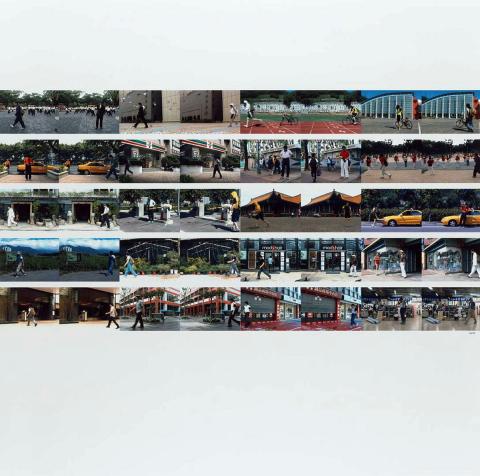

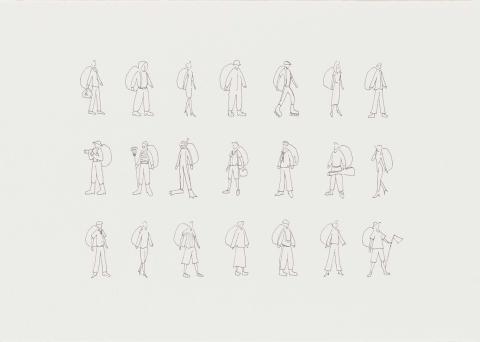

Tsui Kuang-Yu, The Shortcut to the Systematic Life (series), 2002-05

By Shihoko Iida

Artlines | 1-2011 | March 2011

Publisher: QAGOMA | Editor: Stephanie Kennard

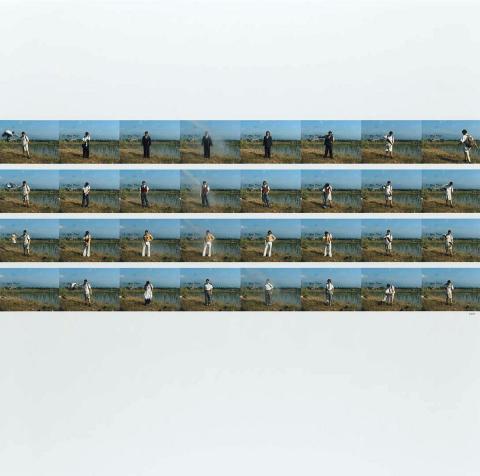

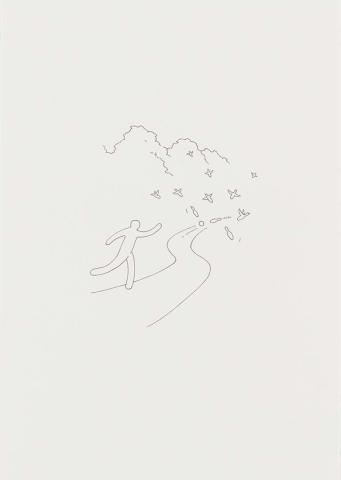

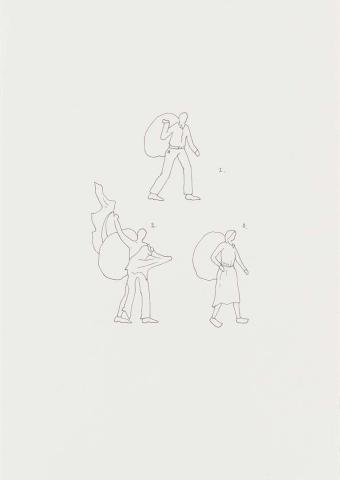

Tsui Kung-Yu’s video trilogy The shortcut to the systematic life consists of documentation of small social interventions by the artist. Perhaps these acts can be described as interjections by an anonymous individual, living in a homogenised city formed by universal urban architecture and structured by invisible social codes to which we all are bound. Each action performed by the artist looks ridiculous at first glance, but in fact is carefully designed to conflict with standard common-sense and unconscious, yet institutionalised, social behaviour. Playing golf in public spaces wherever there is a patch of grass, and bowling in parks using pigeons as ten-pins are things we do not usually do, as they are not regarded as appropriate. In one video, ‘Superficial Life’ 2002, for example, the artist’s constant masquerade using superficial one-sided uniforms in various locations mocks how we assimilate ourselves into a situation according to unseen conventions. Tsui performs his humorous actions as an ordinary, anonymous person. ‘What I want to deliver’, he says, ‘is the awakening of our daily life’.1

A crucial point of Tsui’s work is that he minimises the critical implications that his actions deliver, rather he emphasises their playfulness by using humour as a form of resistance. This enables him to connect with his audience, as each action he performs and records is simple enough to make us also want to try them, even if we do not actually do so. Yet his work is not only completed by mere actions, but also by the need to be recorded and replayed. Tsui describes himself as an ‘action artist’ rather than a video artist, and the accurate translation of the Chinese phrase ‘action art’ is ‘action recording’.2 His actions are performed, documented and replayed as a video work to communicate with viewers who witness them as a secondary experience.

Tsui’s work is made from the repetition and accumulation of simple actions in various locations within the fixed frame of the video camera, similar to a stage performance. He exits the frame at the end of each work so that the actions are viewed in a sequence, symbolising the repetition of daily life and allowing viewers to recognise that they also perform roles in their own lives, even if unconsciously.

Tsui’s restrained critical humour also carries traces of the dramatic history of post-war Taiwan, particularly the period after martial law was lifted in 1987. The rapid social and political shifts in Taiwan in the 1990s allowed Taiwanese artists to re-engage with Western art — previously prohibited under martial law — with contemporary art in Taiwan developing remarkably within a decade. Such a condensed history of contemporary art has impacted on the ‘Third Wave’ generation of Taiwanese artists who were educated after the end of martial law, including Tsui. This generation distances itself from the radical political ideologies embraced by artists of the first and second generations, and deals more with global issues, while identifying specific Taiwanese roots. It is as if the one-sided uniform Tsui wears as an artist is warning us that the idea of universality may lose specificity, resulting in superficiality.

Endnotes

- Tsui Kuang-Yu, ‘Tsui Kuang-Yu — the action artist’, in Culture Taiwan, 26 April 2007.

- Timothy Murray, ‘Thinking Electronic Art Via Cornell’s Goldsen Archive of New Media Art’, in NeMe: The Archival Event by Timothy Murray, Intelligent Agent, 2 June 2008.