Lure of the Sun: Charles Blackman in Queensland

By Michael Hawker

Artlines | 3-2015 | September 2015

Publisher: QAGOMA | Editor: Stephanie Kennard

The time Charles Blackman spent in Queensland in the late 1950s, late 1960s and the 1980s — and the friendships he made there — were central to his development as one of the most important Australian artists of his generation, writes Michael Hawker.

‘Brisbane beckoned us . . . painter mates in the city . . . and poet friends on their mountain.’1

During his time in Queensland, Charles Blackman was inspired and nurtured by several notable friendships with creative locals, who encouraged him to do some of his most innovative work. This diverse group of talented people included poet Judith Wright and her philosopher husband Jack McKinney; fellow artist Jon Molvig; gallery owners Margorie and Brian Johnstone; modernist architect James Birrell; and the University of Queensland Press’s Frank Thompson.

Wright and McKinney had a considerable effect on the self-taught Blackman, coming to know him through Blackman’s wife, Barbara, who had developed a connection with Judith. Barbara recalls their first meeting, at which she and Blackman were the guests of a group of young Brisbane writers who produced the literary magazine Barjai:

'. . . of all the Barjai guests, two magnetised me. Judith Wright, almost twice my young age, deaf with her awkward off-range voice . . . read her first book of unpublished poems, and JP McKinney, non-academic philosopher, gave a paper on ‘emotional honesty’. Both lifted me sky high and thereafter Jack-n-Judith became lifetime friends.'2

Much later, Blackman also noted:

'The influence of talking to Jack and Judith was a very strong one. Probably I spent as much time listening to them talking about poetry as in doing anything else . . . Jack was at his peak then, a great talker — and he helped me a great deal; he informed a lot of my interests in writing.'3

The work that most honours the friendship they shared is Blackman’s painting The family 1955 (of Judith Wright, Jack McKinney and their daughter, Meredith McKinney), held in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. The painting recalls a winter’s day picnic at Cedar Creek near Mount Tamborine. Meredith McKinney commented that:

'. . . for Charles, my father was probably . . . well to say ‘father figure’ is a very simplistic thing, but the talks that he and my father had were things that sort of drew Charles into new and exciting directions.'4

Blackman appears to acknowledge this link in his Portrait of Jack McKinney 1955 (private collection), painted after spending the winter looking after their house at Mount Tamborine.

Regarded as one of Australia’s finest expressionist artists, Jon Molvig came to Brisbane in 1953–54 to stay with his former East Sydney Technical College classmate, John Rigby. He returned the following year and made the city his permanent home until his death in 1970. As fellow painters, it seems inevitable now that Blackman and Molvig would meet and develop a mutual respect and friendship. In the last months of 1959, Molvig persuaded Blackman to establish an art school some kilometres from Burleigh Heads. Blackman agreed to spend the weekends at the school while spending the week days at his studio in Brisbane. He recalled being driven at a furious pace to and from the Gold Coast, perched precariously beside Molvig in a diminutive Goggomobil.5 Sadly, the art school project was doomed to fail, as Betty Churcher relates in her book Molvig: The Lost Antipodean (1984): ‘The venture ended dramatically after a grass fire (started accidently during an outdoor painting class) had threatened to destroy the house and the surrounding cane farms’.6 Acknowledging Molvig’s influence, Blackman said:

'I got a lot from him although he and I are just about dead opposites. I was concerned with understanding and sympathy with human beings, whereas Molvig was more concerned with the human conflict.'7

Molvig’s 1957 portrait of Blackman alludes to this friendship, but also significantly to some of Blackman’s paintings created in the same year. Surrounded by flowers and accompanied by a white rabbit, the portrait of Blackman is ‘a parody of the imagery in some of the Alice paintings’.8

In The Third Metropolis: Imagining Brisbane through Art and Literature 1940–1970, published in 2007, William Hatherell notes that:

'. . . perhaps the most important cultural institutions to develop in Brisbane during the postwar period were concerned with cultural distribution rather than production, and were located (at least partly) in the commercial sphere rather than either the governmental or the volunteer cultural spheres. These were the publishing houses Jacaranda Press and the University of Queensland Press (UQP), and the commercial art galleries, particularly the Johnstone Gallery. These institutions were particularly important for progressive individual artists in the context of a Brisbane cultural life that was predominately conservative in governmental cultural institutions such as the Queensland Art Gallery and in its volunteer "cultural civil society".'9

The Johnstone Gallery had a national reputation and was also a significant force in promoting Blackman’s work. This shared support and appreciation is most clearly expressed in 1986 by poet Pamela Bell,10 who gifted to the Queensland Art Gallery Molvig’s portrait of 1957 and, the following year, Blackman’s charcoal drawing of Australian writer George Johnston (c.1964).11 She made these gifts in honour of Marjorie and Brian Johnstone in recognition of the huge contribution they made to the knowledge and awareness of contemporary Australian art in Brisbane in the 1950s and 60s and to Blackman’s career. Bell wrote of Blackman’s work:

'I consider it to be a drawing of Charles at his best . . . It represents for me a time of mutual friendship between us all . . . and commemorates a memorable lunch, the Blackmans, Judith Wright, George and I, so again it is in the tradition of the works I am in the process of gifting to the Gallery, which in differing ways are about friendships and eras in the cultural life of Queensland.'12

Blackman was also involved in a number of UQP collaborations, which sprang from his friendship with Frank Thompson, the energetic manager of the press. UQP produced a number of significant books in the 1960s, including Ian Fairweather’s translation and illustration of The Drunken Buddha in 1965 and the artists in the ‘Queensland’ series (interview-based monographs on Blackman, Judith Wright, Milton Moon and Andrew Sibley) in 1967. Thompson first met Blackman after returning from his Helena Rubinstein Travelling Art Scholarship in 1966, and they would often meet at the Royal Exchange Hotel in Toowong. They became close friends, and when Blackman moved to Sydney, Thompson’s interstate travel for work meant that they frequently caught up. This enabled a number of book collaborations, which included the publication of Barbara Blackman’s Certain Chairs in 1968, to which Blackman contributed drawings, illustrating Barbara’s account of their lives in various homes, in which familiar pieces of furniture gave continuity. In 1971, UQP also published Apparition: Poems by A. Alvarez, Paintings by Charles Blackman. The English poet and critic Alvarez originally met Blackman in London ten years earlier, and the publication was the outcome of their close friendship. The seven vivid gouaches, which are reproduced at their original size in the publication, were painted in response to Alvarez’s poems.

Queensland modernist architect James Birrell first met Blackman in Melbourne in the early 1950s through the Contemporary Arts Society. He tells stories of sketching classes and Sunday lunches at Blackman’s home in Chrystobel Cresent, Hawthorn. In Life in Architecture: Beyond the Ugliness (2013), Birrell recalls walks with Blackman to designer and sculptor Clem Meadmore’s place for a ‘drink and conversation’. Meadmore lived upstairs in a Victorian terrace house that overlooked industrial buildings and railway yards, where ‘schoolgirls walked past, sometimes skipped, in their hats and uniforms’, and ‘we studied art books with de Chirico prints in them’.13 (It was Birrell who introduced Blackman to Frank Thompson after his return from England.) They met up again by chance in 1979 on a street in Maroochydore, and Blackman wrote: ‘I loved the area and its climate and I loved meeting my friend James, who lived in an old wooden house right by the Maroochy River’.14 Birrell also introduced Blackman to the history and natural beauties of the region and encouraged him to explore the landscape, which would become a source of inspiration for Blackman’s art in the 1980s.

James Birrell’s enthusiasm for Charles Blackman as an artist was indicative of all of his Queensland contacts: regardless of vocation, they shared a deep appreciation and love of visual art and literature, and their mutual interests supported and fed Blackman’s creative process.

Endnotes

- Barbara Blackman, Glass After Glass: Autobiographical Reflections, Viking, Penguin Books Australia, Victoria, 1997, p.230.

- Blackman, p.110.

- Thomas Shapcott, Focus on Charles Blackman, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1967, p.15.

- Transcript of video interview with Meredith McKinney, National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, http://www.portrait.gov.au/stories/the-family, viewed on 25 May 2015.

- Betty Churcher, Molvig: The Lost Antipodean, Penguin, Ringwood, Victoria, 1984, p.92.

- Churcher, p.92.

- Laurie Thomas, The Most Noble Art of Them All: The Writings of Laurie Thomas, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1976, p.171.

- Churcher, p.69.

- William Hatherell, The Third Metropolis: Imagining Brisbane through Art and Literature 1940–1970, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2007, p.118.

- Pamela Bell served on the first Council of the Australian National Gallery for seven years and on the Board of the Queensland Art Gallery for four years. She published articles in Hemisphere, Art in Australia, and was art critic for the Australian newspaper.

- George Henry Johnston (1912–70), journalist and author, was best known for his autobiographical novel My Brother Jack (London, 1964). Hailed as a landmark Australian novel, it has been a great favourite with generations of Australian readers.

- Pamela Bell, letter to the Deputy Director, Queensland Art Gallery, date 28 January 1987, held in the QAGOMA Research Library.

- James Birrell, A Life in Architecture: Beyond the Ugliness, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2013, p.30.

- Charles Blackman and Al Alvarez, Rainforest, The Christensen Fund, MacMillan, Melbourne, 1988, p.4.

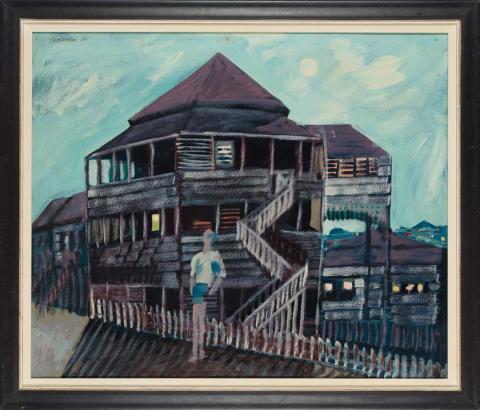

Feature image: Works by Charles Blackman on display in 'Lure of the Sun', Gallery 14, QAG, November 2015 / Purchased 1988 with funds from the Russell Cuppaidge Bequest as a memorial to Russell Cuppaidge CBE / © Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA

Connected objects

The Blue Alice 1956-57

- BLACKMAN, Charles - Creator

The bouquet 1961

- BLACKMAN, Charles - Creator

George Johnston c.1964

- BLACKMAN, Charles - Creator

Charles Blackman 1957

- MOLVIG, Jon - Creator

Related artists

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject