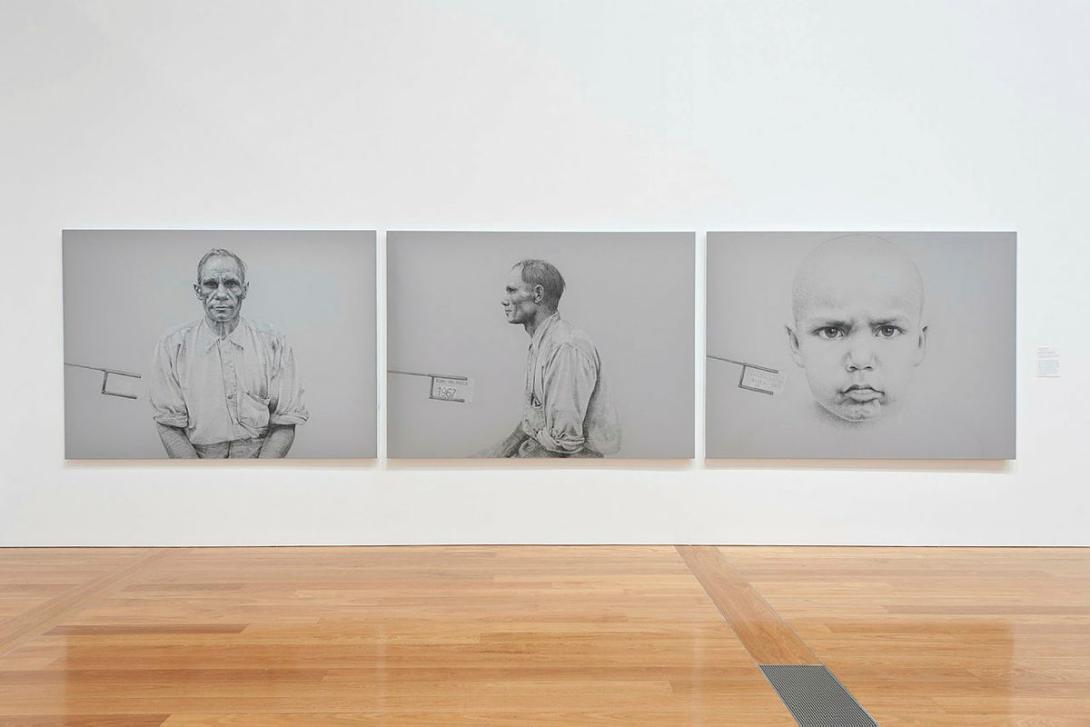

Across this large-scale triptych, Vernon Ah Kee has drawn portraits of his son and his grandfather, who appears on two of the three panels, accompanied by information on glass slides, as seen in anthropological photography. These historical portraits reference the work of anthropologist Norman B Tindale (1900–93) who, between the 1920s and early 1960s, photographed Aboriginal people from communities throughout Australia and recorded their genealogies. In 1974, Tindale published these images in his landmark study ‘Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits and Proper Names’.

While Tindale’s photographs are now available to the subjects’ descendants, the images themselves are often cropped for display in museums to minimise their clinical, ethnographic qualities. Ah Kee has explained that he wanted to interrogate this practice, and to transform the portraits into images that foreground the beauty and humanity of Aboriginal peoples, achieved by re-contextualising the images of his family from scientific curiosity to self-determined portraiture through the inclusion of language groups.

Vernon Ah Kee is a Brisbane-based Aboriginal contemporary artist who has risen to the forefront of urban-based conceptual art practice. This triptych is part of a series of large-scale hand-drawn portraits that the artist has been developing since 2004. These portraits have predominately been of male family members; each male relative’s portrait features a fixed glare, which directly engages the viewer.

Here, on two of the three panels, Ah Kee shows his grandfather in two views - profile and frontal - reflecting the practices used by the anthropologist Norman B. Tindale (1900-93) in taking historical photographs of Aboriginal people between the 1920s and the early 1960s. These are now supplied to their descendants as family portraits, and are often cropped to appear less anthropological.

The two panels featuring his grandfather also include a depiction of a glass slide, as per the historical records, with the language group and area attached. These read: ‘Waanyi Lawn Hill’. In the final image Ah Kee’s son takes the place of one of his older relations. Here, Ah Kee rejects anthropological ideas that Aboriginal people were destined to die out quietly, asserting the continuation of an Aboriginal presence through the portrait of his young son.