Daphne Mayo: A world of statues

By Michael Hawker

November 2011

The successful portrait sculptor, or painter for that matter, needs a front of brass, the hide of a rhinoceros, and all the guile of a courtier.1

Public and private commissions were Daphne Mayo’s financial mainstay throughout her long working life. By choosing sculpture as a career, Mayo was forced to depend on commissions rather than on exhibitions as her primary means of earning a living. This dependency produced master works of portraiture where she enjoyed a natural rapport with her sitter. Her finest portraits are insightful and sensitive depictions of layered personalities and singular characters.

Works by Daphne Mayo — including, seen from behind, Bust of Dr JV Duhig 1940, cast 1947 on display in Gallery 14, QAG, January 2012 / © Surf Lifesaving Foundation and The United Church in Australia Property Trust (Q.) / Photograph: R Fulton, QAGOMA

‘All my life I have lived in a world of statues’,2 declared Mayo in a letter to DM Fraser, while working on her statue of Sir William Glasgow in the early 1960s. In this letter, in attempting to convince the commissioning committee she had the experience for the task, she explained the enormously demanding nature of the casting process and the substantial costs involved. She required personal strength and excellent organisational abilities to bring her creations to fruition. Producing a bronze portrait involves multiple stages — first clay and plaster moulds are created, then a foundry mould is produced, and exacting skill is required as part of the pouring process in order to create the bronze cast. Great sculptors tend to be determined personalities with considerable reserves of stamina. Accordingly, Mayo’s qualities enabled her to complete many sculpture commissions and, despite the prevailing conservatism of the era, to also further the cause of art in Queensland.

We get some sense of the detail and precision involved in the portrait bust process in Mayo’s papers, which contain sophisticated preparatory diagrams of physical measurements, such as the notes for a portrait bust of Dame Mary Gilmore. Dimensions of eyes, nose and mouth, and the width of cheekbones and eyebrows, are plotted and scaled to aid the creative process and produce a lifelike portrait.

Mayo was inspired by the history of sculpture and, in particular, felt that ‘Renaissance art was extraordinarily human and many-sided’.3 Her portrait busts draw from this humanist tradition of sculpture, and emphasise the individual qualities of her subjects. One of her most accomplished works is the portrait bust of art dealer John Young, dated 1944,4 first shown in the ‘Three Sculptors’ exhibition, in Sydney in 1946. Mayo captures Young leaning slightly forward, as if he has just made a pertinent verbal point, or, alternatively, as if he is dreamily staring into the middle distance. Fellow artist Lloyd Rees considered it ‘one of the finest bronze portraits ever done in Australia’. In describing Young’s character, Rees said:

So much was mixed up in the man: he was realist and mystic, and a man of business as well. But he was hopelessly impractical when his heart was involved.5

Portrait of Lloyd Rees c.1944

- MAYO, Daphne - Creator

Blackie c.1943

- MAYO, Daphne - Creator

Mayo captures these traits with sensitivity and insight. She was extremely adept in expressing the core of a personality and this can be seen in portrait busts of Dr Christine Rivett, dated 1951,6 and Lloyd Rees, dated c.1944. Rivett and Rees were kindred spirits with whom she shared friendships and enjoyed mutual respect.

In the 1940s, Mayo explored new directions in portraiture, experimenting with the possibilities of form, but always in a restrained manner. Sparingly modelled portraits from this time reveal her interest in simplified proportions. In the portrait bust of Dr JV Duhig, dated 1940,7 the torso is reduced to a bulky, almost abstract form, clad in a medical gown, while the large thickset planes of the face are expressively rendered. Arms belligerently folded, Duhig’s imposing figure captures the sparkle of a keen intellect, and, when caught by the light, the moulded form of the bronze seems to twitch with life. In another commissioned portrait, a medallion of The Honourable W Forgan Smith for The University of Queensland, executed in 1942,8 the head in profile is reduced to a series of lines and angles capturing Forgan Smith’s distinct features and lending the powerful Queensland politician the aura of a Roman emperor.

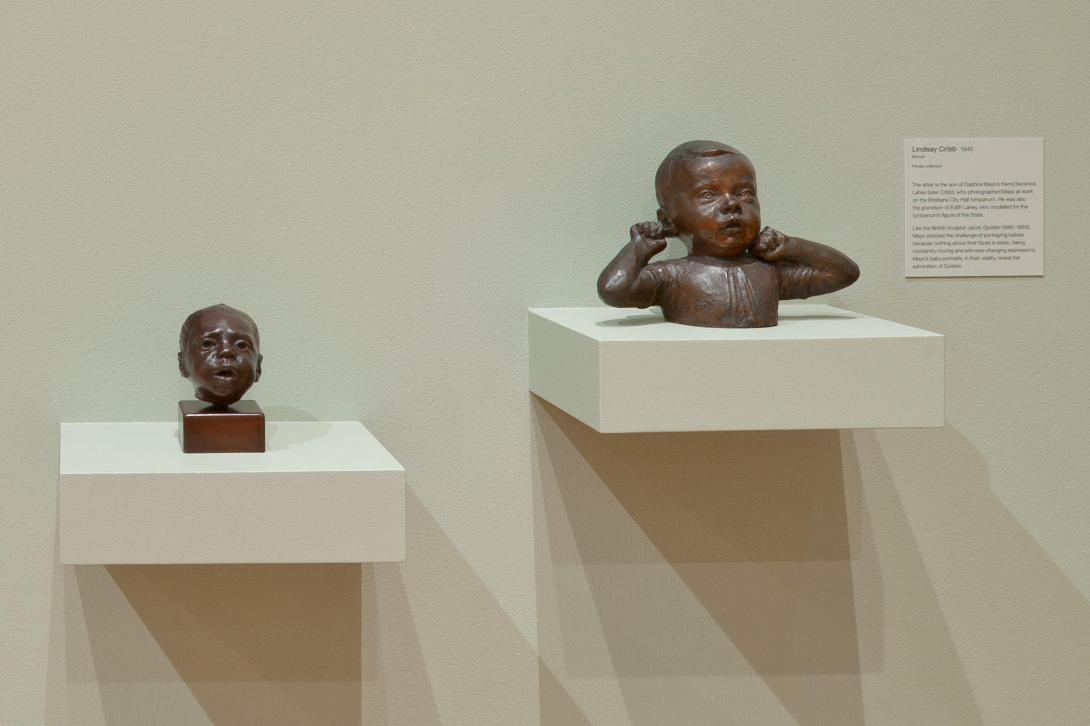

In the 1940s, Mayo also created several portraits of babies, such as Lindsay Cribb 1945. She acknowledged being challenged by the fleshy, fluid forms of a baby’s face.9 In these works, we see the influence of the English sculptor Jacob Epstein’s animated portraits of babies caught in arrested expressions and gestures, though she was less impressed by Epstein’s more controversial works which she termed ‘exhibitionist excesses’.10 In many ways, we can see these works as a set task so the artist could extend her mastery of the medium by attempting to capture the energy of the unformed features of a young child.

Daphne Mayo’s Blackie c.1943 and Lindsay Cribb 1945 (Private collection) on display in Gallery 14, QAG, January 2012 / © Surf Lifesaving Foundation and The United Church in Australia Property Trust (Q.) / Photograph: R Fulton, QAGOMA

Mayo’s later commissions depicting the posthumous military figures Field Marshal Sir Thomas Blamey and Sir William Glasgow are more problematic. Where she did not connect with her subject, the result, though technically proficient, lacks the qualities of her best work. Unable to work only with the aid of photographs, as she felt they lacked transient expression, she spoke of her struggle to achieve a likeness of Blamey in letters to her mother: ‘I work on him, then leave him for a while — then get back to him — hoping to surprise the secret of his likeness’. Through perseverance she was able to report in a subsequent letter: ‘I’ve just looked up from my paper and caught Blamey’s eye — I believe he is becoming more life-like!’11 Mayo’s last public commission was for a larger-than-life-sized statue of Sir William Glasgow, World War One hero and politician.12 Proving one of her most onerous commissions, she later said: ‘It was sheer hard work . . . I felt exhausted those three years I worked on it’.13 These works took their toll physically on Mayo in her later years, but, always ready for new challenges, she turned to painting, producing a number of portraits of friends as well as a series of self-portraits.

Daphne Mayo’s attitude is best expressed by a letter she wrote to a friend while working on the William Glasgow sculpture: ‘After this I don’t want to do any more commissions. I want to do ‘creative work and I am all geared for it’.14 A passionate advocate for art, Mayo’s strong spirit and thirst for discovery and expression kept her quietly active until the end of her life.

Self portrait 1952

- MAYO, Daphne - Creator

- Jacob Epstein, in Let There Be Sculpture: An Autobiography, Michael Joseph Ltd, London, 1940, p.88.

- Daphne Mayo, draft letter to DM Fraser, undated, Daphne Mayo Papers, UQFL119, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

- Daphne Mayo, The Story of Sculpture in Europe [radio talk], 21 April 1934, 4QG Brisbane.

- John Young (1880–1946) was a gallery director, art dealer and collector who co-founded Sydney’s Macquarie Galleries in 1925.

- Lloyd Rees, The Small Treasures of a Lifetime: Some Early Memories of Australian Art and Artists, Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1995, p.119.

- Dr Christine Rivett (1891–1962) was an active pioneer in the field of women’s health. A follower of British social reformer Marie Stopes (1880–1958) she advocated birth control and later specialised in gynaecology. The torso rendition of coat and blouse captures something of her reputation as a flamboyant dresser.

- Dr JV Duhig (1889–1963) was the first professor of pathology at the University of Queensland (1938–47), and founder of the Red Cross Blood Bank in Queensland. A nephew of Brisbane‘s Catholic Archbishop James Duhig, he became a president and patron of the Queensland Rationalist Society and an advocate of free speech and thought.

- William Forgan Smith (1857–1953) was Premier of Queensland (1932–42) and was Chancellor of the University from 1944 until his death in 1953.

- Daphne Mayo, Interview with Dr Judith McKay, 28 August 1978.

- Dr Judith Mckay, Daphne Mayo, Sculptor, Master of Arts Honours thesis, 1982, p.181.

- Daphne Mayo, letters to her mother, 22 March and 27 June 1957, Daphne Mayo Papers, UQFL119, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

- Sir William Glasgow (1876–1955) was one of two Australian commanders who, in April 1918, led the Allied recapture of the French village of Villers-Bretonneux, a feat that proved a turning point of World War One. The statue is now located in Post Office Square, Brisbane.

- Daphne Mayo, Interview by Susan Davies, Sunday Mail, 18 June 1972.

- Daphne Mayo, letter to Mary Porter, 22 December 1964, Daphne Mayo Papers, UQFL119, Fryer Library, The University of Queensland.

This essay was originally published in Daphne Mayo: Let There Be Sculpture, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2011.

‘Daphne Mayo: Let There Be Sculpture’

Nov 2011 - Jan 2012

Digital story context and navigation

Explore the story

‘Daphne Mayo: Let There Be Sculpture’

Nov 2011 - Jan 2012

Daphne Mayo: A world of statues

Read ESSAY

Daphne Mayo: A monumental career

Read DIDACTIC

Daphne Mayo’s legacy to QAGOMA

ReadRelated resources