HAERIZADEH, Rokni; Subversive salami in a ragged briefcase...

Rokni Haerizadeh is an Iranian-born, Dubai-based painter and animator who has garnered international attention for his lyrical social critiques painted in a contemporary Persian miniature style. He began making art from a very early age, and later trained with renowned Iranian artist Ahmad Amin Nazar before completing a Masters degree in painting at the University of Tehran. These four acquisitions (each of which is titled Subversive salami in a ragged briefcase) are from Haerizadeh’s most celebrated body of work, ‘Fictionville’ 2009–ongoing, in which he paints over photographs and video stills of demonstrations, violent incidents and political events from the media. The individuals who originally appeared in these images are here transformed into surreal characters, emphasising the inherent elements of the grotesque within these real-life scenes.

Haerizadeh’s appropriation of political events and their reception in the media highlights the complexity of contemporary geopolitics and the way the media contributes to its convolution. The artist initially came to prominence for paintings that critiqued the lavish indulgences of the ruling class and religious clergy in Iran; since moving to Dubai in 2009 his focus has shifted to global politics.

One of the four works depicts a procession of human–beasts who are holding shrouded small figures dressed as the Egyptian gods Amun and Horos. The original image is of mourners in Gaza carrying two young Palestinian children Muhammad and Suhaib Hijazi who died in an Israeli missile strike.(1)

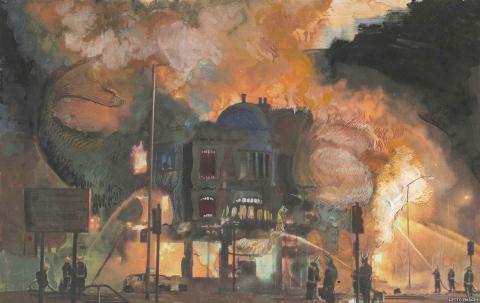

The second painting is of a hybrid mosque–sea creature ablaze, which appears to scream in anguish from its mouth–windows. Cow firefighters surround the beast, seemingly helpless against the flames. The work resonates in the Australian context where arson attacks on mosques have occurred around the country.

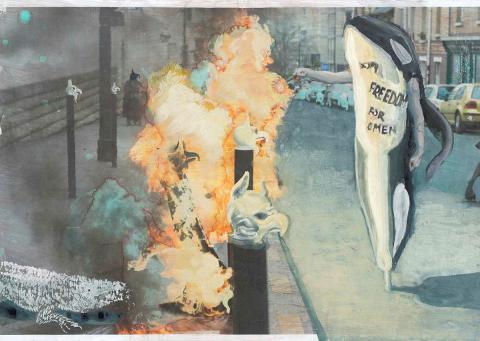

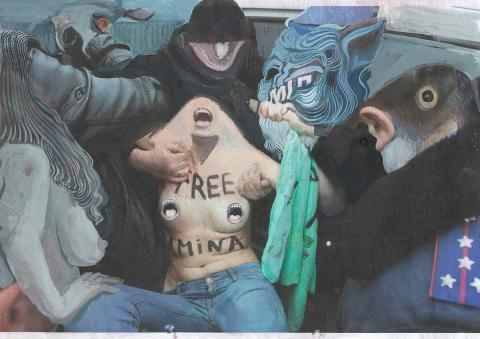

The remaining two works refer to the 2013 Paris iteration of an international day of protest, controversially called ‘Topless Jihad’ by the activist group Femen, held in solidarity with the arrested Tunisian Femen activist Amina Sboui (also known as Amina Tyler); in their attempt to ‘save’ Muslim women, Femen was criticised in the media and accused of playing up to colonial attitudes. In one painting, an orca with human arms and ‘freedom for [w]omen’ painted on its chest, stands on a blazing street, while a ghostly white crocodile cowers in the opposite corner. The other work captures a group of animals who surround a screaming figure with ‘FREE AMINA’ written on its chest.

These works contain many art historical references, including Goya’s frank depiction of the brutalities of war in the series of prints entitled ‘Los Desastres de la Guerra’ (‘Disasters of war’) 1810–20; JMW Turner’s The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons 1834; the surreal, beastly figures in Francis Bacon’s triptych of 1944, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion; and the tradition of Persian miniature painting. Haerizadeh is inspired by the rich history of social satire within Persian poetry, miniature painting and theatre, particularly in the golden era of Shiraz from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries. Arts writer Negar Azimi notes that the ‘Fictionville’ series has a more recent ‘spiritual ancestor’ in the Persian musical play Shahr-e Qesse (or ‘City of stories’, more commonly known as ‘Fictionville’) 1969–70. The play’s composer, Bijan Mofid (1935–85), used animals to critique society and power in order to avoid falling foul of the authorities. Its central character is an elephant with a broken tusk — an allegory for the fate of Iran — that a naive village community tries to help. Despite their good intentions, they disfigure him to an unrecognisable degree, and he is forced to assume a new identity.

Rokni Haerizadeh also transforms people into animals to point to the ‘animal instincts’ at work in large demonstrations and in acts of violence: ‘In my work, I am depicting people as animals not to dehumanise them, but rather to emphasise the dear beast inside all human beings’.(2)

Recent public discussion has pointed to a growing apathy towards violent imagery in the media; by transforming these images, the artist enables us to see them as if for the first time as well as drawing out the universality of many of their themes.

Endnotes

1 Swedish photographer Paul Hansen won the 2013 World Press Photo of the Year competition with this image; he was accused, and later cleared, of creating a composite image for political

reasons. See Stan Horaczek, 'Experts confirm "integrity" of 2013 World Photo Award winner', 15 May 2013, accessed 10 April 2017.

2 Artist quoted in ‘Rokni Haerizadeh’ by Naomi Lev in Artforum, 25 August 2014, accessed November 2016.

Ellie Buttrose, Artlines no.2, 2017, pp.52-53.