ESSAY: Pierre Molinier's last session

By Sophie Rose

Artlines | 1-2021 | March 2021

Photographer Pierre Molinier was once dubbed the ‘magician of erotic art’ by the founder of Surrealism, André Breton. Molinier, although not famous in his lifetime, is increasingly recognised for his 1960s and 70s surreal photographic compositions of male and female flesh, nylon stockings and leather masks. The Gallery recently received three of his rare colour photographs through the generous donation of Alex and Kitty Mackay. These pictures invite us into the artist’s world, where mannequins, doll masks, and the most intimate parts of the body coexist, writes Sophie Rose.1

Warning: This article contains references to suicide that may cause discomfort to some readers. Lifeline Australia is available for 27/4 support on 13 14 11 or online.

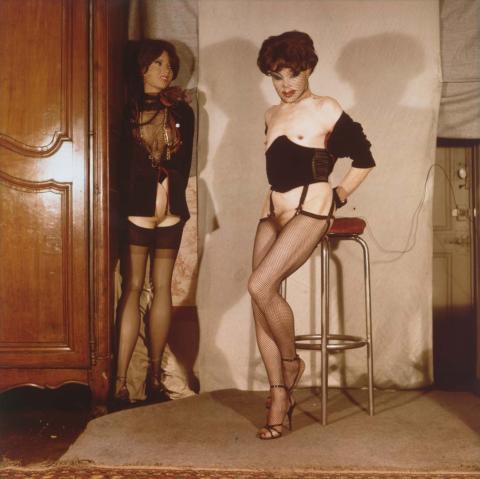

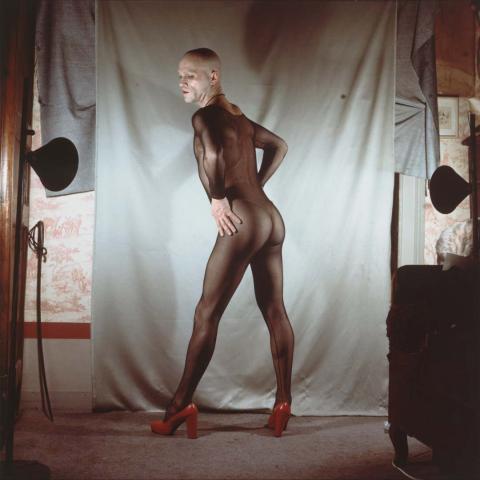

Although he began as a painter, some of the most striking images by French surrealist Pierre Molinier were captured by the camera. In a home studio, he took graphic images of himself and others that explored sexual fantasies or were rearranged into dreamlike collages. Very rarely did he use colour photography, except for a few images taken in the final years before his suicide in 1976. One of the last images ever taken by the artist shows a bald man in black lingerie, knee-high stockings and a headscarf, posed in a dim, makeshift studio. The figure embodies the paradox of the demure pin-up girl, echoing the tropes of post-war fantasies: he shyly lowers his gaze from the spotlights as a shawl slips from his shoulders to hang loosely from his wrists. In another photograph, the same man wears a sheer, head-to-toe mesh bodysuit and red heels — the mesh suit takes a fetish for black-stockinged legs to the extreme. Twisting his body into a sharp diagonal pose, we are reminded of the static limbs of a shop mannequin, or a fashion model contorted across an editorial spread.

The sitter in these two images is French artist Thierry Agullo. At age 74, Molinier befriended the 29-year-old Agullo, who shared his interest in erotic art, and invited him to collaborate in two photography sessions: the first was in March 1975 and culminated in a photo-essay in the magazine ArTitudes; and the second was in February 1976, only a few weeks before Molinier’s death. The Gallery recently accepted three rare colour photographs from this final series — two showing Agullo and one self-portrait — through the generous gift of Alex and Kitty Mackay. Each image represents a makeshift erotic space cordoned off from the outside world, as the artist’s dim Bordeaux apartment becomes the set to explore the human subconscious. Here, the real and the artificial synthesise to form an unusual kind of beauty, in which mannequins, doll masks, and the most intimate parts of the body coexist.

Once dubbed by André Breton as the ‘magician of erotic art’, Molinier is best known for his surreal photomontages. In 1955, his fledgling paintings caught the attention of Breton, by then renowned as the founder of the surrealist group that emerged in Paris in the 1920s. However, the good standing between the two artists only lasted for four or five years (apparently ending when Molinier sent a letter that even the avantgarde poet found too confronting) and his contact with the surrealists had fizzled by 1960.2 From the 1960s onwards, photography was his preferred medium, acting for him as both an erotic and aesthetic exercise. Although the historical line between an artistic, seemingly disinterested, nude and purely libidinal erotica is a slippery and often arbitrary one, Molinier’s images possess a dark intrigue that distinguishes them from other sexualised images. There is something compelling in his scenes that invites further attention. Freed from any fixed sense of self, his disguised sitters are like mannequins or dolls: ready to be taken apart, dressed in costumes, and joined by the artist in play.

In 1974, Molinier invited Agullo to play one such game. The first session took place on 14 March 1975 and was photographed by then medical student Michael Minard (under the alias ‘Monsieur Flash’).3 Of the 100 images taken that day, a small suite of black-and-white photographs were published in ArTitudes — a radical French art magazine begun by the critic François Pluchart — for the April–June 1975 ‘L’Indécence’ (Indecency) issue.4 The spread, which showed Agullo and Molinier helping each other dress in lingerie, was coyly catalogued as an ‘interview’ between the two artists. After the success of the ArTitudes series, they arranged a second photoshoot almost a year later in February 1976, this time on the theme of androgyny, featuring Agullo’s female alter ego, Thérèse. Molinier ordered garments made specially for Agullo and asked him to shave his entire body (including his head and eyebrows) in preparation.5 Initially, Michael Minard began to take black-and-white photographs as he had done the year before; however, in a burst of creative energy, Molinier soon began to photograph Agullo himself using a 6x6-inch slide, colour Yashica camera. Sadly, he would never see the final photos.6

As well as the two ‘Thérèse Agullo’ studies described at the opening of this essay, the Mackays’ gift includes an image of Molinier — the last in a lifetime series of erotic self-portraits. Veiled in his iconic doll mask, he wears only stilettos, stockings, a corset and shawl. He poses on a stool, genitals tucked between his legs, and holds a shutter release cable behind his back. Yet Molinier is not alone. In the left corner of the room rests a mannequin whose bottom half is turned the wrong way round, absurdly exposing a plastic cheek from beneath her black coat. It is believed, but not confirmed, that this was taken during his first session with Agullo in 1975, as the mannequin looks very similar to the ArTitudes photographs. Indeed, it is hard to distinguish the real person from his plastic approximate on first glance; Molinier might as well be a doll of his own creation.

The artist spoke often of taking his own life and had left matter-of-fact instructions for his tombstone. On 3 March 1976, he committed suicide. His note said, ‘I am finding living a terrible pain in the arse and I AM DELIBERATELY TAKING MY OWN LIFE and I think it’s a real hoot. I kiss all those I love with all my heart’.7 On the landing door outside his apartment, he had written ‘Died 19 h ½. For keys ask the notary Claude Fonsale’ (Fonsale was the concierge).

Molinier bequeathed the original Ektachrome transparencies to Agullo, but just four years later, Agullo himself died in a car accident. The slides were found in the wreckage and, deemed by the police as too indecent to pass onto his family, they were left to his friend, the gallerist and critic Jacques Donguy. Subsequently, in 1982–83, Donguy published five sets of 17 colour prints, each bearing the stamp of Francoise Molinier, the artist’s daughter from a marriage in his thirties. In 1994, Italian publisher Francesco Conz produced a new edition of 11 prints in a slightly larger format.8

At this time, Conz had a surprisingly strong connection to the Brisbane arts scene and was instrumental in building the Gallery’s holdings of contemporary art through several generous gifts. He championed the work of the Fluxus group: a radical movement of socially engaged artists in the 1960s and 70s who created cheap, ephemeral works to be disseminated en masse. Conz was a friend and collector of these artists and published special editions of their work from his house in Verona. In the 1990s, he began to sell through Brisbane art dealer Peter Bellas, and it was this connection that enabled the Mackays to purchase Molinier’s photographs.

Pierre Molinier was an outsider artist consumed with recreating his own image and, through his art, embraced his most deeply held fantasies. Decades later, his works continue to inspire new generations of artists as one of the many contributors to an evolving image of queerness.

Sophie Rose is former Assistant Curator, International Art.

Endnotes

1 With many thanks to Gael Newton AM for her thorough investigation into the work of Molinier and the artwork provenance. Her valuation research, conducted in June 2020, forms the foundation of this essay.

2 Maisie Skidmore, ‘The Forbidden Photo-Collages of Pierre Molinier’, Another Magazine (online), 12 November 2015, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/8019/the-forbidden-photocollages-of-pierre-molinier, 1 June 2020.

3 Jean-Luc Mercié, Pierre Molinier, Les Presses du Réel, Dijon, 2010, p.384.

4 ‘Interview, par Agullo et Molinier’, ArTitudes, nos 21-23, April-June 1975, pp.10-13.

5, 6 & 7 Mercié, Pierre Molinier, p.384.

8 Correspondence between Gael Newton and Jacques Donguy, 13 June 2020.