UNKNOWN; Japanese ambrotypes

Ambrotypes became the predominant form of portrait photography during the great wave of modernisation in the late nineteenth century, and represent a significant place in Japanese photographic history. The Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) was a period of major transition in Japan in which the country changed from a relatively isolated feudal society to one governed by an imperial authority that encouraged greater economic integration and cultural exchange with the West.(1) The introduction of photography was one development which marked the changing nature of Japanese society at this time. In the port cities, souvenir photography became a bustling trade; hand-tinted photographs illustrating Japanese life and culture were bound in portable albums and sold as souvenirs to foreign visitors. The medium developed from a tourist-driven market to a thriving domestic industry in the latter part of the nineteenth century and a variety of photographic practices were adopted in ways that complemented the rich pictorial traditions of Japan.

Ambrotypes are an interesting part of this history as they were produced primarily for a local market, and although cheaper and more efficient to produce than albumen prints, they differ considerably from the photography produced for tourists.(2) Ambrotypes are a rare kind of glass photograph, and were commissioned as portraits of loved ones to commemorate birthdays, graduations and special occasions. They were held in family collections and passed down over time. Pocket-sized in scale, and encased in delicate wooden boxes, Japanese ambrotypes have a unique material presence. The presentation cases are crafted from a light-weight timber known as kiri (paulownia) wood, which was traditionally used to store objects such as hand scrolls, combs and paintbrushes. Some of the cases are personalised with inscriptions in elegant calligraphy, on the lid or the base, noting the name of the sitter, the date and in some instances, the name of the photographic studio.

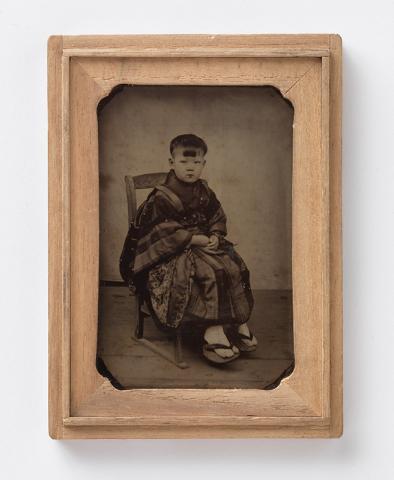

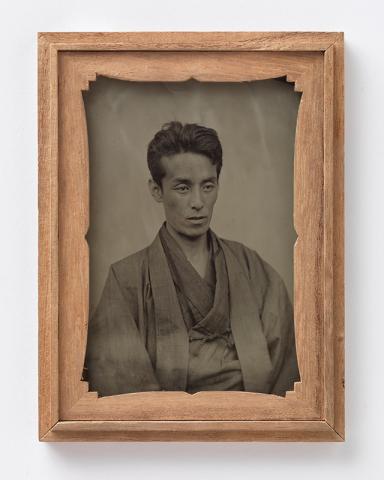

The earliest ambrotype in this group is the full-length study Portrait of young boy in traditional dress 1875. Seated on a wooden chair, the boy is dressed in an elaborate robe and has a distinctive hairstyle and, although positioned slightly on an angle, he looks directly at the camera. Other portraits are of Sakushiro Kato and Miwa Koshimune, taken at close range, with only the bust of their robes visible. The sitters’ eyes are slightly averted, which establishes a discernable distance between the viewer and the subject, and evokes a poignant and compelling narrative of the personal and unofficial stories in the history of Meiji-era Japan.

Mellissa Kavenagh, Artlines 3-2010, p.42.

The group of six Japanese ambrotypes purchased by the Queensland Art Gallery in 2010 includes: Portrait of Sakushiro Kato 1889, Portrait of Miwa Koshimune 1888, Portrait of young boy in traditional dress c.1875, Portrait of woman with owl figurine on table 1900, Young fashionable couple with their child c.1892 and Portrait of three young girls in their finest dress c.1870s.

Endnotes

1 From 1639 to Commodore Matthew Perry’s arrival in 1853, Japan had maintained relative political stability and autonomy, allowing only the Chinese and Dutch trading rights through a tightly controlled outpost in the Bay of Nagasaki. With the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the subsequent signing of treaties in 1858, the Japanese opened additional ports, and permitted foreigners to live and work in the ‘treaty ports’ of Yokohama, Nagasaki and Hakodate.

2 Peter C Jones, ‘Japan’s best-kept secret’, Aperture, vol.138, winter 1995, p.75.

Connected objects

Portrait of Miwa Koshimune 1888

- UNKNOWN - Creator