James Fairfax gift

By Emily Wakeling

Artlines | 4-2018 | Publisher: QAGOMA | Editor: Stephanie Kennard

‘A Fleeting Bloom: Japanese Art from the Collection’ includes ceramics, paintings, photography and sculpture that highlight an aesthetic of impermanent beauty, transitory moments and the natural world. Alongside works from the Gallery’s existing collection of Japanese art are several painted screens and hanging scrolls from the estate of James Fairfax, bequeathed to the Gallery in 2018. After a lifetime of collecting and philanthropy, Fairfax (1934–2017) was renowned for his distinguished art collection. His nephew Edward Simpson, director of the James Fairfax Foundation, gave some insight into his uncle’s love of Japanese art:

His first overseas trip in 1947, aged 14, was to Japan and it had a major impact on him, his cultural awareness, his developing taste, and collecting eye. Following a tumultuous few years, he returned to Japan in 1988, and again in 1990 … retreating to a 16th century Samurai house near Kyoto.(1)

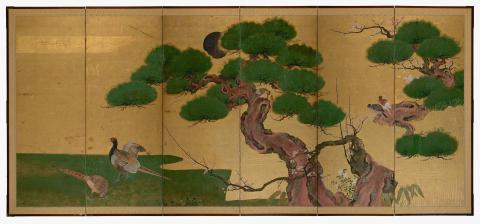

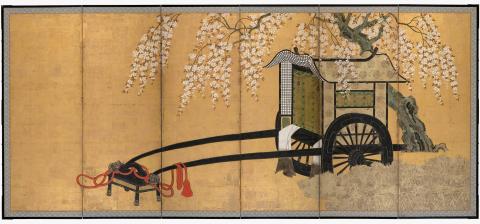

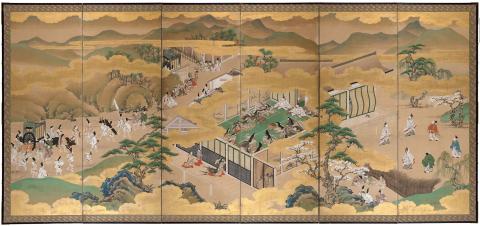

The historical Japanese works in this generous bequest were primarily acquired during Fairfax’s travels to Kyoto and Tokyo in the 1990s and 2000s. Among them are several byōbu (folding screens), a painting format that was at the peak of its production during the Edo period (1603–1868). Found only in the most wealthy homes and institutions, folding screens served a number of practical functions within the typically vast, open-plan audience halls characteristic of Japanese architecture of the period. Their wide, uninterrupted picture planes of the screens allowed artists to create ambitious landscapes known as shiki-e (two or more changing seasons in the same painting), in which animals, plants and other natural elements symbolise the transient seasons and their associated meanings in literature, poetry and other arts. Fairfax’s gift of a pair of Kanō School folding screens capture seasonal elements from all four seasons: the migrating birds of autumn; the evergreen pine of winter; the plum blossoms of early spring; and the rushing waters of summer. As well as being pleasing to the eye, the lightweight and portable nature of the screens meant that they were readily interchangeable according to the season or occasion.

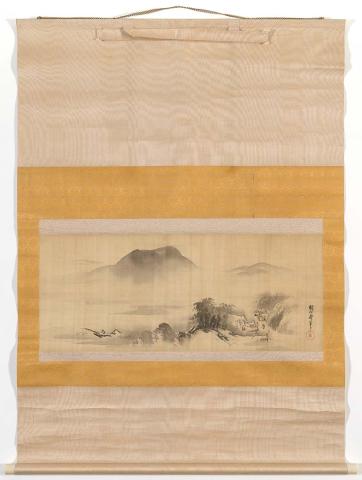

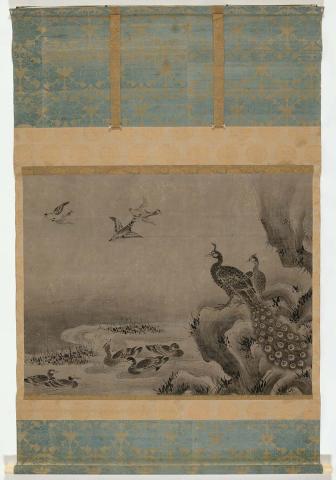

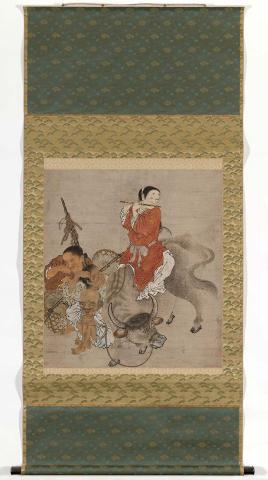

Kakemono (hanging scrolls) provide a more intimate expression of figurative painting, calligraphy and poetry, most often delivered in ink. They were typically hung in a tokonoma (alcove) of a private residence, tea house or temple, where images could be presented for worship or contemplation. The scrolls displayed in ‘A Fleeting Bloom’ depict a range of subjects, from symbolic animals and landscapes to illustrations of Zen Buddhist parables and expressive calligraphy. They often communicate a momentary sense of beauty and the impermanent nature of life — quite fitting for a form of painting that could be easily removed, rolled up and replaced to suit each context.

In addition to the recent acquisitions, the display also features earlier gifts from James Fairfax, including a pair of six-fold screens detailing the celebrated poets Li Bai and Lin Bu within mighty ink landscapes by Unkoku Toeki (1591–1644), and a narrow-necked jar from Tokoname, one of the famed Six Old Kilns of Japan. Donated by Fairfax in 1992, this clay stoneware is shown alongside ceramics from each of the other kilns — Seto, Bizen, Echizen, Shigaraki and Tamba — representing the most celebrated kiln sites of the Muromachi (1336–1573) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1568–1600) periods.

Inspired by Zen Buddhist philosophy, imperfections in these ceramics — such as the Tokoname jar’s elemental glaze — were later admired by patrons as being comparable to the beauty and uncontrollable elements of nature. The jar’s rugged appearance is enhanced by fly ash, a visual effect created when fragments from the kiln’s roof land on the surface of the object during firing. This fused to the pot as it touched the high-temperature silica components from the clay to produce the accidental glaze seen now.

These jars from the six kilns are complemented by other Japanese ceramics from the Gallery’s Collection, such as Edo period works by Buddhist nun Otagaki Rengetsu, whose restrained vessels are inscribed with poetry that reflects on sadness, loss, and life’s short-lived pleasures, often through the symbolism of nature and its changing seasons.

Finally, a collection of photography from the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912) captures a moment in Japanese history as new influences and technologies were beginning to interact with traditional life, and the nation was on the verge of social transformation that would signal the end of the ‘floating world’ culture of centuries past.

Endnote

- Edward Simpson, ‘James Fairfax’, Deutscher and Hackett, 30 August 2017, viewed August 2018.