PARDINGTON, Fiona; 'Ahua: A beautiful hesitation' series

‘I think everybody has a fantasy about being able to look at their ancestors.’ (1)

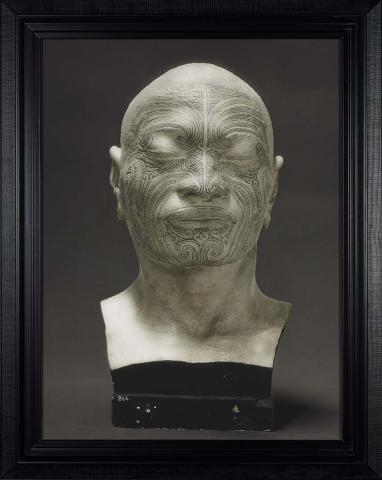

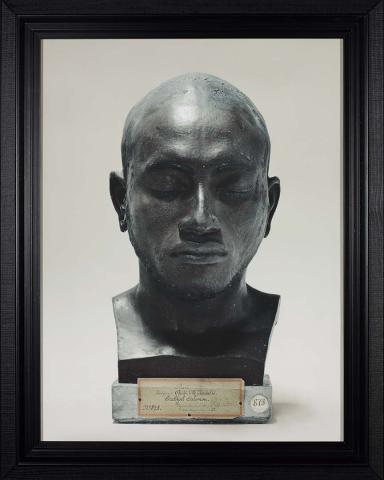

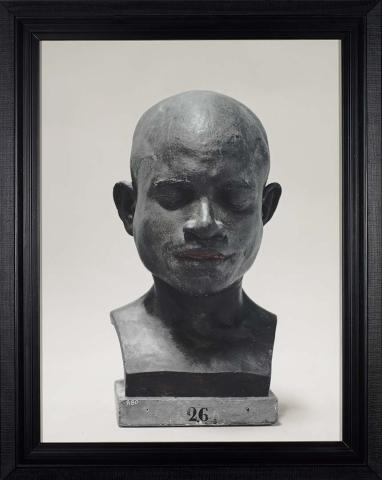

Pierre-Marie Alexander Dumoutier, aboard the ship of French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville, took over 50 life-casts on his 1837 journey to the Pacific. His casts recorded the likeness of different individuals he encountered (including Dumont d’Urville), as well as registering the growing importance of phrenology as a ‘science’ of race in nineteenth-century Europe. Created by covering the subject’s head in plaster of Paris, Dumoutier’s casts recorded, in intricate detail, specific facial features and head shapes. By studying and comparing these physical characteristics with those of other skulls, phrenologists like Dumoutier assigned particular traits and mental faculties to the ‘race types’ recorded.

Nearly two centuries later, Fiona Pardington has taken photographic portraits of these casts. Tracking them down in museums in New Zealand and France, she has flooded them with soft, warm light and clicked the shutter to capture the features of individuals long dead. The photographs have a powerful emotional charge, reminding us of the fast pace of time and our own place within it. Pardington enjoys the sense of contingency and photography’s direct invitation to the viewer to respond to its subject.

For Pardington, the ‘Ahua: A beautiful hesitation’ series has a particularly personal importance as some of the Maori depicted were known to her ancestors. As with her previous photographic series of taonga (Maori treasures) found buried in museum storerooms, the ‘Ahua’ life-casts are posed, lit and composed as intimate portraits. Understandably, many Maori and Pacific Islander peoples have developed a complex relationship to portraiture and Dumoutier’s life-casts. In talking about the life-casts Pardington has said that:

'Maori would say that the ancestors inhabit the ahua (life-cast) and that the ancestor had come from behind the greenstone veil and that they are here all the time, it’s just that we can’t see them.'(2)

‘Ahua: A beautiful hesitation’ focuses on the different cultural understandings of portraiture. Ahua is a Maori word for ‘appearance, likeness and character’, and Auckland Art Gallery curator Ngahiraka Mason explains that when you experience ahua you become aware of a shared humanity.(3) Pardington has added the words ‘a beautiful hesitation’ to suggest that her photographs momentarily freeze the march of historic time to allow for an experience of ahua to occur. The contrast between this encounter and the segregating objectives of phrenology for which the life casts were made, causes us to reflect on the limitations of scientific recording and the importance of art, memory and the passage of time in our understandings of who we are.

Ruth McDougall, Artlines 1-2011, p.35.

Endnotes

1 Fiona Pardington, and Virginia Were, ‘Catalogues of exoticism’, Art News New Zealand, Autumn 2010, p.52.

2 Fiona Pardington, pamphlet published on the occasion of the 17th Biennale of Sydney Biennale, Two Rooms Gallery, New Zealand, 2010, unpaginated.

3 Pardington, pamphlet.