Yuki Kihara in ‘Sis’

By Ruth McDougall

‘sis’ February 2024

On a balmy September evening in Brisbane, the spacious, grassy courtyard of the Queensland Art Gallery echoes with the chatter of an opening night crowd. It is the launch of ‘The Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT2002) and the guests comprise a ‘who’s who’ of the art world, together with members of the general public. As the evening progresses, Polynesian grandmothers brush up against government bureaucrats, everyone jostling for a good view of the catwalk, which is decorated in tropical flowers and bathed in bands of brightly coloured light.

A petite, dark-haired ‘Diva’, one of the Pasifika Divas, takes the stage, her hands moving in graceful arcs of the taualuga, a dance performed by chiefly daughters to welcome foreign dignitaries visiting Samoan villages. Dressed in sombre Victorian mourning attire, Samoan-born fa‘afafine Yuki Kihara dances the taualuga gracefully against a projected backdrop of historical images of Samoan women in colonial dress. In English interpretations of the Samoan language, fa‘afafine translates as ‘to conduct oneself like a woman’, but as Samoan artist and academic Dan Taulapapa McMullin observes,‘it is a word:

Encompassing all queer LGBT Samoan people, including gay men, lesbians and female to male transgenders, as well as male to female transgenders . . . Like much Samoan thinking it is not binary and oppositional, but bilateral and reciprocal.1

One of five performances presented at APT2002 by the dynamic Pasifika Divas collective from Aotearoa New Zealand, Kihara’s taualuga announced the birth of her alter ego Salome, a late nineteenth-century Samoan woman who moves fluidly across genders, and through time and space, engaging with the history of colonisation in the Pacific. Inspired by the image Samoan half caste (from the album ‘Views in the Pacific Islands’) 1886 by New Zealand photographer Thomas Andrew (Collection: Te Papa Tongarewa [Museum of New Zealand], Wellington), Kihara’s Salome asserts the historical existence of fa‘afafine in Samoan society, while challenging the influence of colonisation and Christianity on contemporary understandings of gender and sexuality. As Kihara describes:

Today the social equilibrium that has long existed across the gender spectrum prior to missionisation has been greatly disturbed by religious conservatism, which operates an inflammatory televangelism channel in Samoa. Fa‘afafine are used as scapegoats by religious leaders, who increasingly blame homosexuality, HIV/AIDS and even climate change on fa‘afafine.2

Thomas Andrew / New Zealand/Sāmoa 1855–1939 / Samoan half caste from 'Views in the Pacific Islands' (album) 1886 / Albumen silver print / Collection and courtesy: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

In her video performance Siva in Motion 2012, Kihara reprised her alter ego to respond to the devastating Galu Afi tsunami that engulfed Samoa on 29 September 2009. Moving her hands eloquently in the traditional patterns of the chiefly taualuga, Kihara’s Salome hauntingly evokes this traumatic consequence of climate change, prompting audiences to acknowledge the cyclone’s devastation in the same way the taualuga honours important events and individuals.

Siva in Motion builds on the artist’s APT2002 work, and the 2003 performance Lalava Siva, in which Tongan lalava artist Filipe Tohi slowly wrapped Kihara in shiny videotape unfurled from X-rated films on Karangahape Road, one of Auckland’s main streets. In Lalava Siva, a fully dressed Kihara stands still, embodying a Samoan fale (house) that connects family and aitu (spirit), while she is patterned with lalava that renders her sacred. Through the final act of unwrapping and kicking away the dehumanising tape that binds her, Kihara asserts her right to determine her own representation.3

In contrast to this act of agency, the digital rendering of Kihara’s Siva in Motion performance references the practice of chronophotography, which was developed in the nineteenth century to scientifically record and ‘prove’ phenomenological understandings of racial difference, amongst other things. Profoundly alert to the dehumanising historical consequences of European scientific classification of peoples according to ‘type’, Kihara physically addresses the requirement to alter her body to fit new norms by dressing in Salome’s restrictive mourning costume. Her hands, however, remain unadorned and with them, Salome recalls not only the momentous seas that lashed Samoan beaches in 2009’s tsunami, but the waves of change that hit the Samoan islands over a century earlier, in the form of European ships and Christianity. An eerily beautiful and contemporary interpretation of siva (Samoan dance), Kihara’s work draws the past into the present, establishing continuity between the living and the dead.4

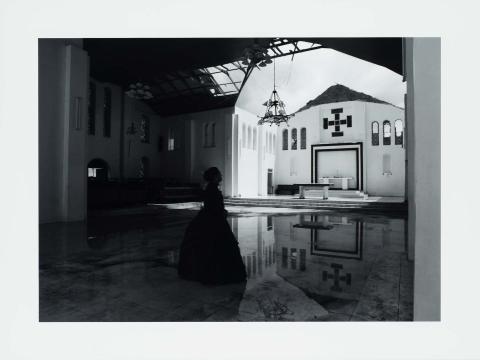

Kihara further explores the complex, interwoven histories of Samoa in the photographic series ‘Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’ 2013. In each of the 20 black-and-white photographs in this narrative tableau, the artist, who is dressed once again as Salome, views historically altered landscapes of her homeland.

The title of the series refers to the late-nineteenth-century French impressionist Paul Gauguin and his ambitious painting Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? 1897–98 (Collection: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Borrowing stylistic traits from Italian Renaissance fresco painting, Gauguin’s work brings together human, animal and symbolic figures in an idyllic Tahitian landscape to explore the nature of life, death, poetry and symbolic meaning. Documenting his own romantic fascination with the South Seas, the depiction of naked and partially clad figures in a tropical landscape mirrors ideas of Tahiti as an Arcadian, exotic paradise that were popular at the time.

Kihara’s works are audacious re-enactments that unravel colonial histories and speak to contemporary climate catastrophe and gender politics. Revealing its narrative almost cinematically across time and space, the photographic tableau documents Salome at iconic sites in the Samoan landscape, in the wake of Cyclone Evan (December 2012) and with the after-effects of 2009’s Galu Afi tsunami still evident. The huge impact of these natural disasters on well-preserved colonial architecture and landmarks, as well as contemporary structures such as the international airport, highlights not only the historical and cultural occupation of the landscape, but the challenges faced by this isolated island nation as it struggles to assert its position on the world stage.5

Yuki Kihara’s tightly corseted Salome faces away from the camera, negating viewers’ access to her thoughts and asserting her gaze over the landscape in front of her. Importantly, Kihara provides Salome with a degree of agency not afforded to the subjects of Gauguin’s paintings, and her photographs provide a postscript to exoticised representations by modern ‘masters’ by questioning stereotypes and asking us to partake in a richer and more equitable exchange.

- Dan Taulapapa McMullin, ‘Introduction: Fa‘afafine studies’, in Dan Taulapapa McMullin and Yuki Kihara (eds), Samoan Queer Lives, Little Island Press, Auckland, 2018, pp.7–8.

- Yuki Kihara, ‘Foreword’, in McMullin and Kihara, p.1.

- Ane Tonga, ‘Declaration: A Pacific feminist agenda’, in Ane Tonga (ed.), Declaration: A Pacific Feminist Agenda [exhibition catalogue], Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland, 2022, p.21.

- Ruth McDougall, ‘Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’, in The 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2015, pp.91–2.

- Ruth McDougall, ‘APT8 highlight: Shigeyuki Kihara’, QAGOMA Blog, 14 October 2015, viewed February 2023.