HAVINI, Taloi; Russel and the Panguna Mine...

The photographic series ‘Blood Generation’ is born out of the people of Bougainville’s ongoing grief over the loss of their land as the result of mining interests. When Bougainville artist Taloi Havini talks about this history, she speaks passionately of the violent turning of earth to which they belonged, the earth that sustained her people for generations, and of the loss of soil containing graves - not only old graves, but the places where future generations were to be laid to rest. The large-scale photographs comprising the series appear as a landscape with all the sublimity of an expanded vista. They also contain incredible detail that pulls you into intimate textures: earth, skin, pores. The work is all about these two views, and crucially, what happens when they collide.

Beginning with a group of portraits set in the devastated landscape of the contested Panguna mine in Bougainville, the series asks what happens to the surface of the earth and to the skin and pores of the bodies that inhabit it, when you step back and view it as a picture - are these merely things to be consumed? The term ‘Blood Generation’ is the name used in Bougainville to describe children born into the conflict that began in 1988 and raged for a decade between local landowners and the Papua New Guinean government, its business arm Bougainville Copper Limited (BCL) and the Australian owned mining company, Conzinc Rio-Tinto of Australia Limited (CRA), over the land of Panguna. Selecting this generation as the primary subject of their photographic series, artist Havini and photographer Stuart Miller seek to ‘flesh out’ the human cost, engaging with the impact on these young people of the destructive mining and loss of traditional lands.

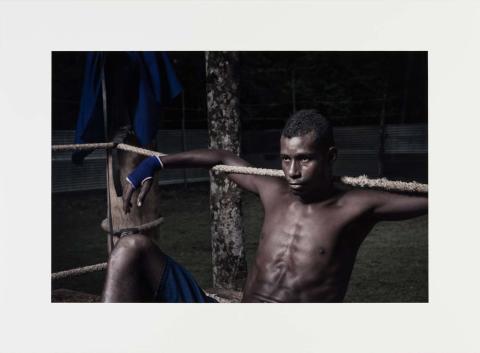

The images are portraits and are deliberately titled with the given names of their subjects: Russel, Mathew, Veronica, Sami, Issac, Mark, Gori. The works are intimate, not only in the close-up, detailed views that they provide but also in the ways that they articulate these individuals’ relationship to where they are. The Gallery recently acquired three of these portraits. In one, Russel is perched at the top edge of the Panguna landscape once occupied by six different indigenous groups, looking reflectively across its now empty, terraced expanse. In another, jean-clad Veronica pauses in the hoeing of the family garden, cultivated on customary land to provide their subsistence, while Mathew sits in the corner of an open-air boxing enclosure, empty and fenced with barbed wire, silently preparing for the next round.

Created as talks resumed around reopening the open-cut Panguna Mine, the series is as much a political statement as it is an aesthetic one. The subjects of the photographs are all a stark reminder that the site of the mine was and continues to be an inhabited landscape. They also assert a fiercely held sense of resistance and cultural autonomy. The people of Bougainville fought for a decade, with flesh and blood because the land isn’t a vista or a commodity but the place of their past and their future. In the words of Bougainville leader Raphael Bele:

To Bougainvilleans, land is like the skin on the back of your hand. You inherit it, and it is your duty to pass it on to your children in as good condition as, or better than, that in which you received it. You would not expect us to sell our skin, would you?(1)

1. Raphael Bele, ‘The Bougainville land crisis’, 1969, p.29, in Moses and Rikha Havini, Bougainville: The Long Struggle for Freedom, New Age Publishers, Surry Hills, NSW, 1999, p.12.

Ruth McDougall, Artlines no.1, 2015, p.38

Text © Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2015