ESSAY: ‘Plenty’

By Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow

Artlines | 2-2023 | | Editor: Stephanie Kennard

Cultural sensitivity warning

QAGOMA would like to respectfully advise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers that this essay, pertaining to the Collection Focus ‘Plenty’, contains references to massacres.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart envisions a path to Makarrata, or ‘coming together after a struggle’, via a process of truth-telling. In the exhibition ‘Plenty’, currently at QAG [until January 2024], Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow examines the complex truths, dreams and family stories represented by the Queensland Art Gallery’s founding bequest, as well as another very special gift.

![An installation view of ‘Plenty’, featuring the Gallery’s [Frame] 1959 by James Bourlet & Sons, London; and the 1860 Tower carbine rifle comprising Repatriation effort: this is not mine to bear 2016 by artist d harding (Bidjara/Ghungalu/ Garibal peoples) / Courtesy: The artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA An installation view in a dark room with gallery walls painted black; an empty gold frame on the wall, in the centre of the photo, frames the darkness; beneath it, a rifle is displayed in a glass cabinet.](/index.php/system/files/styles/wide/private/2023-10/QAG_G7-9_installationview_20230403_ccallistemon_011.jpg?itok=FrTgRlpc)

An installation view of ‘Plenty’, featuring the Gallery’s [Frame] 1959 by James Bourlet & Sons, London; and the 1860 Tower carbine rifle comprising Repatriation effort: this is not mine to bear 2016 by artist d harding (Bidjara/Ghungalu/ Garibal peoples) / Courtesy: The artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA

The QAG exhibition ‘Plenty’ is based on two groups of historical international paintings drawn from the Gallery’s Collection. Perhaps unexpectedly, these apparently gentle paintings can be traced to Australia’s early colonial period and the violent settler frontier. They are exhibited alongside works by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Eugene von Guérard, and Australian contemporary First Nations artists d harding and Jennifer Herd.

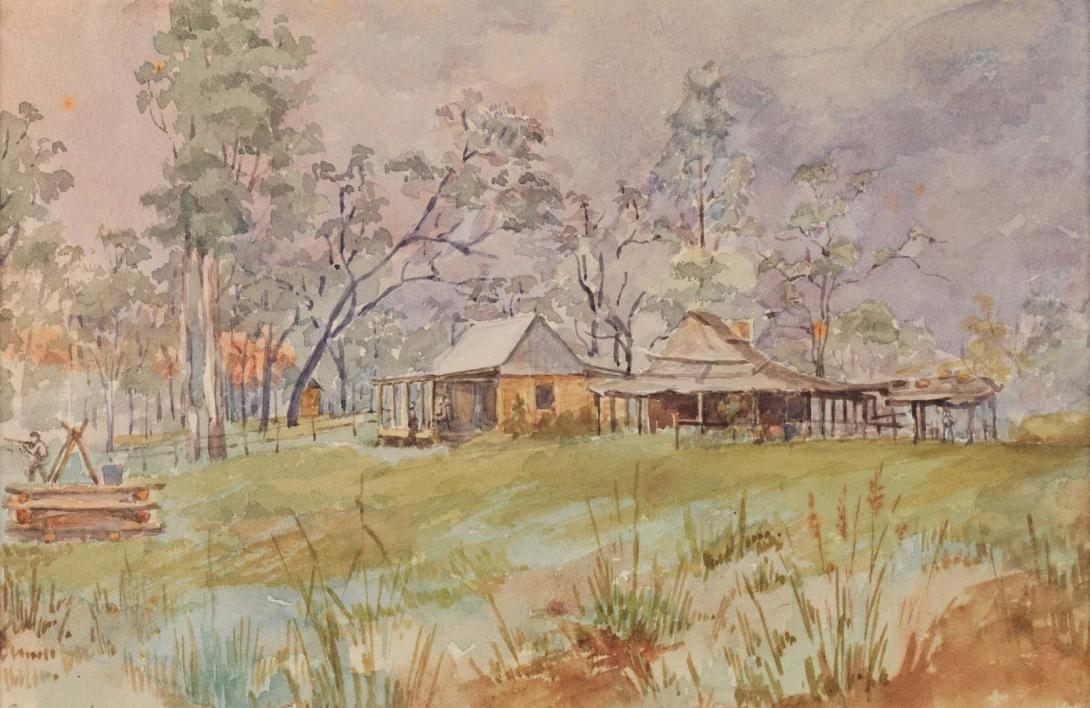

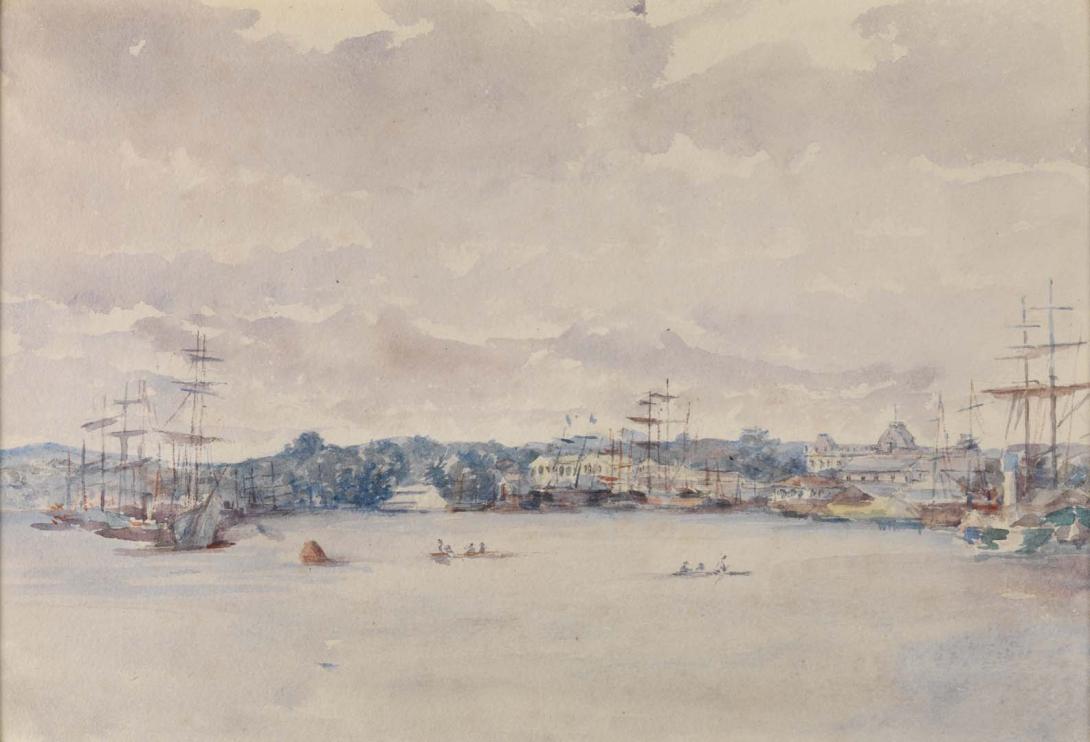

Two gifts are central. First, the Gallery’s founding bequest, made in 1892, from British settler the Hon. Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior MLC, of 11 Flemish and Dutch still-life paintings. These treasured works were offered to the new state of Queensland on the condition that a public gallery be created, so that they might be enjoyed by the wider community. And second, more than 70 years later, the 1964 gift of Major Clement Rolfe Ingleby in memory of his mother, Harriet Jane Neville-Rolfe, comprising 87 watercolours she painted while visiting family in Australia in 1883–84.

At first glance, both groups of paintings celebrate fertility and abundance. They feature fruit and flowers as well as moments of tenderness and nurture. We see images of mother and child; Neville‑Rolfe and her family seated for breakfast around a beautifully set table at Alpha Station; and the Holy Family, gathered around the Christ child, a basket of fruit at their feet. But there are also stories sitting just outside the frame of these works: they are haunted, in a sense, by the shadows of our colonial history — the dispossession, death and trauma experienced by First Nations peoples as newly arrived settlers sought to fulfil their dreams, to create a life of ‘plenty’, and sustain their own families.

This period of change is vividly described in Neville-Rolfe’s delicate watercolours: the clearing of land and breaking-in of horses, and in her noticeably more tentative sometimes unfinished portraits of First Nations peoples. These works are tender and emotionally real. Unlike her popular Breakfast, Alpha 1884, these watercolours have rarely been exhibited.

Created some two hundred years earlier, during the Flemish and Dutch ‘Golden Age’, Murray-Prior’s bequeathed paintings do not directly depict First Nations peoples’ dispossession and suffering; they carried their celebrations of tenderness, abundance, and Christian moral behaviour, long before their arrival in Australia. Their surprising place in our colonial history has been documented through the work of art historian Dr Kerry Heckenberg.1 The paintings travelled with Murray-Prior over the course of his life, including his time at Hawkwood (Ngarin) Station in Queensland’s remote Upper Burnett. While there, eight members of a neighbouring settler family, the Frasers, were killed, together with four servants. Murray-Prior rallied other local settlers in response. Over the following weeks, his group pursued the Jiman and other neighbouring First Nations peoples. They were subsequently joined by the Native Police, settler-commanded units of largely First Nations men, often violently forced into service away from their own Country. Hundreds were hunted down and killed in response to the Fraser family deaths alone. The sites of many of these massacres are documented and mapped.2

An installation view of ‘Plenty’: Still life c.1650 by Alexander Coosemans; Madonna and Child encircled by roses c.1650s by Jan van Kessel the Elder; and Madonna and Child encircled by flowers and fruit c.1615, attr. to Andries Danielsz / Bequest of The Hon. Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior MLC 1892 / Collection: QAGOMA / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA

Fleeing, Jiman sought refuge on neighbouring Country, including that of the Bidjara people. Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal artist d harding’s contribution to the development of this exhibition has been vital. This is a painful history: Frontier massacres, and the operations of the Native Police, had a profound impact on harding’s family. ‘Plenty’ features harding’s 2016 artwork Repatriation effort: This is not mine to bear (pictured at top of page), as well as the work of harding’s teacher, senior Mbarbarrum artist Jennifer Herd. In the tradition of the readymade, harding repurposes a carbine rifle once used by the Native Police, bearing the ‘VR’ (‘Victoria Regina’) stamp of Queen Victoria, and asks us to consider this history anew. Murray-Prior’s founding bequest carries both the aspirations and the pain of this critical period of our history, which haunts us still. ‘This is not mine to bear’, says harding. Can we work together to find ways to hear and bear the many stories that make up our larger history?

![An installation view of ‘Plenty’, featuring the Gallery’s [Frame] 1959 by James Bourlet & Sons, London; and the 1860 Tower carbine rifle comprising Repatriation effort: this is not mine to bear 2016 by artist d harding (Bidjara/Ghungalu/ Garibal peoples) / Courtesy: The artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA An installation view in a dark room with gallery walls painted black; an empty gold frame on the wall, in the centre of the photo, frames the darkness; beneath it, a rifle is displayed in a glass cabinet.](/index.php/system/files/styles/wide/private/2023-10/QAG_G7-9_installationview_20230403_ccallistemon_007.jpg?itok=2DDUGu8A)

A view of ‘Plenty’, featuring a glimpse of the Gallery’s [Frame] 1959 by James Bourlet & Sons, London; and the 1860 Tower carbine rifle comprising Repatriation effort: this is not mine to bear 2016 by artist d harding (Bidjara/Ghungalu/ Garibal peoples) / Courtesy: The artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane / Photograph: C Callistemon, QAGOMA

The improbability of Murray-Prior’s grand paintings appearing on the Australian settler frontier, as noted by Kerry Heckenberg, inspired the ‘Plenty’ exhibition, as did her reference to the writings of Murray-Prior’s daughter, novelist Rosa Praed. Over the period 1854–59, the paintings adorned the parlour of the family’s simple home, which Praed remembers as a hut, ‘built of slabs, with gaps between them, windows without glass and mostly earthen floors’.3 These precious paintings mostly hung unframed. Another account describes ‘slots cut in the slab walls through which . . . a rifle could be used for protecting the inhabitants’.4 She reflects that the paintings would 'have puzzled the stranger who came within our doors, to whom they must have seemed ludicrously out of keeping’.5 Praed was just six years old in 1857, when the Fraser family were killed and the subsequent violence against the Jiman.

The Gallery currently holds nine of the eleven paintings originally left to the new state of Queensland by Murray-Prior. He moved on from the Upper Burnett after the killings, and through his role as Post-Master General became a longstanding member of Parliament. By the time of his death in 1892, he had fathered 20 children. In 1895, when the Gallery opened as the Queensland National Art Gallery all the paintings were exhibited including two works: Father Time and Gethsemane. We no longer hold either painting, nor do we have any formal trace of their removal from the Collection. They are represented in ‘Plenty’ by an empty frame. The subject of ‘the missing’, of course, extends beyond these two paintings.

‘My father’s love for his pictures taught me to regard them with a sort of veneration, almost as though they were living things’, wrote Praed.6 She describes how, in later life, Murray-Prior often studied Father Time, ‘with his skeleton and hour-glass’:

[Father Time] looked down upon us with such deep, earnest sadness, that I felt sure there must be something in our mode of proceedings which troubled him. I wondered that my father, who often studied the picture, was not more oppressed by the disapproving gaze. Time held in his hand a scroll bearing a Latin inscription, which I was told came from the Bible, and I jumped to the conclusion that it was the commandment ‘That shalt not kill,’ and that he was grieving over its transgression.7

In art and literature, Father Time (or Chronos) was often portrayed with the ancient Roman proverb Veritas Filia Temporis — which translates to ‘Truth is the daughter of Time’. Perhaps in some instances, truth requires the passage of time. Today, we seek a truth-telling, and continue to dream of an Australia of peace, plenty and generosity.

‘Plenty’ is on display in Galleries 7 and 9 of the Philip Bacon Galleries, QAG, until 28 January 2024.

Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow is Curatorial Manager, International Art. She is of Irish, English and Māori heritage (Ngāpuhi iwi, Te Hikutu and Ngāi Te Rangi hapū).

Endnotes

- Kerry Heckenberg, ‘A taste for art in colonial Queensland: The Queensland Art Gallery Foundational Bequest of Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior’, Queensland Review, vol.25, no.1, 2018, pp.119–36.

- Refer to the University of Newcastle’s ‘Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788–1930’, https://c21ch.newcastle. edu.au/colonialmassacres/ and https://www.theguardian.com/ australia-news/ng-interactive/2019/mar/04/massacre-mapaustralia-the-killing-times-frontier-wars

- Rosa Praed (as Mrs Campbell Praed), Australian Life, Black and White: Sketches of Australian Life, Chapman and Hall, London, 1885, pp.31–2.

- HS Bloxsome, ‘The discovery, exploration and early settlement of the Upper Burnett’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, vol.3, no.5, 1945, p.344.

- 6. & 7. Praed, Australian Life, pp.38–40.

Find out more

‘Plenty’

Jun 2023 - Jan 2024

ESSAY: The Bequest of Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior

Read story

DIDACTIC: Harriet Jane Neville-Rolfe

Read storyDigital story context and navigation

Related resources