I have loved: Slowing down history

By Grace Jeremy

‘I have loved/I love/I will love’ August 2025

Content note: These works contain references to the impacts of war.

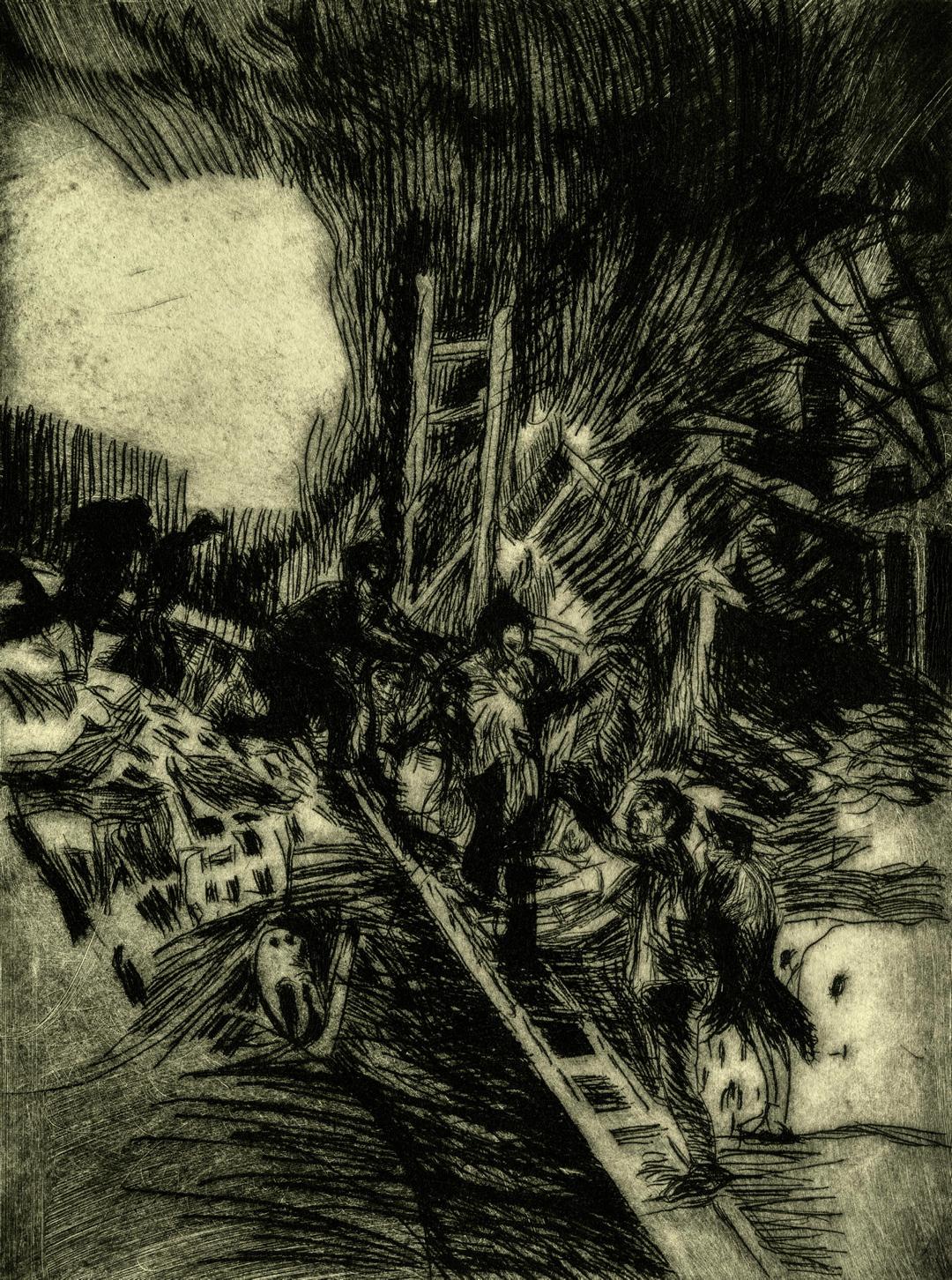

For over five decades, Pat Hoffie has explored themes of power and global politics through the lens of human experiences in her interdisciplinary arts practice. Her exhibition, ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’, presents her first extensive body of work in printmaking as an immersive installation. Enveloping the gallery space, her large-scale prints face towards a cluster of precarious ladders assembled in a vortex, so that together, they speak to the chaos and fragility of our contemporary life. Hoffie’s prints draw inspiration from a long line of artists who have used the medium to respond to the human consequences of war and conflict. Over the challenging year of 2024, she transformed scenes she witnessed in the media and committed them to paper; through this, she seeks to encourage the slow viewing and sincere contemplation of these often fleetingly glimpsed images.

Pat Hoffie / Australia QLD b.1953 / Image from ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’ 2025 / Giclée print on paper / Courtesy and © Pat Hoffie / Photograph: Nina White

The conceptual foundation of Hoffie’s prints can be found in a long history of conflict represented in printmaking in the work of artists such as Jacques Callot (France, c.1592–1635), Francisco Goya (Spain, 1746–1828) and Käthe Kollwitz (Germany, 1867–1945). Callot’s Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War) 1633 is commonly regarded as one of the first series of its kind to document the horrors of war and its effects on ordinary people. Produced against the backdrop of widespread political turbulence in Europe due to the many conflicts of the Thirty Years War (1618–48), across eighteen small plates the series follows the impacts of a group of soldiers who stray from their orders to commit crimes against local villagers before being caught and executed. Callot often places the dead and dying close in the foreground of his small plates, centring the viewer on the ultimate cost of war that is the loss of human life. According to curators and art historians Antony Griffiths and Hugo Chapman, ‘[Callot’s] humanity allowed the viewer to empathise with his tiny creatures, and experience the shock of discovering the terrible things that are happening’.1

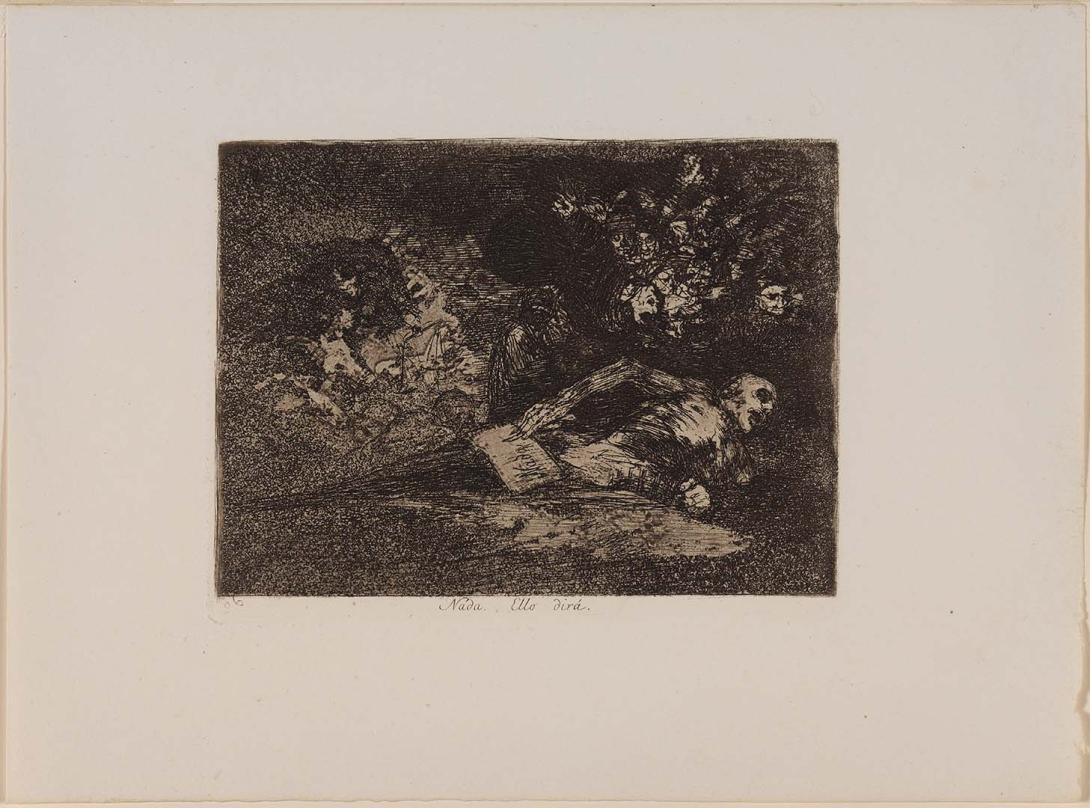

Callot’s emphasis on the harsh realities of conflict echoes in Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s series of 82 prints that make up Los desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) 1810–20. Published in 1863, 35 years after Goya’s death, the Disasters were likely inspired by events in Spain stemming from the Napoleonic Invasion and Peninsular War (1808–14) that the artist learned of through written reports or witnessed firsthand.2 In contrast to Callot’s narrative sequence, Goya’s series is a collection of discrete vignettes that focus on the harrowing circumstances of single groups of anonymous figures in desolate landscapes. The ravages of war are shown in unflinching detail, with Goya depicting prisoners being executed, civilians under attack, mounds of dismembered corpses, and people grieving for their companions who lie starving and dying. Two hundred years after its creation, the Disasters remains notable for its shocking and unsanitised account of the cruelty of war, while also showing moments of humanity in ‘the instinct for survival’ and ‘the desire for dignity’ in the face of these circumstances.3

Decades later, noted German artist Käthe Kollwitz also conveyed moments of humanity amid the horrors of war, most famously in her print cycle The Peasant’s War (1901–08). A politically engaged artist whose practice centred the working class, Kollwitz created these prints after reading literary accounts of popular uprisings in Germany in the sixteenth century.4 The seven bold, graphic etchings that make up the series are dedicated to the plight of a group of workers who lead a failed revolt. The initial prints portray the oppression the peasants are subjected to, which leads to their violent rebellion in the middle of the series, where frenzied groups of figures charge forward in battle. The series ends sombrely in its final plates: the sixth depicts a mother searching among corpses on a battlefield, while the final sheet shows a group of survivors tied up awaiting their execution. Centring on the anguish and grief of the peasants, The Peasants’ War ‘emphatically calls on viewers to empathise with their sufferings’.5

Hoffie falls within this history as another artist who uses print to grapple with representations of war and to foster compassion for those caught in its crossfires. Like Callot, Goya and Kollwitz, she focusses on the experiences of ordinary people involved in events of international significance — a consistent thread throughout her broader practice. With thousands of pictures at her disposal to choose from, Hoffie was drawn to those that represented moments of humanity among turmoil. An enduring theme is one of love, which is aptly reflected in the title of her exhibition. Hoffie’s works depict groups of figures fleeing danger, survivors being rescued from the wreckage of buildings, family members grieving and people helping each other. Images showing ladders used in dangerous rescues are echoed in her central sculptural installation, in which ladders emerge from rubble and reflective pools and stretch towards a black void in the gallery ceiling — a seemingly precarious structure over an unstable ground, representing destroyed environments and uncertain futures. Hoffie’s ladders also perhaps act as a metaphor for a ‘ladder of history’ – one that is not however an ascension towards ‘progress’, but rather a continuation of chaos, with her work epitomising another chapter in a long line of artists striving to make sense of our tumultuous world. Describing the lasting influence of her art-historical predecessors such as Callot, Goya and Kollwitz, Hoffie writes:

The graphic power of these artists’ works has long staked out turf in my brain. Simultaneously skilful, yet crude and cruel; historically specific yet somehow eternal, these images still manage to perform as anchor points capable of pinning this present moment to those of the past.6

Käthe Kollwitz / 'Battle Field', sheet 6 of the cycle Peasants’ War 1907 / Line etching, drypoint, aquatint, sandpaper and soft ground with imprint of ribbed laid paper and Ziegler's transfer paper, Kn 100Xb / Collection: Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Köln

Pat Hoffie / Australia QLD b.1953 / Image from ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’ 2025 / Giclée print on paper / Courtesy and © Pat Hoffie / Photograph: Nina White

Indeed, the work of these artists links Hoffie’s work to a broader history. This connection emerges through a common subject, but also through a shared visual language in the distinctive, graphic quality inherent to certain kinds of printmaking. Hoffie’s prints, with their scratched lines and areas of undecipherable blackness, have immediate visual similarities with various etchings and engravings throughout art history. Placed side by side with Goya’s Disasters, a cursory glance might lead Hoffie’s drypoints to look as if they are from the same ‘era’. In the words of the artist, ‘they look old, but they’re not. They’re happening now’.7

Although they are richly informed by art history, Hoffie’s prints are indivisible from the twenty-first century context she creates them in. This context sees images made, disseminated and consumed with an abundant frequency. While the reproducibility of print allowed illustrations of the impacts of war by artists like Callot, Goya and Kollwitz to be seen by wide audiences before news was endlessly delivered on multiple platforms and screens, Hoffie begins with imagery that already saturates the contemporary digital landscape. Her prints transform pictures from global conflicts she witnessed throughout 2024 on the nightly news, social media and news websites. The constant online documentation of war during this time meant that she found this imagery inescapable. The artist states:

I just couldn’t move away from the images that haunted every aspect of life during [2024] … Images that were incredibly challenging and harrowing became instantly forgotten as they were replaced by the mounting rubble of the next day’s image-onslaught. And the next and the next.8

Disturbed by how quickly these confronting pictures of suffering were consumed and discarded, Hoffie sought ‘to decelerate them’, writing ‘though each [image] shocked and sickened me, I could all-too-easily instantly forget them. And yet, it occurred to me, I had never been able to un-see a Goya’.9 For Hoffie, following the precedents of art history and harnessing print as the medium to consider this imagery provides the means for such ‘deceleration’.

Grace Jeremy (Assistant Curator, Australian Art), curator of ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’, at the exhibition opening on 31 August 2025, QAG / Photograph: K Bennett, QAGOMA

The physical making of Hoffie’s prints also embodies an initial act of ‘slowing down’. While the digital images that are her source materials are created and disseminated quickly, printmaking, on the other hand, is a lengthy process. Hoffie engages in the sequential processes of traditional printmaking methods: For the drypoints, she begins by laboriously incising images into small, lightweight acrylic plates using an etching needle. The plates are then inked and printed to make impressions on paper. To create the monoprints, Hoffie draws directly onto paper laid above a thin layer of ink. The images resulting from both methods become digitised again when Hoffie scans and reprocesses them before they are printed again at large scale. While the pictures Hoffie adapts would normally flash up briefly on televisions, computers and mobile phones, her prints hold space on the gallery wall — the largest spanning several metres and rendering the scenes within them close to life-size. Her original small markings become bold lines and gestures through which figures and landscapes are subsumed, entangled and then revealed. Hoffie’s images invite the viewer to contemplate them slowly and empathise with those depicted within, unfolding themselves to their audience through attentive and repeated viewings.

In this way, ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’ proposes that the slow-viewing encouraged by art museums provides an antidote to the fast-paced viewing of the digital era. Hoffie cites art critic, media theorist and philosopher Boris Groys, who proposes that the art museum plays a vital context for the critical interpretation of images in the twenty-first century at a time when the mass media plays a dominant role in their dissemination. According to Groys, writing in 2006, due to ‘the current cultural climate, the art museum is practically the only place where we can actually step back from our own present and compare it with other historical eras’.10

For Hoffie, galleries are spaces where pictures can be carefully analysed and considered amid social contexts of immediacy and increasing polarisation, and places where art wrestles to retain its capacity to convey moments of humanity and compassion in the face of the horrors of war. In today’s overwhelming digital landscape, Hoffie encourages the slow viewing of conflict imagery by translating it to print through traditional, time-consuming processes that intertwine the analogue and the digital. In an era where visual stimuli are rapidly disseminated, consumed, discarded and forgotten, Hoffie endeavours to shift the relationship between viewer and image, asking us to solemnly pause in front of those trapped within the throes of war.

Grace Jeremy is Assistant Curator, Australian Art, QAGOMA.

- Antony Griffiths and Hugo Chapman, ‘Israel Henriet, the Chatsworth Album and the publication of the work of Jacques Callot’, Print Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, 2013, p.280.

- Janis Tomlinson, Francisco Goya y Lucientes, 1746–1828, Phaidon Press, London, 1994, p.193.

- Juliet Wilson-Bareau, ‘Goya: The Disasters of War’, in Disasters of War: Callot Goya Dix [exhibition catalogue], National Touring Exhibitions, Hayward Gallery, Arts Council of England, London, 1998, p.37.

- Hannelore Fischer, Käthe Kollwitz: A Survey of Her Works 1888–1942, Himmer, Munich, 2022, p.90.

- Fischer, p.95.

- Pat Hoffie, artist's statement for ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’, 2025, QAGOMA Collection Online.

- Pat Hoffie, artist's statement for ‘MMXXIV’, 2024.

- Pat Hoffie, interview with Grace Jeremy, Artlines, no. 3-2025, QAGOMA, September 2025, pp.24–9.

- Pat Hoffie, exhibition essay for ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’, QAGOMA Collection Online.

- Boris Groys, ‘The politics of equal aesthetic rights. Dossier: Spheres of Action – Art and Politics’, Radical Philosophy, no. 137, 2006, p.32.

Explore ‘I have loved/I love/I will love’

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEPat Hoffie: I have loved/I love/I will love

Read ESSAY

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEPat Hoffie: Only scratching the surface

Read ARTIST'S STATEMENT

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEInk impressions: Pat Hoffie’s printmaking

Read INTERVIEWDigital story context and navigation

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEExplore the story

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEPat Hoffie: Only scratching the surface

Read ARTIST'S STATEMENT

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEPat Hoffie: I have loved/I love/I will love

Read ESSAY

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEI have loved: Slowing down history

Read ESSAY

Digital Story Introduction

I HAVE LOVED/I LOVE/I WILL LOVEInk impressions: Pat Hoffie’s printmaking

Read INTERVIEW