Khadim ALI: 'Jushn-e-gulle surkh' (Celebration of red tulips) series

By Zoe Butt

April 2005

Khadim Ali was born in 1978 in Quetta, Pakistan, where he currently lives and works. Ali and his family are members of the exiled Hazara community from Mazar-e-Sharif in Afghanistan. His artistic practice is grounded in the discipline and framework of the Mughal miniature. His complex and culturally layered subject matter is directly informed and influenced by his family's plight in exile and their experience of persecution and ensuing violence in Northern Pakistan.

Ali completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Miniature Painting) at the National School of Art, Lahore, Pakistan, in 2003 and has participated in several exhibitions in Iran and Pakistan. His work is held in the private collections of Salima Hashmi and Virginia Whiles (prominent international writers and curators of the contemporary miniature arts of India and Pakistan).

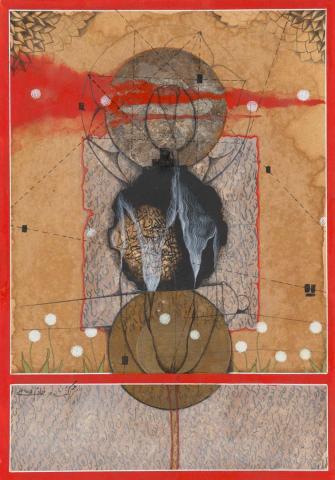

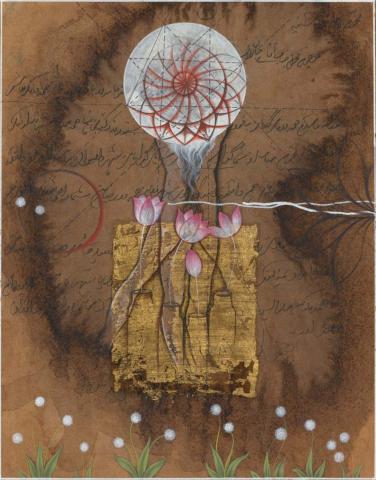

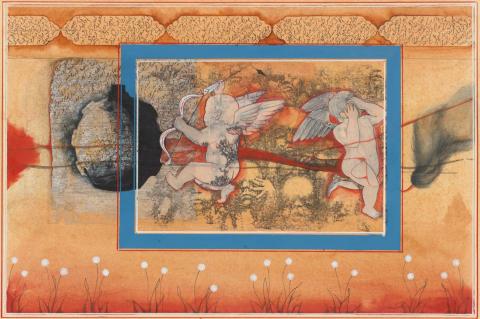

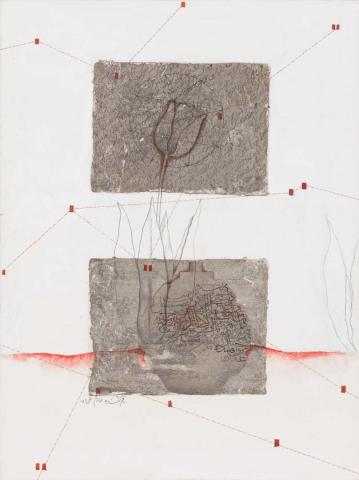

The six works from the series 'Jushn-e-gulle surkh (Celebration of red tulips)' 2004–05 deliver a delicate, yet powerful statement on the Taliban insurrections in Afghanistan and the subsequent genocide of the Hazara people. The Hazara people come from the mountainous central areas of Afghanistan called Hazarajat, and for centuries have endured social persecution resulting from religious affiliations with particular Islamic sects, such as Imami Shi'ism. The 'Celebration of red tulips' is an annual event held in Mazar-e-Sharif, in Hazarajat, timed to coincide with a cherished site of flowers that bloom each spring. Tragically, this site is now a mass grave after the Taliban massacred thousands of ethnic Hazara civilians who were subsequently buried in this sacred place.

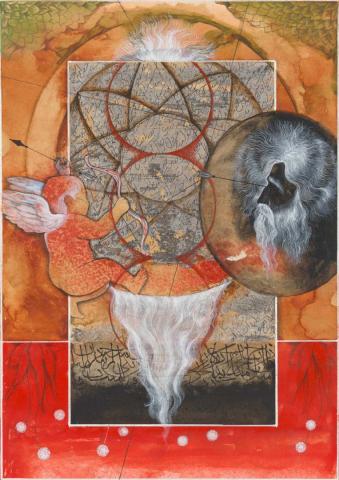

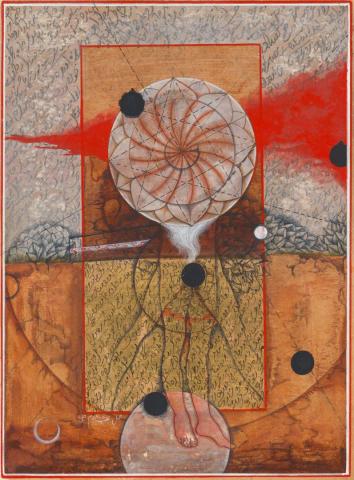

Ali's introspective miniature paintings are eclectically rich in iconography. Through the repetitive use of particular motifs Ali has constructed a compelling visual narrative that uniquely conveys the complex history of this region. In these works Arabic script is inverted and inscribed on images of grenades and tulips that appear to float in the foreground of an abstract landscape. The inverted text refers to the official language of the Taliban whose slogans were triumphantly expressed during the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001, also a sacred site to the Hazara people. Grenades are also the Taliban weapon of choice in civilian warfare. Cupids fly with bow and arrow, their weapons of love aimed at three concentric circles representing the chakras of Buddhist thought. In another image two cupids flee with terror from an approaching grenade, these babies representing the many children who have been killed in Taliban warfare.Vitruvian man, as famously depicted by Leonardo da Vinci, is overlaid in another image with a Buddhist mandala while black grenades are hurled at the centre of the frame. By contrasting this Western symbol of human perfection with that of Buddhist enlightenment, both under threat of destruction, Ali powerfully enquires on the meaning of human life.

These six miniatures vigorously mine references of Eastern and Western philosophy through the frame of the traditional miniature. The overlay of complex cultural symbols deliberately disrupts a single reading of these codes which is a conscious ploy by the artist to demonstrate that the determination of meaning should never be considered a linear process.