London Town (SICKERT, Walter Richard; STEER, Phillip Wilson; GREAVES, Walter; WHISTLER, James; VIRTUE, John)

As one of the world’s great cities, London has featured in the art and literature of the West like few others, with Paris as perhaps its only rival. Many works by William Blake, Gustave Doré, William Hogarth and JMW Turner derive from the city and its River Thames. Its political and social histories reside in the words of Shakespeare, Defoe and Dickens. It was the bustling human cargo of London’s streets that prompted Edgar Allan Poe’s The man in the crowd (1840) and its criminal intrigue brought us Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes.

Unlike Paris, London has been defined less by revolution than by political cunning, imperial treachery and mercantilism. It was razed by fire on several occasions and squalor, poverty and violence have been as much a part of its past as royal intrigue, its arts and letters and its fog. London did not undergo the vast redesign of its centre and surrounding districts that transformed Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century. The city of course saw extensive post World War Two rebuilding and recent urban renewal, but many areas unaffected by wartime bombing have retained their essentially medieval and labyrinthine qualities.

At the heart of London is its River Thames. As England’s major waterway and trade route, the Thames has occupied a unique place in the history and collective memory of London. It is at once a ‘sacred river’ as described by Peter Ackroyd in his 2007 book, Thames: Sacred River and a boisterous, industrial artery of commerce. The international trade and river traffic that characterised the river for centuries, however, has now been replaced with tourism and the hundreds of busy docks and warehouses have been transformed into architectural edifices of concrete, glass and steel.

A recent gift to the Queensland Art Gallery provides an opportunity to briefly look at Collection works by turn-of-the-century artists who worked and lived in London. Landscape no. 710 2003–04 by English artist John Virtue (b.1947), indicates the extent to which London remains a city which fascinates and draws artists to its history and particular urban topography. While this vast painting is a contemporary interpretation of London it somehow remains redolent of the complexity, mystery and atmosphere of this ancient city.

London and the River Thames feature in a number of Collection works — most prominently in paintings by Walter Richard Sickert, Walter Greaves, Philip Wilson Steer and etchings by James McNeil Whistler. The American-born Whistler was at the centre of a particular milieu in the city of London and is recognised as one the most influential artists of the late nineteenth century. His reputation is based largely on his painting but he was also responsible for a revival of the art of etching in England during the latter half of the nineteenth-century.

While in Paris during the late 1850s, Whistler developed a new approach to the technique of etching by using the copper plate in much the same way as a sketch book. He drew directly onto the plate, often en plein air, and retained the freshness of a drawing in the final printed edition. He produced the suite, 'Twelve etchings from nature' in 1858, which depicted scenes of urban Paris and surrounding countryside. In 1860 he settled in London and commenced a similar series titled 'Sixteen etchings of scenes on the Thames', commonly known as the ‘Thames set’. The choice of un-idealised, urban subjects, such as scenes of East End docks and derelict buildings, was unconventional and his loose, painterly treatment of the etching process also challenged the traditional use of the medium. Rotherhithe 1860 is one of the 16 etchings that comprised the ‘Thames set’ and depicts a then seedy dockside area of South London which had been a port and landing place since the medieval period. The influence of Japanese woodblock prints, which Whistler saw in Paris, is evident in the verticality of the composition which draws attention to the anecdote and incident of foreground.

Whistler had a number of followers and assistants which included both Walter Sickert and Walter Greaves. They called him ‘The Master’ and were to experience his notoriously prickly demeanour as well as his humour and generosity. Greaves met Whistler in 1863 and developed a close friendship with him, assisting in his studio and boating on the Thames where Whistler made studies and sketches for his nocturnes, the tonal, pared-back and moody paintings for which he is best known. Greaves was the son of a Chelsea boat-builder, Charles Greaves, who had in his time, taken JMW Turner on excursions on the Thames. Greaves and his brother Henry were both assistants to Whistler with whom they maintained a friendship until the late 1870s when Whistler’s popularity and reputation attracted new circles of friends and admirers. As an assistant and ‘pupil’, Walter Greaves had adopted Whistler’s tonal style of broadly painted, simplified scenes of the Thames and environs. This is evident in Thames, winter in the foggy greys, whites and blacks. Greaves exhibited similar works in an exhibition in 1911 at the Goupil Galleries, London resulting in accusations of plagiarism and passing off unfinished and re-worked works by Whistler as his own. Greaves’s reputation did not survive this attack and he descended into obscurity and penury, dying of pneumonia in 1930.

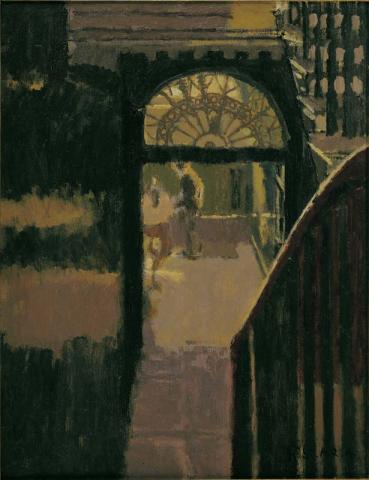

Sickert abandoned his short-lived formal art training at the Slade School in 1881 to assist Whistler in his London studio mixing pigments, preparing his palette and, together with Australian artist Mortimer Menpes, printing Whistler’s recently completed Venice etchings. Whistler taught primarily by example, and Sickert worked alongside him on many occasions. Whistler’s influence was eventually tempered after Sickert’s introduction to Edgar Degas and his work in 1885 and it is Degas’s influence on Sickert’s painting that is more evident in Whistler’s studio c.1915–17. The address, at 8 Fitzroy Street, was a room that Sickert kept as an atelier and had been Whistler’s studio in 1896. The view into a basement room is typical of the casually observed and fleeting vignettes that characterised Sickert’s urban naturalism.

While he spent periods living and working in the French city of Dieppe, Sickert’s depictions of prosaic, often dreary scenes of urban London and his early portrayals of its music halls defined him as an unconventional figure and a unique influence in early modern British painting. He declared London to be his inspiration and stated that

'. . . for those who live in the most wonderful and complex city in the world, the most fruitful course of study lies in a persistent effort to render the magic and the poetry which they daily see around them.’ (1)

Together with Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer was a member of the New English Art Club which, in the 1890s, was the progressive alternative to the Royal Academy. Sickert and Steer in particular were also referred to as ‘London Impressionists’. Steer observed and applied Impressionist techniques, particularly those of Monet, to a greater extent than other members of the group during the late 1880s and early 1890s. Steer’s Battersea Reach 1924 is characteristic of his loose, impressionistic brush technique and also owes much to the muted tonal palette of Whistler’s ‘nocturnes’. The small painting captures a glimpse of the London skyline and the Thames in a cursory, sketch-like manner, and anticipates the artist’s increasing preference for watercolour in later years before his eyesight began to deteriorate in 1928.

For contemporary artist John Virtue, the city skyline of London and its architectural monuments demanded a new approach from him when he took up his residency as associate artist at the National Gallery of London in 2003. As an artist, he was versed in the landscape of his native Lancashire and Devon, where he had worked during the 1980s and 90s. Virtue’s energy and enthusiasm for the robustness of urban London is redolent in the vigour of his treatment of the vast canvases that he produced during his residency, known collectively as the 'London paintings'. Landscape no. 710 is one of the largest in the series.

Virtue’s paintings developed in tandem with hundreds of drawings he made on daily walks in the city and from a few rooftop locations. They provided a collective template for memory, imagination and direct experience to determine, or at least guide, a very intuitive method. His paintings occupy an ambiguous zone between tradition and inventiveness, between the order of Rubens and the swirling tenor of Turner — a zone that Virtue recognised as fertile ground for developing this monumental series of works.

The spirit of Virtue’s London in Landscape no. 710 is more resonant of the city that Turner and Gustave Doré knew than the one Monet visited in the early 1870s and late 1890s. Here, its light is more crepuscular than Whistlerian nocturne, and the almost pugilistic intensity of Virtue’s heroic mark-making is intrinsically more cockney than Chelsea. For Virtue and many artists before him, the city of London provided a conduit to a past both grand and dark and a present that beats with a nervous, slightly twitchy but inimitable energy.

David Burnett, Artlines, no.1, 2010, pp.32–33.

This is the sixth article in a series focusing on selected works in the Queensland Art Gallery’s international collection.

Endnote

1 Walter Richard Sickert, London Impressionists [exhibition catalogue], The Goupil Gallery, 1889, p.6–7; quoted in Kenneth McConkey, Impressionism in Britain [exhibition catalogue], Barbican Art Gallery, 1995, p.50.

Connected objects

Battersea Reach 1924

- STEER, Phillip Wilson - Creator

Thames, winter unknown

- GREAVES, Walter - Creator

Rotherhithe 1860

- WHISTLER, James - Creator

Landscape no. 710 2003-04

- VIRTUE, John - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject