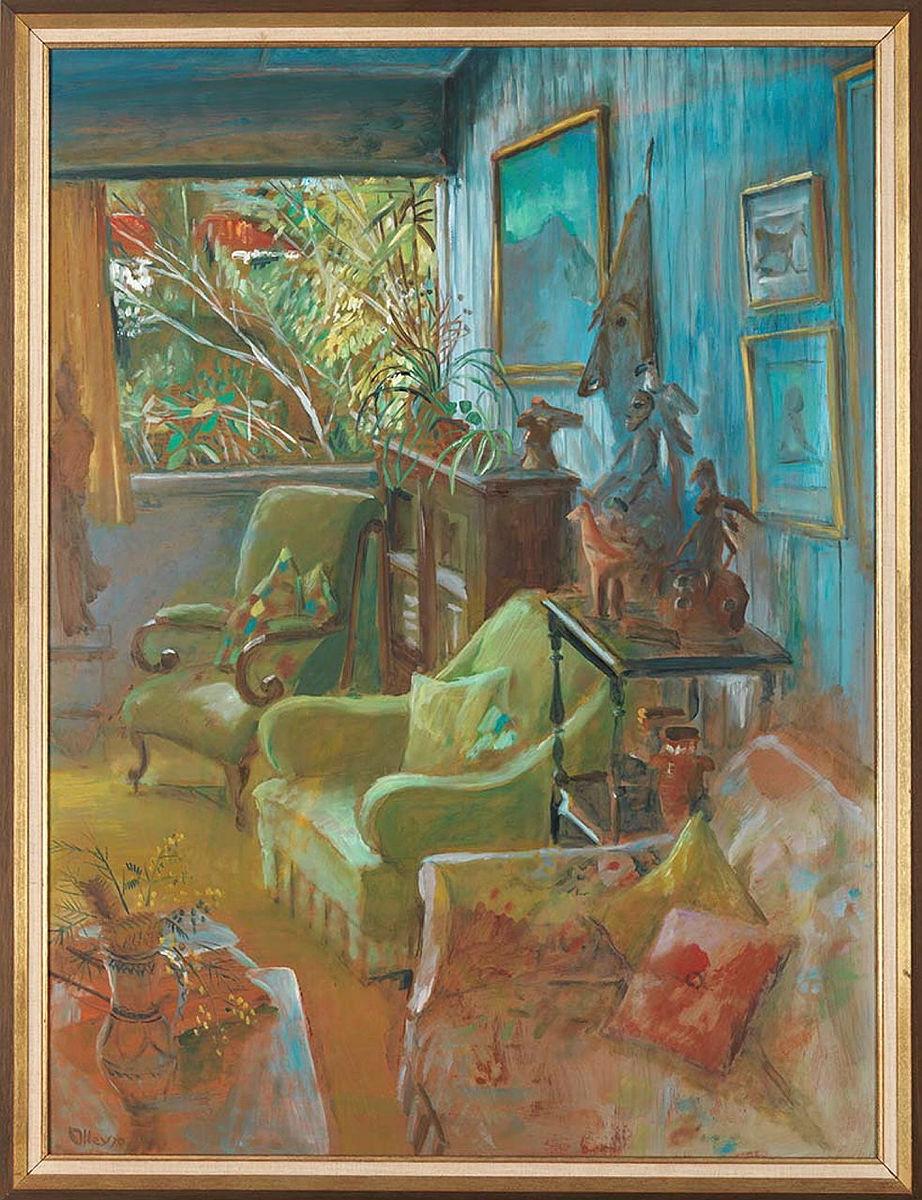

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Interior IV 1970 / Oil on composition board / Gift of the Margaret Olley Art Trust through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2002 / © Margaret Olley Art Trust

The streets and gardens of the Brisbane of Olley’s youth had changed little in her absence — the city was still the same large country town on the banks on the meandering Brisbane River. In Meg Stewart’s biography Far From a Still Life: Margaret Olley (2005), Olley states:

I’d liked Brisbane ever since I was a child, so really I was quite happy to be back there. Farndon was just a street back from the river. From my bedroom I could see little bits of its greeny-coloured water. At night the river cruise would come past. It used to go about as far as Lone Pine and there was dancing on board. You’d hear faint chugging; the music would be slowly swelling as the boat came closer then fade away. Then just as we were about to fall asleep, the faint sound of music would drift off the water again as it came back down.10

The refuge of Farndon would play a pivotal role in Olley’s life, tying her to Brisbane for many years. The property was divided into flats, with Olley and her mother occupying one side, two flats on the other side and another flat downstairs where her brother Ken and his family lived. Her studio was also downstairs, at the front. ‘It had a strong wooden floor, windows at one end and typical Brisbane lattice’.11

The calm presence of Farndon, with its high-ceiling, generous rooms and lush subtropical garden, is captured in a series of Olley’s first interiors created in 1970 that were displayed in the Johnstone Gallery in October that year. Christine France wrote of these works:

As in her still life the formalist values of painting are the prime concern of Margaret Olley’s interiors yet the impossibility of divorcing the narrative overtones of any interior painting gives these works an intimacy not necessarily present in the still life.12

Spare bedroom 1970 explores the cool depths of Farndon’s rooms, a play of diagonal light emanating from the open doors in the foreground and background. In the case of Interior IV 1970, with its collection of family furniture, paintings and sculptures, the work can function as an expanded self-portrait. However, it can also be seen as an exercise in how forms are placed within the pictorial space:

Angular sculpture offsets the rounded forms of the chairs, which in turn sets up a rhythm with the framed paintings on the wall and are compositionally balanced by the cut-off form of the sculpture at the end of the room.13

If we compare this painting with Interior VIII 1970, which depicts the same room but from a different angle, we gain a different interpretation of the interior again. Light streams in from the windows overlooking the verdant garden, overwhelming the contents of the room. ‘By taking the viewer closer to the window and using light as the primary subject matter, Olley changes the reading.’14

There is a wonderful stillness to these nostalgic and timeless works. They show signs of human occupation, but those people are left beyond the frame. Interiors were a creative space for Olley. She explained:

I’ve always been intrigued by interiors, you gain a lot of information from a room. I’ve also always liked artists who painted interiors; Sickert, Bonnard, Vuillard, Matisse. An interior will result in a portrait of the person who lives there, but it’s also to do with approaching the room as if it was a person whose portrait you are painting.15

In the same year as Olley made these works, her close friend David Strachan was killed in tragic motor vehicle accident at Yass, New South Wales. Olley made a series of paintings of Strachan’s house in Sydney and exhibited them at the Johnstone Gallery in 1972 under the title ‘Homage’. In their rendering of possessions and convivial bottles and wine glasses, the paintings capture something of Olley’s devastation and the pair’s close friendship.

In 1980 Olley’s studio and many early paintings were destroyed dramatically in a fire at Farndon. Olley spoke emotionally about the traumatic loss of her home:

Losing things in fires is so final. For years afterwards if I couldn’t find anything I used to say it was in Brisbane. It was almost as if I was denying the fire had happened. I just didn’t want to think about it. It was quite a while before I accepted that Sydney now really was my home.16

For a few years leading up to the fire, Olley had been living between Brisbane, Newcastle and Sydney, working and keeping paintings and art materials in all three locations. Olley’s mother Grace had moved to Sydney earlier so Margaret could better look after her, but she was never told of Farndon’s untimely destruction:

My mother didn’t know about it. I went through all her mail to make sure she never knew — it would have killed her if she’d found out. In her mind the house still existed and she could walk through it as she wished. If that had been taken away she would have been bereft.17

After Farndon was destroyed, Olley continued to use interior spaces as inspiration. Her series of paintings of the Yellow Room — the transitional space between her two-storey house in Paddington, Sydney, and the old hat factory she used as a studio and where she spent most of her time — would evolve into one of her most impressive explorations of interior space. In the Yellow Room, Olley changed the artworks on the walls, introduced a Chinese screen and set up various still-life arrangements.18 The space remained a favourite painting spot, and when Olley’s neighbours living opposite painted their house a darker colour, the change in light in the Yellow Room presented Olley with a whole new dynamic, necessitating a reconfiguration of objects and arrangements.

By using her own home as a subject, Olley was able to mine a rich vein of forms and compositions as subject matter. The most imposing of these later works is Yellow room triptych 2007, where the three panels give a slightly vertiginous perspective. Olley often referenced well-known works by artists she admired in her own paintings by including reproduced works hanging on the walls of the Yellow Room. In Yellow Room triptych, for example, the eye is drawn to Henri Matisse’s Dance 1910 above the fireplace, before moving around the room from object to object. The great success of this painting is Olley’s astute balance of the forms and colours which constitute the space.

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Allamandas I c.1955–58 / Oil on canvas / Purchased 1961 / © QAGOMA

Perhaps of all Olley’s painting styles, still life is what she was best known for. Her lifelong love of nature found expression in her exuberant paintings of flora, which charmed the public and the critics. Reviewing Olley’s exhibition at the Johnstone Gallery in 1960, Dr Gertrude Langer wrote:

Her flower pieces, not by number but by achievement dominate the show. Olley is at her lyrical best when she expands a bouquet of large flowers across a large canvas. These paintings will appeal to lovers of flowers as well as lovers of paintings’.19

Art critic for the Australian newspaper Pamela Bell expanded on their appeal:

There is an earthy quality about her still lifes, which are never idealised or romanticised. She reminds you that the roots of all things are in the earth and her fruits and flowers and the harvests of the sea and land are not simply static [but] suspended by her at one moment in the timeless ritual of bloom and fall, ripening and decay.20

Many of her still life paintings from the 1960s, such as Alamandas I 1960 and Lemons and oranges 1964, consist of the casual assemblages of branches of citrus fruit and flowers that could be gathered from Brisbane’s lush subtropical gardens by Olley on her walks. These works have a lovely informal feel enhanced by the random placement of flowers and fruit and the colourful, broad application of paint across a large canvas. Their dreamy mood of joyous abundance inspired both local appreciation and healthy exhibition sales.

The 1960s was a decade of tremendous success for Olley. In 1962 she became perhaps the country’s best-known woman artist after her sell-out exhibition at the Johnstone Gallery, and by successfully investing her income in property she ensured she did not have to make a living from painting.21 On 22 October 1962 Brisbane’s Courier-Mail newspaper ran an article with the headline, ‘Margaret Olley top woman painter’, which stated ‘she sold 38 paintings for £3000, doubling the record set by Australian women painters’.22 In artist and critic James Gleeson’s introduction to the catalogue for Olley’s solo exhibition at the Johnstone Gallery in 1964, he perhaps managed to give the best synthesis of Olley’s contribution to the annals of Australian art when he wrote:

I can think of no other Australian painters of the present time who orchestrate their themes with such uninhibited richness as Margaret Olley. She is a symphonist among flower painters; a painter who calls upon the full resources of the modern palette to express her joy in the beauty of living things. There is nothing skimped, cramped, lean, under nourished or improvised in her pictures. They inevitably give you an impression of such fullness and abundance that you are reminded of a harvest festival.23

The years 1962 to 1965 are central to understanding the momentum of Olley’s career success. During these two years she was awarded nine prizes for her painting — including the Helena Rubinstein Portrait Prize (1962), Redcliffe Art Prize, Bendigo Art Prize and Finney’s Centenary Art Prize (1963) — which firmly established her national profile.

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Lemons and oranges 1964 / Oil on composition board / Purchased 1964 / © QAGOMA

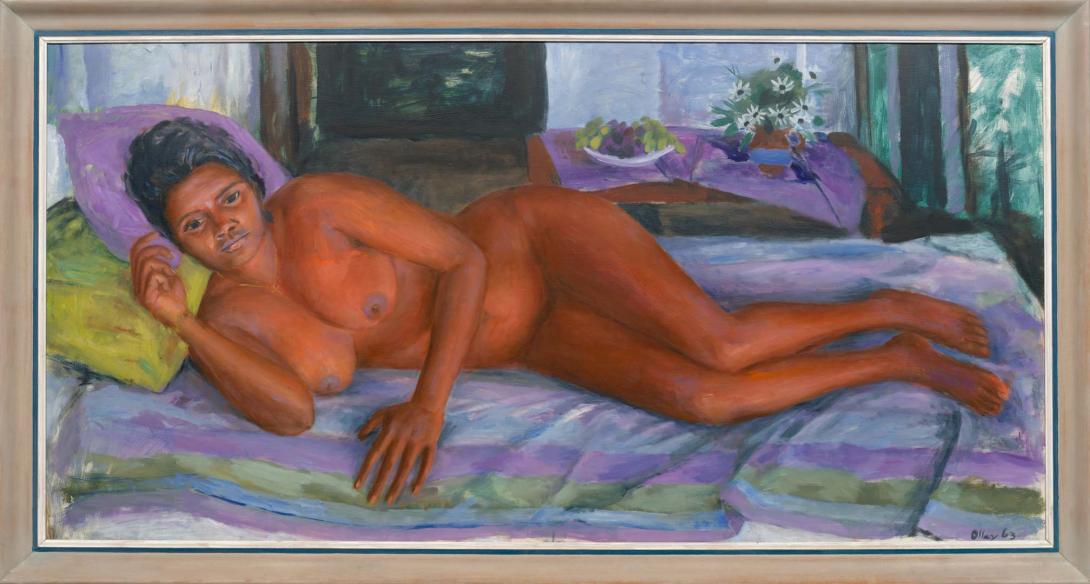

Olley’s exhibition at the Johnstone Gallery in 1962 caused a sensation with its inclusion of eight large-scale reclining nudes of young Aboriginal women. This was the first substantial showing of nudes at the Johnstone Gallery, with the possible exception of drawings by Jon Molvig in the 1950s, and it had a considerable impact on an otherwise conservative Brisbane. Although there were 32 other paintings in the show, due to their large dimensions the nudes were given prominence in the gallery’s spaces. To quote one exhibition visitor, ‘You didn’t know where to look’.24

Dr Gertrude Langer’s review of the exhibition stated that Olley ‘invites us to share her delight in what is obviously beautiful in nature, flowers, fruit and the young female form’. Langer noted that the neutral treatment of the figures made ‘no social comment in contrast to the treatment accorded painting of Aboriginal people by many other artists’.25 While there is a certain truth to Langer’s position, today it is inadequate. Although Olley perhaps intended no social comment, this was a time when government policies sought to assimilate Aboriginal Australians and the historic 1967 referendum — which acknowledged Aboriginal Australians’ growing civil and legal rights to determination and to be included in the national census — was yet to be won. That said, there is a simple sequence of events that led to the series, and Olley’s matter-of-fact approach to the nudes appears to ring true. Moreover, painted at a time when so many images of Aboriginal people were clearly derogatory, these works present positive representations of beauty, Westernised as their ideals might be.

Olley’s models came from a hostel in Russell Street, South Brisbane, established in 1953 by Englishwoman Joyce Wilding. Originally set up to provide boarding for Aboriginal women and to assist them with finding employment, the centre grew to become the One People of Australia League (OPAL) House in 1962.26 Olley travelled daily from Farndon in nearby Hill End to her antique shop in Stones Corner and would have noticed the hostel’s women residents on the tram. Mrs Wilding later organised those interested to pose for Olley.

As with Olley’s interiors, the paintings are essentially about formal arrangements and colour, as well as creating a dialogue with the Western painting tradition of the reclining nude. In Susan 1962 and Dina 1962, Olley plays the skin tones of her reclining models against the warm and cool colour combinations of fabrics and objects that surround them. Susan, with its clear references to Édouard Manet’s famous 1863 painting of Olympia with attendant servant, was a much-loved work of Brian and Marjorie Johnstone’s displayed in their Brisbane home until their estate was sold off. Daphne 1964, with its representation of a seated nude washing her feet, references Edgar Degas’s female figures depicted in similar poses.

In her studio under Farndon, Olley also completed a series of paintings of clothed and seated Indigenous women and men. QAGOMA's Susan with flowers 1962 is a major work from this group, and was awarded the 1963 Finney’s Centenary Art Prize, judged by the Gallery’s then director Laurie Thomas. This is the only work in the series in which the model is depicted standing. In these works, Olley’s subjects are a vehicle for the study of light and the form of the figure, often set against groupings of flowers and fruits. Again, while we might find the limitations of this approach lacking today’s awareness, these contemplative works certainly show a sensitivity and feeling for the individuals depicted. Banana cutters 1963, also from this group, is a more active representation featuring bananas cut from the garden.27 While a different kind of postcolonial controversy, distinct from the prudish embarrassment of their original showing, continues to surround these works, their complex social, historical and aesthetic value also persists — arguably making them some of Olley’s most intriguing works from her Brisbane years.

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Dina 1963 / Oil on canvas / Gift of Miss Pamela Bell 1982 / © Margaret Olley Art Trust

Olley’s self-portraits track her artistic life from beginning to end. In these works, she captures her reflection in mirrors and depicts her personal possessions. Portrait in the mirror 1948 begins the series, and everything portrayed in this painting foretells the trajectory of Olley’s life. The young artist looks outwards, into the future, while the emphasis in the foreground on fruit and flowers references the natural world in which she revelled as a child. Images of postcards and sculptures signify the twin inspirations of art history and travel that fed her creative drive to paint.

As the years progress, Olley’s physical image in her self-portraits seems to recede into interior spaces, with the room surpassing her reflected image in importance. In Afternoon reflections 1972, Olley’s figure is only one more form within the room, surrounded by paintings on the wall, a paper lantern hanging from the ceiling, a mantle clock and objets d’art — all facets of the room’s personality. Similarly, the self-portraits Olley produced in the 1980s and 1990s show her image reflected in the mirror of her dressing table. In Self portrait 1982, for example, the vibrant Chinese floral-patterned backdrop, shells, books, pens, scissors, cotton reel and toiletries give a feeling of life’s daily rituals.

A passion for travel was central to Olley’s life and art. Time spent in Europe (1949–53) taught her to use travel as a stimulus for creative output. After spending time in London, Olley and fellow Australian artists Mitty Lee-Brown and Fred Jessup travelled to Paris in 1949. Soon Olley took over the lease of a farmhouse in Cassis, near Marseilles in the south of France, from Lee-Brown, but frequently returned to the capital. Later, she met up with artist friends Moya Dyring, David Strachan and Wolfgang Cardamatis, and they established a routine of working or visiting galleries in the morning and attending classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in the afternoon. There are many examples of Olley’s bold drawing style from this time, including Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris 1950, in which a wash of watercolour and gouache heightens and fleshes out the scene.

Between 1967 and 1968 Olley travelled three times from Brisbane to Papua New Guinea (then still a territory under Australian Government control), producing works on all three visits. When in PNG, Olley stayed with art collector and plantation owner Geoff Elworthy, and during her second trip she travelled with artist and designer Douglas Annand up the Sepik River by canoe. On her third trip, Olley visited Goroka, capital of the Eastern Highlands Province, and attended a sing-sing festival of song and dance. Simple, quickly worked watercolours such as Kuku kukus, Goroka, New Guinea 1968 capture the energy of the places and the people Olley visited. Later, Papua New Guinean art Olley collected on her travels would make an appearance in her interior paintings, such as Interior IV 1970.

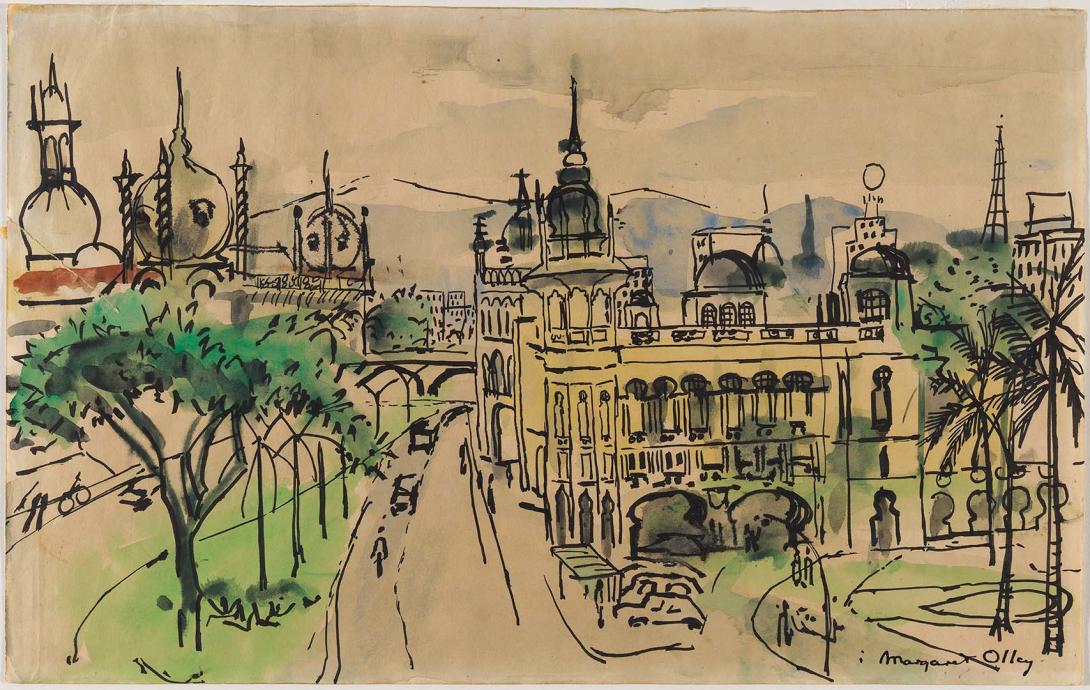

In 1969 Olley travelled extensively in Malaysia, Cambodia and Indonesia, and in Bali she stayed with Australian expatriate artist Donald Friend.28 Her feeling for these locations is captured in Kuala Lumpur 1969 and Jalan Tokong, Malacca 1969 through a confident use of line and broad colour washes. In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s Olley continued to travel overseas, often inspired by the prospect of seeing an exhibition by an artist she admired. In 1975, for instance, she visited Paris for a Paul Cézanne retrospective. When abroad, Olley always purchased items that she took back to Farndon, and later to her home in Paddington, Sydney. New Guinean artefacts, Asian sculptures, woven kilims and objets d’art that caught her eye for their form and colour were taken home to be repurposed in new works of art.

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Kuala Lumpur 1969 / Watercolour and ink on paper / Gift of the Margaret Olley Art Trust through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2012 / © Margaret Olley Art Trust

Olley had a great capacity for friendship, not only with other artists — with whom she made many convivial sketching and painting excursions — but also with supporters and dealers, such as Brian and Marjorie Johnstone and Philip Bacon AM. These lifelong friendships were strengthened by a process of exchange and mutual recognition.29 Early friendships with artists in Sydney found expression in William Dobell’s 1948 Archibald Prize–winning portrait Margaret Olley, which made Olley an unwilling art-world celebrity, as well as in Russell Drysdale’s portrait of the same year, while much later Jeffrey Smart would paint Second Study for Margaret Olley in the Louvre Museum 1994–95. Her friendships extended to a later generation, too, as she acquired the works of younger artists, including Cressida Campbell, Nicholas Harding and Ben Quilty. These artists, in turn, also created portraits of Olley, including Quilty’s 2011 depiction of her which, like Dobell’s before it, won the Archibald Prize. While Dobell’s portrait presents Olley in an almost full-length fancy dress and an elaborate hat, Quilty’s is an unflinching close-up of a sun-damaged and truthfully aged face. In both, Olley’s bright eyes command the viewer. Olley is the only subject to win the prestigious Archibald twice (not counting self-portraits).

Olley stayed on her friend the poet and critic Pamela Bell’s property Aroo at Boonah, and while there she indulged her love of landscape, painting works such as Boonah landscape Mt Alford c.1960 and Boonah landscape 1962. Olley’s portrait of Bell won the 1962 Helena Rubinstein Portrait Prize, but was later destroyed in the Farndon fire. Olley also knew the reclusive Scottish-born artist Ian Fairweather, and would visit him at his makeshift hut on Bridie Island off Brisbane. Olley respected Fairweather’s privacy, and only ever visited him with a few other people she felt would be of interest to the artist.30 Unusually, Fairweather painted the ‘portrait’ work MO, PB and the ti-tree 1965 to record a visit by Olley (MO) and Bell (PB) to Bribie for a picnic under the ti-trees, and Fairweather and Olley corresponded regularly.

Throughout her life, Olley’s friends helped her through her darkest times. They assisted her not only with dealing with her alcoholism in the late 1950s, but also when her dear friend David Strachan died in 1970, Farndon was destroyed in 1980, her mother’s death in 1982 and when Olley suffered severe depression in the early 2000s which, as she explained in 2008, ‘plunged her into a temporary abyss where painting became impossible’.31 A friend suggested Olley consult a psychiatrist and, after changes to her medication, ‘gradually the smoke lifted and within months Ms Olley was painting again’. Afterwards she stated, ‘If you’re feeling depressed, for heaven’s sake, go and seek help!’32

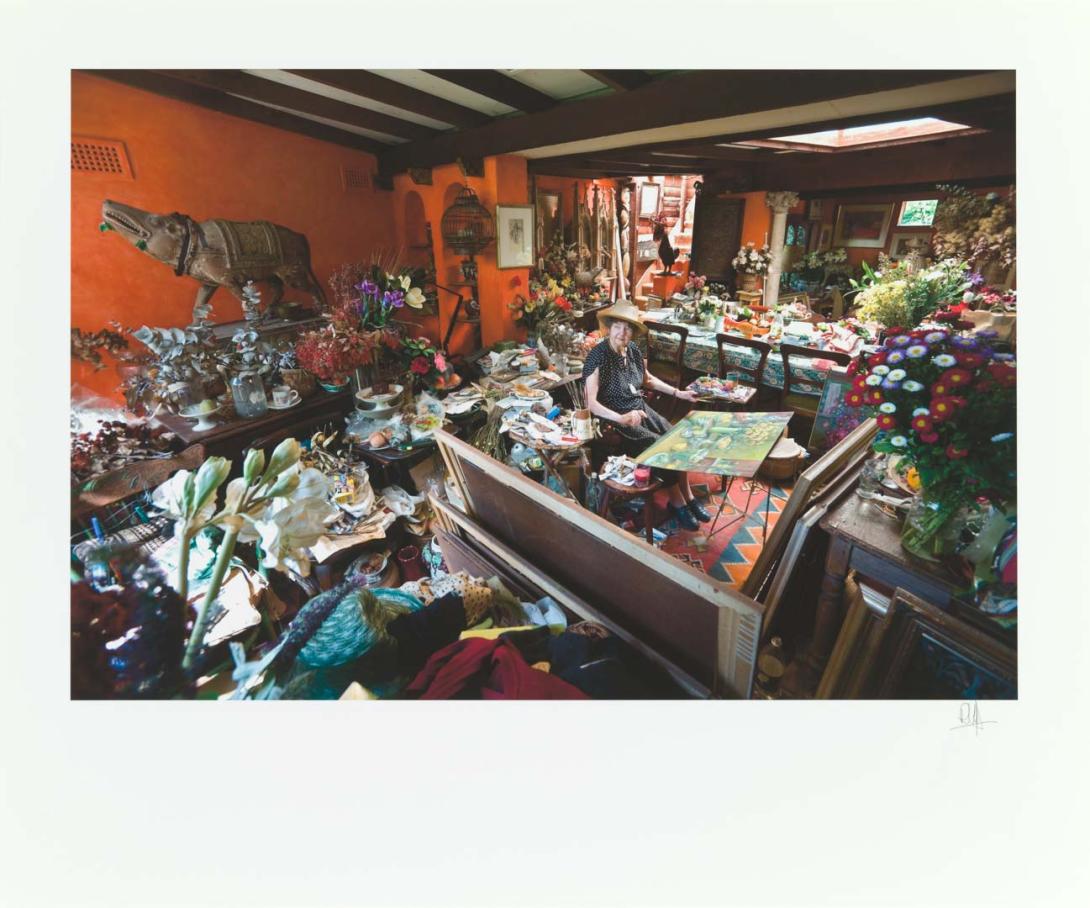

R Ian Lloyd / Canada/Australia NSW b.1953 / Margaret Olley in her studio in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia at 9:22am on December 13th, 2005 2005, printed 2009 / Giclée print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Ultra Smooth archival paper / Gift of the artist through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2010. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program / © R Ian Lloyd

In 1990 Olley established the Margaret Olley Art Trust to donate works of art to public collections throughout Australia. The 1990s were also a time when her achievements became more widely acknowledged. In 1991 Olley was appointed Officer of the Order of Australia (AO), and in 1997 she was declared an Australian National Living Treasure. By June 2001 Olley had given more than 93 artworks to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, personally or through the Margaret Olley Art Trust, and in 2006 she was awarded the Companion of the Order (AC), ‘for service as one of Australia's most distinguished artists, for support and philanthropy to the visual and performing arts, and for encouragement of young and emerging artists’. Other galleries to significantly benefit from her benefaction include the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; New England Regional Art Museum, Armidale; Newcastle Regional Art Gallery; and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane.

Olley’s inspiration for this generosity can be traced back to 1944 when she moved to a rooftop flat at 20 East Crescent Street, McMahons Point, Sydney, with Margaret Cilento, whose mother, Lady Cilento, visited regularly, often accompanied by art collector and Cilento’s godfather Howard Hinton. Hinton would have a lasting influence on Olley. She stated:

[H]e was the very first person I knew who bought art and then gave it away. He lived very simply in a room in a boarding house at Cremorne and used to donate paintings to the Armidale Teacher’s College. You could link my own donating back to his example.33

Curator and friend of the artist Barry Pearce distils our understanding of Margaret Olley:

With her marvellous network of friendships, her house which hosts a dazzling alchemy of things which turn into paintings, her countless adventures across the world to look at art which impresses her, her refreshing frankness concerning any issues of the day, and in general her overwhelming zest for life, it is too easy to summarise her identity in an anecdotal sense, and regard her paintings as a part rather than the essence of it.34

Painting was indeed at the core of Olley’s being. Through art she avoided direct messages or causes, preferring to lovingly express nature’s beauty and bounty and the love for her friends and her surroundings, and it was the act of painting that helped her overcome the negative effects of alcoholism, loss, loneliness and depression throughout her long, productive, celebrated and extraordinarily generous life.

Margaret Olley / Australia QLD/NSW 1923–2011 / Spanish bottles 1985 / Oil on board / Gift of Ann Gruen in memory of her mother, Margaret Darvall (by exchange) 1987 / © QAGOMA

This essay by Michael Hawker (curator, Australian Art) was first published in Margaret Olley: A Generous Life [exhibition catalogue], 2019, QAGOMA, Brisbane.

- Meg Stewart, Margaret Olley: Far from a Still Life, Vintage, Sydney, 2012, p.57.

- Stewart, p.73.

- Art school merger plan draws out critics’, Australian, 11 October 2006, p.4.

- Christine France, Margaret Olley, Craftsman House, St Leonards, NSW, 2002, p.14.

- Margaret Olley’s mother, Grace Olley, purchased Farndon as a real estate investment in c.1940. Located on a large block bounded by three streets, it was originally built as a private schoolhouse but had been turned into flats.

- France, p.34. The exhibition ‘French Painting Today: A Loan Exhibition Arranged between the French and Australian Governments for Showing in Hobart, Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, January—September 1953’ showed at the Queensland National Art Gallery from 11 April to 8 May 1953.

- Terry Shanahan, ‘Time’s called on pub mural’, Sunday Sun, 9 February 1986.

- Art Review by Gertrude Langer, ‘Olley drawing full of vitality’, Courier-Mail, June 1956.

- Stewart, p.325.

- Stewart, p.273–4.

- Stewart, p.273

- France, p.53.

- France, p.53.

- France, p.54.

- Meg Stewart, Margaret Olley: Interiors and Still Lifes, Lismore Regional Gallery, 2006, p.24.

- Stewart, Margaret Olley: Far from a Still Life, p.450.

- Stewart, Margaret Olley: Far from a Still Life, p.450.

- France, p.109.

- Art Review by Dr Gertrude Langer, ‘Show by M. Olley’, Courier-Mail, 9 October 1960.

- Pamela Bell, ‘Cornucopia of colour’, Australian, 30 September 1977.

- Barry Pearce, Margaret Olley, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1996, p.17.

- ‘Margaret Olley top woman painter’, Courier-Mail, 22 October 1962.

- James Gleeson, Introduction to Margaret Olley catalogue, Johnstone Gallery, Brisbane, 1964, unpaginated.

- Glenn Cooke, interview with John Cuffe, Brisbane, 3 March 1997.

- Art Review by Dr Gertrude Langer, Courier-Mail, 22 October 1962. In comparison, the celebrated allegorical series ‘Love, marriage and death of a half-caste’, known as the ‘Brides’ series, is one of Arthur Boyd’s defining contributions to Australian art. In 1953 Boyd made a trip to Central Australia, where he was shocked and depressed to see the plight of Aboriginal Australians, who were living in shantytowns along dry riverbeds and isolated from the nearby white population.

- The One People of Australia League (OPAL) was formed in 1961 in Queensland, and was comprised predominantly of members from the mainstream Christian churches and service organisations.

- Stewart, Margaret Olley: Far from a Still Life, p.368.

- It is not known whether Olley knew of Friend’s sexual activity with underage boys in Indonesia. While Friend was never charged with any such offence, this information was self-acknowledged in Friend’s diaries that were published after his death. The subsequent revelations on Friend’s conduct in Indonesia warrants declaration in contemporary accounts of history. At an earlier time in their careers, Olley and Friend were very close and it is reported that she had once considered marriage to him.

- Pearce, pp.13, 17.

- France, p.50.

- Stewart, Margaret Olley: Interiors and Still lifes, p.21.

- ‘Depression takes the colour out of life and painting: Olley’, Australian Associated Press Newswire, 5 June 2006.

- Stewart, Margaret Olley: Far from a Still Life, p.109.

- Pearce, pp.17, 20.

Digital story context and navigation

Explore the story

‘Margaret Olley: A Generous Life’

Jun 2019 - Oct 2019