Meet the drovers (3)

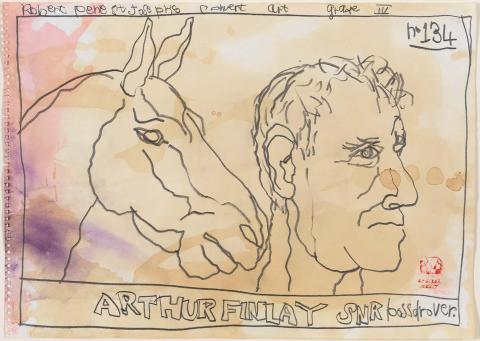

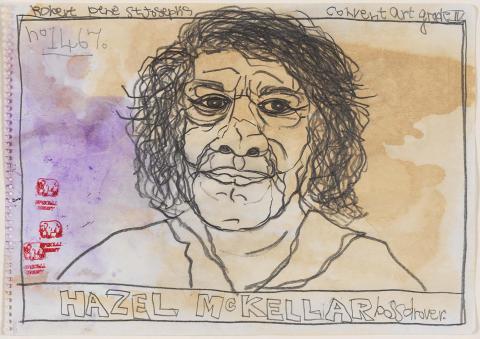

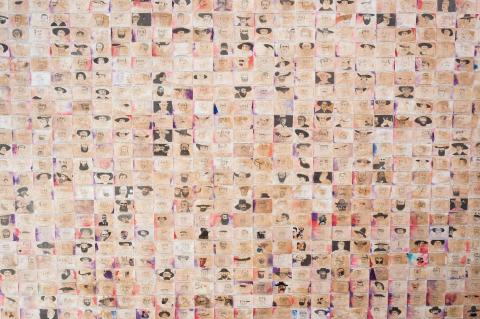

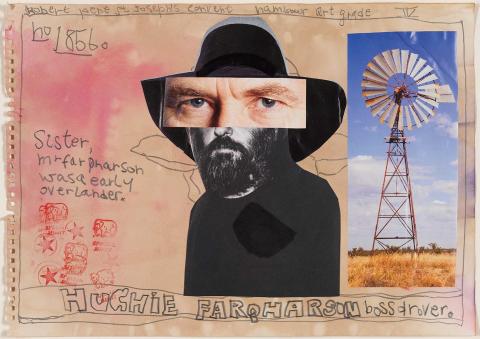

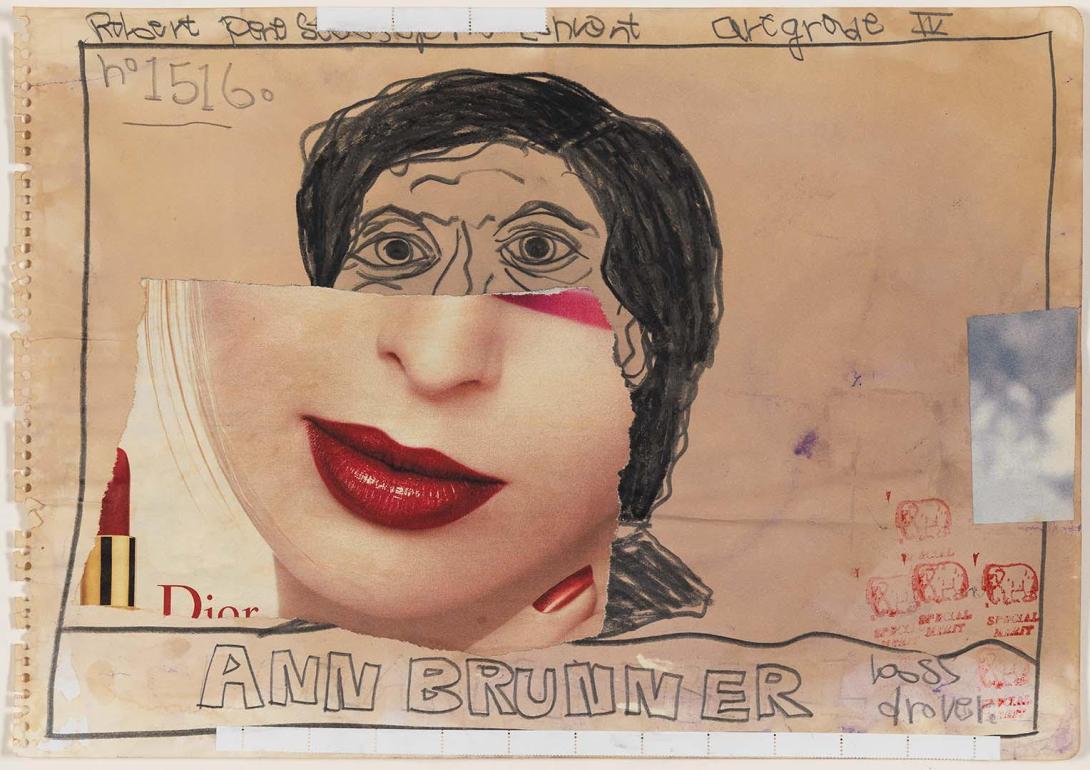

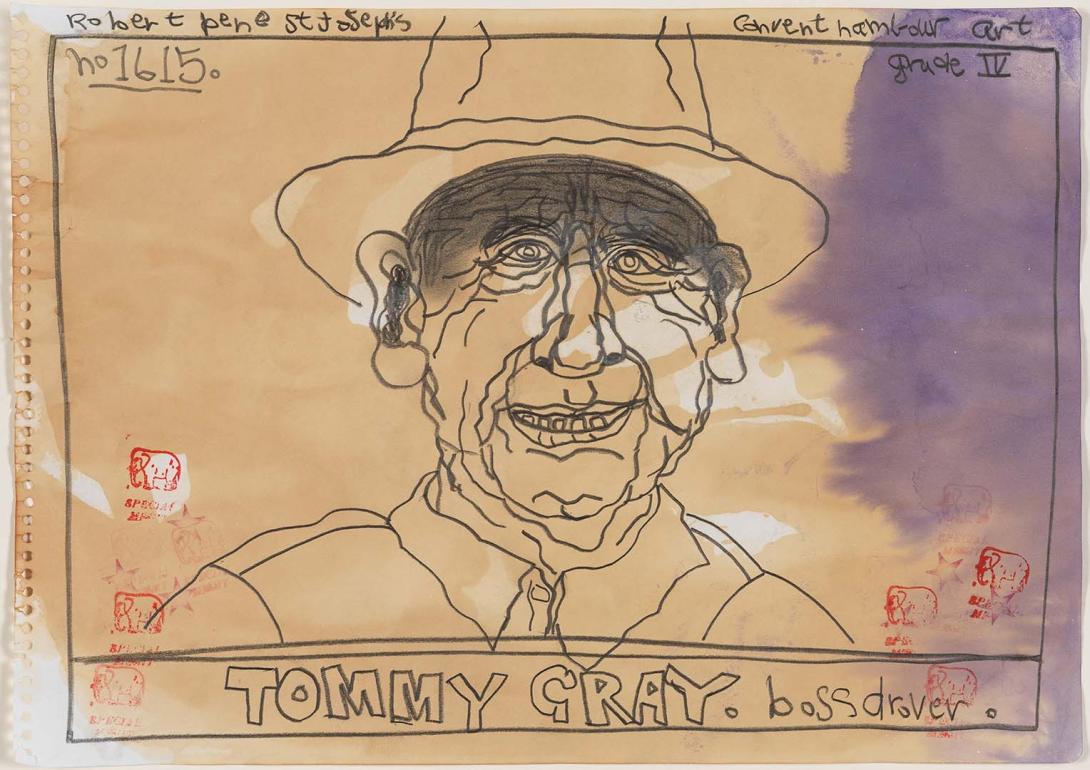

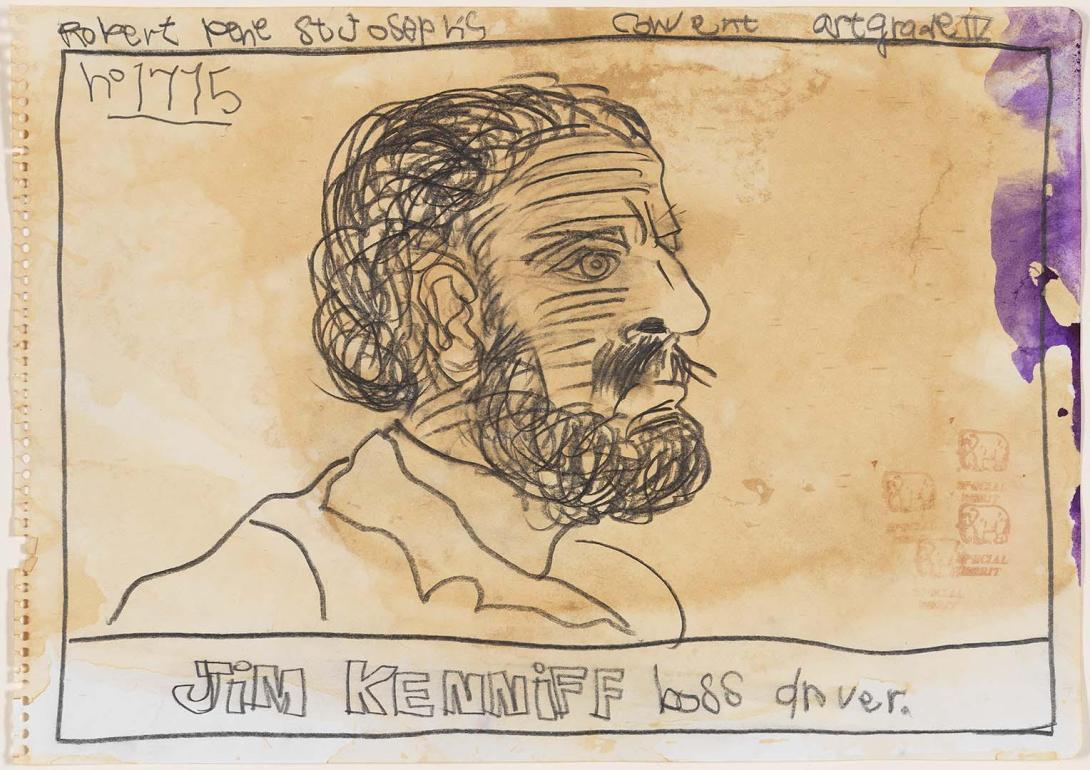

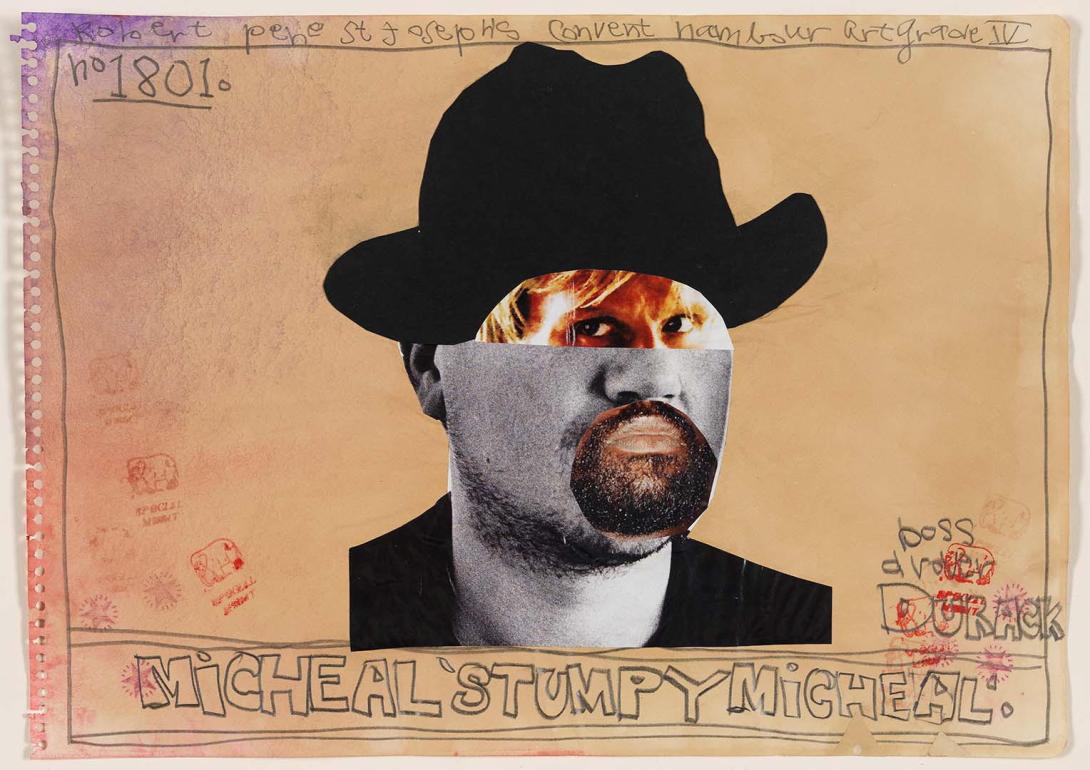

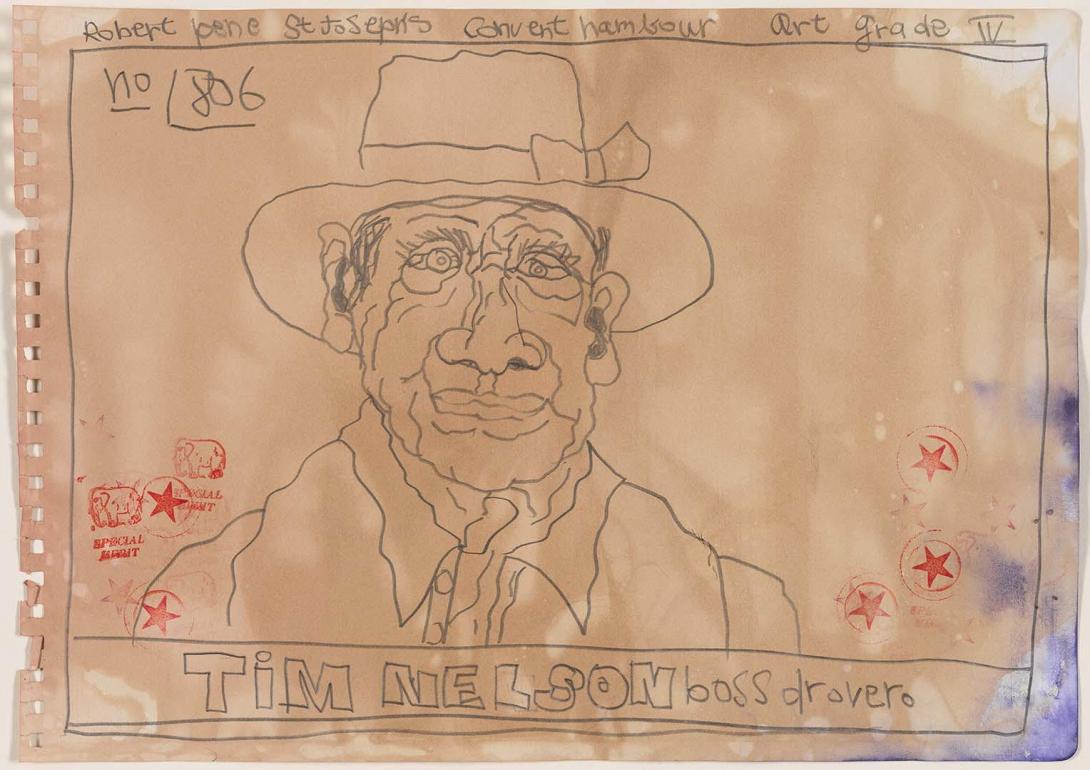

All images: Robert MacPherson / Australia QLD 1937–2021 / 1000 FROG POEMS: 1000 BOSS DROVERS ("YELLOW LEAF FALLING") FOR H.S. (detail) 1996–2014 / Graphite, ink and stain on paper / Purchased 2014 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation, Paul and Susan Taylor, and Donald and Christine McDonald / © Estate of Robert MacPherson / Photographs: QAGOMA

Anne Brunner (nee Edmonds) was born in 1925 in Ingham and, at 15, began her working life cutting timber. Interviewed in 2002 Brunner spoke about her education (to grade three) by correspondence school and going to work on Lyndhurst station during the labour shortages of World War II. While camped at the Clarke River, Brunner and her sister (Snow Edmonds, No. 564), along with their boss, George Towns (No. 476), rescued several American parachutists — survivors of a plane crash that the drovers had thought was the Japanese invasion. Brunner also remembered ‘driving nervous cattle past military police checkpoints around Townsville’, during the war, unable to stop while the cattle were moving and expecting to be shot by the sentries. Brunner later witnessed another military plane crash just eight kilometres from Darwin. Tragically, that time, there were no survivors. In the cattle camps Brunner said they had only the basics: ‘. . . a swag and a fly. A camp oven. About three or four billy cans . . . and you had to go a couple of mile to water’. They lived on corned beef and damper.1

- Ann Brunner, interview with Bruce Simpson and Bill Gammage, The Drovers Oral History Project, 2002.

Thomas (Tom) Gray (1905–41) was born at Onslow, Western Australia. His father, Richard Vickers, was a horse breaker and teamster, and his mother Ida was Aboriginal. Ida instilled in her children the importance of education and obtaining rights for Aboriginal people. Her family lobbied politicians for citizenship. Gray was a senior stockman at Anna Plains station in the mid 1930s where he was admired for his horse-breaking techniques. Remarkably for the time, Gray was so well regarded he was a dinner guest in the homes of white people from Port Headland to Derby. In 1935, Gray was engaged by police to pursue the killers of Daniel O’Brien, who had been murdered in the Great Sandy Desert. Gray acted as an intermediary between the police and Aboriginal people, as well as being the tracker, quartermaster and stock-handler. Gray was instrumental in the arrest of one of the murderers.1

In 1940, Gray enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and was assigned to the 216th Australian Infantry Battalion in Syria. He was killed in Lebanon and was buried in the Beirut war cemetery. His name is recorded at the Australian War Memorial.2

- Rod Moran, 'Gray, Thomas (Tom) (1905–1941)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1996, accessed online April 2015.

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Roll of Honour, Thomas Gray’, accessed April 2015.

James Kenniff (c.1869–1940) was convicted of stealing stock in northern NSW that he and his brother Patrick and their father James overlanded to Queensland. From Springsure they moved to the Upper Warrego where, with convicted cattleduffers Thomas Stapleton, John and Richard Riley and others, they launched a duffing ring, stealing cattle from Carnarvon and neighbouring stations. After another term in prison and their lease terminated, the Kenniffs moved across the Dividing Range to Lethbridge’s Pocket where they continued to threaten and terrorise.

Suspected of murdering two men (the manager of Carnarvon station and a police constable), the Kenniff brothers were arrested and tried in Brisbane. Although found guilty and sentenced to death, their executions were deferred. An appeal was financed by their supporters; the public saw the brothers as the last Queensland bushrangers. Patrick was executed on 12 January 1903 at Boggo Road and James had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment.1

- Grenfell Heap, 'Kenniff, James (1869–1940)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed online May 2015.

Patrick (Patsy) Durack (No. 925) became head of a large Irish family when his father Michael died suddenly.1 Striking it rich on the Victorian goldfields, Durack settled the family in Goulburn, NSW. In 1863 Durack, his brother Michael ‘Stumpy Michael’ (No. 1801) and brother-in-law John Costello (No. 663) made an unsuccessful attempt to run cattle in western Queensland, later establishing a property at Coopers Creek.

Setting off from Coopers Creek in 1883, the brothers overlanded 7000 head of cattle and 200 horses 4828km (3000 miles) to the Ord River in Western Australia. Beset by shortages of supplies and water, the deaths of three of their company and the loss of half the stock, the drove took two and a half years.2 Patsy went on to build a pastoral empire, his land holdings eventually including Ivanhoe, Argyle, Newry, Auvergne and Bullita, which were passed on to his four sons.3

- Kununurra Visitor Centre, The Durack Family, accessed July 2015.

- ‘Death of Mr. Michael Durack’, Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 1 September 1894, p.5, accessed July 2015.

- Kununurra Visitor Centre.

Tim Nelson is said to have been the second person to drive cattle into the north of the Northern Territory. Sometime around 1875 Nelson took 100 head of bullocks from Undoolya station in the McDonald Ranges to Darwin, using the Overland Telegraph Line as a guide.1 The bullocks had been ordered by a butcher in Port Darwin, presumably for slaughter, as had been the first mob herded into Darwin by D’Arcy Uhr (No. 1018) in 1872. Nat Buchanan (No. 2363) was the next to drive cattle through the Territory, about three years after Nelson’s trek. Buchanan’s charge was to deliver 1200 head of breeding cattle to Glencoe station, Port Darwin Camp, Margaret River, from Aramac station in Queensland.2 While D’Arcy Uhr and Nat Buchanan have much written about their lives and careers, after this trek Nelson seems to have fallen from record.

- ‘Men Who Made History for the Centenary: Drovers Who Pioneered, Fast Disappearing Band, Men Who Helped Make our History’, The Daily News, 9 October 1929, p.16.

- ‘Pioneer Drovers’, Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 28 January 1927, p.7.

John Finnis (1802–72) was born in Dover, England. In 1830 Finnis came to Australia, settling in Sydney. In 1831 he became involved in whaling, acquiring the barque Elizabeth. Finnis rode with Captain Charles Sturt (No. 719) in 1838, taking 300 head of cattle from New South Wales to south Adelaide where Finnis established a sale yard on West Terrace, Adelaide. He also established a cattle station at Mount Barker, bringing back several mobs from Sydney in 1839. Finnis was a partner in the first South Australian special survey and acquired 1250 acres at Mount Barker. His land dealings extended to New Zealand and in 1842 he returned to the sea, first as captain of the King Henry, then as the owner of the Joseph Albino.1

- HJ Finnis, 'Finnis, John (1802–1872)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online May 2015.

In 1890, the Farquharson brothers, Archie (No. 2101), Harry (No. 2298) and Hughie (No. 1856) took up the lease of Inverway, in the Northern Territory near the Western Australian border. The brothers spent the next three years working as drovers, also buying and selling stock until they had the money to begin their own herd. Harry was the stockman; Hughie kept the books and Archie was jack-of-all-trades.

The Farquharson brothers set the record in 1909 for the longest dry stage ever travelled by a mob on the Murranji Track, crossing 177 waterless kilometres (110 miles) with negligible stock losses. Starting with 1000 bullocks, they found both the Yellow and Murranji Waterholes dry. With cool overcast conditions, they droved the cattle around the clock, using hurricane lamps after sundown to lead them.1

- Bobbie Buchanan, In the Tracks of Old Bluey: The Life Story of Nat Buchanan, Boolarong Press, Salisbury, 2012, p. 116.

Daryl Horkings, an ex-horse breaker and drover from southern Queensland, was President of the Camooweal Drovers Camp Festival in 2012. The Drovers Camp commemorates droving tradition that helped to open up the north and aims to bring tourism and jobs to the area. Situated on the Queensland — Northern Territory border, Camooweal was where drovers camped by the Georgina River waiting to collect stock from the beef cattle stations of north-west Queensland, the Northern Territory and the Kimberley regions and ‘drove’ them south to southern railheads and markets.1

Horkings recalls: ‘I look back at those years I spent droving as the best years of my life. Freedom. Total freedom. I suppose you’re out on the road travelling like a bloody gypsy, no worries and no cares. Even when I describe those hard days they are still about freedom’.2

- President’s Report, The Drover’s Camp Camooweal, Cattle Pads, vol.9, no.3, November 2012, accessed May 2015.

- Evan McHugh, The Drovers, Stories behind the Heroes of our Stock Routes, Penguin Group, Australia, 2010, p.242.

Claude Kidman was born in Norton Summit, a town in the Adelaide Hills. He was the son of Charles Kidman, who was more interested in horse racing than the pastoral industries that involved his brothers. Claude started his ‘drovers’ education’ as a child, recalling that his uncle Sidney taught him the ropes when he was just nine. During his teenage years, Kidman was employed on a number of droving trips and in 1918 he joined the family company, Kidman Bros. Claude was a boss drover and was still droving when he was 68.1

- ‘Out Among the People, Queens Regatta,’ The Chronicle, Adelaide, 25 March 1954, p.55.

Pat Kennedy (c.1862–1930) is remembered in a short obituary from the Adelaide Observer. Kennedy was noted for his reputation as a good and trustworthy bushman and his work for Sir Sidney Kidman for over 40 years. Kennedy was responsible for moving the first of many mobs of cattle from the Cattle King’s Warenda station, in 1912, after it was sold.1

- ‘Veteran Cattle Drover Dies’, Observer, 9 October 1930, p.4, accessed July 2015.

James Alfred Laffin (1905–2002) was born in Camooweal, the youngest of seven children. The family left Camooweal in 1908 when Laffin’s father, Thomas Laffin, took a large mob (1200 head) to Cooladdi. When Laffin’s mother died, in 1921, Laffin was sent to Nudgee College, returning to assist his father at Elderslie station near Winton.

Laffin began working for Sir Sidney Kidman in 1927, droving between a number of stations including Rocklands, Alexandria, Soudan, Austral Downs, Tanbar, Gilpepee, Durham Downs, Glengyle, Palparra, Comongin, Davenport, Avon Downs and Maree in South Australia.

Laffin tried share-farming at Jandowie but the Depression forced him to return to droving. Laffin was manager of Bransby Out-station and Nockatunga, before becoming an assistant stock route inspector in 1954–55 in the Charleville area. He was employed by Queensland Railways, later moving to Deagon on his retirement.1

- Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame and Outback Heritage Centre, James Alfred LAFFIN, Camooweal, Qld, accessed July 2015.

Denis James (Jim) Ronan (1859–1932) came from Queensland. Ronan was renowned for the wide range of poetry he had memorised; he came from a generation of bushmen who carried classics in their pack saddles, reading by the light of the camp fires. Jim Ronan was the father of Tom Ronan (No. 141) who became a novelist. Jim Ronan took his son droving at the age of 14 and here Tom heard his father’s anecdotes, which he memorised and later used in his prize-winning books. Jim Ronan died during the evacuation of Darwin in the war years.1

- Mary Miller Durack, ‘A Writer is Born’, The Western Australian, 8 March 1952, p. 20.

Olaf (Michael) Sawtell (1883–1971) was born in Adelaide and educated at the Collegiate School of St Peters, but chose to become a ‘drover’s boy’ with Sir Sidney Kidman rather than continuing with his studies.

Sawtell worked at Annadale station on the Georgina River and along the Birdsville Track and in the Simpson Desert, recovering stray cattle. Working with Aboriginal boys his own age, Sawtell developed a lifelong respect for Aboriginal people’s spirituality. In 1904, Sawtell travelled to Western Australia where he worked at Oobagooma station, then travelled to the Northern Territory where he tried his hand at tin mining at Humpty Doo. Sawtell took a six-month ‘study holiday’ at Borroloola where he read Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1908 Sawtell took a lease at Trent Creek where he became converted to socialism after reading Merrie England (1895). Sawtell opposed detribalisation of Aboriginal people, deeming it as destructive to their belief system. In later life Sawtell was a prolific contributor to the press and participated in an Australian Broadcasting Commission forum opposing British weapons testing in Australia.1

- Jill Roe, 'Sawtell, Olaf (Michael) (1883–1971)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed online April 2015.

Charlotte McKenzie’s journey in 1948 was reported by the Adelaide Advertiser when, with her husband and one Aboriginal assistant, she overlanded 1250 cattle over the Murranji Track, the route pioneered by Nat ‘Bluey’ Buchanan (No. 2363) and Sam Croker (No. 982) in 1886.1

- 'Long Trek For Woman Drover', Advertiser (Adelaide), November 26, 1948, p. 8, viewed 2 July, 2015.

Margaret May Cole (nee Bridge) (1885–1964) was raised on the road, where she had a practical education. By the time she was ten Cole had learnt how to ‘handle horses, cattle and dogs’, she could drive a covered wagon and use a gun. Cole took on roles that were equal to those of older, experienced, male drovers, doing the same work as stockmen during her family's move from Normanton to the Kimberley and, in the absence of her father, protecting her mother and siblings from the threat of attack by Aboriginal people. The family moved to the station that would be called Mabel Downs by her proud father (Joe (Joseph) Bridge, No. 1832). She married Tom Cole (No. 2308), also a renowned drover and cattle pioneer. Cole retired to ‘travel constantly throughout Australia visiting her relatives’ and was buried in a small cemetery near Alice Springs, ‘close by the grave of Albert Namatjira’.1

- ‘Margaret May (`Mabel') COLE (nee Bridge), b. 23rd May 1885, Normanton QLD, d. 1st November 1964, Alice Springs NT’, Australian Stockman's Hall of Fame and Outback Heritage Centre, accessed May 2015.

James Patrick Church (1927–96) was born in Townsville. He started working on stations at 14, first at John Brabon’s property Glenrowan on the Black River, then at Granite Vale on the Ross River, where his duties included horse breaking, roughriding and general station work. Church droved with Charlie Furber (No. 419) and Billy Lane (No. 2140). In 1953, Church worked at the Orient for the Tropical Cattle Company, later moving to Atherfield station working for Messrs Kelly and Hardy. Church purchased his own station Strathelen in 1959, also putting together a packhorse plant of 40 horses. He droved for a number of stations: Donors Hill, Fort Constantine, Augustus Downs and the Stanbroke Pastoral Company. In 1967, he ended his droving career, buying a cattle transport and running it in conjunction with Strathelen station.1

- ‘James Patrick CHURCH, b. 26th April 1927, Townsville QLD, d. 19th December 1996, Charters Towers QLD’, Australian Stockman's Hall of Fame and Outback Heritage Centre, accessed May 2015.

‘Mulga Jim’ McDonald is believed to have died on the Murranji Track, according to the account of Frank Lacy. 'Mulga Jim' was the boss drover on a trip to Wave Hill when, having been sick with malaria for most of the way, he lay down under a tree and succumbed to the illness. Explorer Michael Terry, driving his car across the Murranji in 1923, states he saw Mulga Jim’s grave near the Murranji Waterhole; however, the inscription on the grave — ‘A McDonald, died 3 May 1921’ — does not match the dates Lacy provides in his account.1 Another account by Norm Whatley (2111), who worked on Mornington station in the Kimberley, recalls that Jack ‘Smiler’ Smith (1063) told him about a droving trip across the Murranji in the 1920s, where the boss drover and another man died on the track.2 In another unconfirmed story, Alice Yarwar, mother of Aboriginal artist Amy Laurie, ‘was given to Mulga Jim, an Aranda man, by Jim McDonald the owner of Kirkimbie station in the Northern Territory',3 making Amy ‘Mulga Jim’s’ granddaughter.

- Darrell Lewis, The Murranji Track: Ghost Road of the Drovers (2nd ed.), Boolarong Press, Brisbane, 2011, p.35.

- Lewis, p. 31.

- Austlit, Amy Laurie, accessed July 2015.

James Stirling was a pioneer of the Snowy Mountains region. His father had been the first man to ‘select’ land in the Orbost district in east Gippsland The area where Stirling and his brother John grew up was known as the Old Station. When the family first arrived the nearest settlements, Orbost station and the settlement at Genoa, were many miles away. Although distant from large communities, the Stirlings had family nearby. An uncle, Mr TT Stirling (of Nowa Nowa), owned a cattle run which stretched from Lake Tyers to the Bemm River, a distance of some 46 miles (75km).

Later in life, Stirling became the proprietor of the Marlo Hotel and was also involved in the mining industry at Walhalla. After a long drive through a very cold wind Stirling suffered severe exposure. Within weeks he succumbed to Erysipelas or St Anthony’s Fire and died at the age of 63.1

- ‘Death of Mr. James Stirling’, Snowy River Mail, 15 June 1917, p.3.

In 1890, the Farquharson brothers, Archie (No. 2101), Harry (No. 2298) and Hughie (No. 1856) took up the lease of Inverway, in the Northern Territory near the Western Australian border. The brothers spent the next three years working as drovers, also buying and selling stock until they had the money to begin their own herd. Of the brothers, Archie was jack-of-all-trades.

The Farquharson brothers set the record in 1909 for the longest dry stage ever travelled by a mob on the Murranji Track, crossing 177 waterless kilometres (110 miles) with negligible stock losses. Starting with 1000 bullocks, they found both the Yellow and Murranji Waterholes dry. With cool overcast conditions, they droved the cattle around the clock, using hurricane lamps after sundown to lead them.1

- Bobbie Buchanan, In the Tracks of Old Bluey: The Life Story of Nat Buchanan, Boolarong Press, Salisbury, 2012, p. 116.

Patrick Cahill (c.1863–1923) was born in Laidley. With his brothers Tom (No. 2040) and Matt (No. 1385) Cahill accompanied Nat Buchanan (No. 2363)m overlanding 20 000 cattle to Wave Hill station, NT.1 Cahill became manager of Delamere station, then trekked north to the Alligator River where he was a buffalo hunter.2

Cahill and his partner employed Aboriginal workers to produce buffalo hides and horns during the dry seasons. Learning Aboriginal language and customs, he gained respect as a trusted ‘medicine man’.3 Cahill’s good relationship with the Aboriginal people resulted in his appointment as protector and manager of the reserve in Oenpelli (Arnhem Land).

Cahill was one of the most popular men in the Northern Territory. Visiting Darwin in 1898, AB Paterson light-heartedly listed the main conversational pieces of Darwin as the ‘cycloon’ (of 1897), the GR (the government resident) and Paddy Cahill. Cahill is buried in Randwick Cemetery.

- MA Clinch, 'Cahill, Patrick (Paddy) (1863–1923)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1979, accessed online April 2015.

- JA Gilruth, ‘Paddy Cahill Bushman, Hunter, Sailor’, The Argus, 10 February 1923, p.4.

- Gilruth, The Argus, p.4

Alfred Giles, uncertain of his exact birth date, recalled going to South Australia as a boy in 1849. He reckoned on being ‘more than 80’ in 1926. Alfred grew up on the Wakefield River with three brothers and two sisters. Alfred found adventure and opportunity building the overland telegraph.

With his brother Arthur (No. 1673), Alfred opened up pastoral properties including Newcastle Waters and established Springvale and Delamere stations. The Giles brothers drove 2000 cattle and 10 000 sheep to stock these stations, travelling up to 2200 miles (3500km) over ‘unoccupied’ country.

Arthur Giles invested in the mining industry in both the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Described as ‘clever, energetic, persevering and enterprising and a fair artist with water colours’, Arthur is said to have been attended by ill luck on most of his ventures, dying a poor man, after living a hard and chequered existence.1

- ‘Alfred Giles, Enjoying Life at 80, Bush Still Calls’, The Mail (Adelaide), 22 September 1928, p.3.

Harry (No. 2223) and Ruby Zigenbine were the parents of eight children who all grew up working stock across Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Harry Zigenbine was brought up in Charters Towers on a station where his father was the manager and worked under the Kidman boss drovers. A true bushie, Zigenbine’s philosophy was mirrored in the rearing of his children; he recalls, ‘in my day . . . a cattle man was flogged until he had learnt not to make mistakes. I was broken in rough and I’ve broken my kids in the same way’.1

- Douglas Lockwood, ‘A Blue-eyed Brunette Bosses the Overlanders’, The Courier-Mail, 13 May 1950, p.2.

Reginald Raymond Tighe (1931–) was born at Julia Creek, the son of a drover working in the Hughenden, Prairie, Stamford and Tangoran areas of Queensland. In 1949 Tighe went droving with his father who had been contracted by the owners of Cambridge Downs. In 1950 Tighe went to the Northern Territory where he drove 1350 bullocks from Wave Hill to Dajarra in Queensland.

The drover’s strike of 1951 prompted him to change employers and Tighe went droving for the owners of Coolibah station. On a drive taking 1500 head of mixed cattle from Coolibah to Delmore Downs Tighe was deserted by his stockmen, leaving him and just one other stockman to complete the trip. To raise help, Tighe left a note on top of a saddle which was placed on an ant bed in the middle of the track for his father John coming along the track later. In 1954 Tighe mustered his horses off the Common at Camooweal and left for Argyle station, owned by the Durack family. Tighe did a number of trips from Argyle into Wyndham, finally selling his droving plant to Rod Quilty and Sam Lilley (No. 102).1

- ‘Reginald Raymond TIGHE, b. 19th November 1931, Julia Creek, Qld’, Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame and Outback Heritage Centre, accessed April 2015.

John ‘Boomerang’ Brady (c.1865–1926) was born in Toowoomba. His first droving trip was to the Johnstone River in north Queensland. Brady got his nickname ‘Boomerang’ while working at Fort Constantine station (north-west Queensland) after a horse fell on him, severely breaking his leg. He spent four months in Cloncurry Hospital, but his leg was so badly set it remained bent like a boomerang.1 When Brady was discharged from hospital, he headed towards the Georgina River to Idamere (now Glenormiston) station, where he was employed to take a mob to Tinnenburra station in south-west Queensland.

Brady died about 104km (65 miles) out from Newcastle Waters and he was buried there in his swag.2 Four saplings marked the grave and his sister subsequently placed a headstone there.3

- ‘Out Among the People’, The Advertiser, 27 January 1954, p.4.

- Bill Bowyang, ‘On the Track’, Townsville Daily Bulletin, 19 December 1941, p.7.

- FA Steinfort, ‘A Lonely Grave. The Last of Boomerang Brady’, Northern Standard, 17 January 1928, p.3.

Walter Rose delivered 2050 cattle from Lissadell station, near Lake Argyle in Western Australia to Richmond in Queensland. Rose was ‘a native of Armidale (NSW), a bushman to the manner born and of great experience’. He began the journey in 1905 with 3750 cattle divided into three mobs; drovers John Martyr (No. 2324) and E Brodie (Jack Brodie, No. 602) led the first two mobs, followed by Rose with the third mob. The mobs crossed the Northern Territory from west to east, circumventing a cattle-flooded market in Perth. However, they took a great risk as the Territory was ‘suffering from an unusual drought’ and diversions to find water and grass to keep the stock alive made the trip even longer — 22 months on the road. Undeterred by the hardships of this first journey, including the loss of three men and significant numbers of cattle, the Observer noted 'Mr Rose has been engaged for another trip to Lissadell . . . leaving Charleville about Christmas time for the purpose of crossing the big rivers before the wet season sets in'.1

- 'Droving in Northern Australia’, Observer (Adelaide), 1 December 1906, p. 28, viewed January 2015.

In 1890 the Farquharson brothers, Archie (No. 2101), Harry (No. 2298) and Hughie (No. 1856) took up the lease of Inverway, in the Northern Territory near the Western Australian border. The brothers spent the next three years working as drovers, also buying and selling stock until they had the money to begin their own herd. Of the brothers, Harry was the stockman.

The Farquharson brothers set the record in 1909 for the longest dry stage ever travelled by a mob on the Murranji Track, crossing 177 waterless kilometres (110 miles) with negligible stock losses. Starting with 1000 bullocks, they found both the Yellow and Murranji Waterholes dry. With cool overcast conditions, they droved the cattle around the clock, using hurricane lamps after sundown to lead them.1

- Bobbie Buchanan, In the Tracks of Old Bluey: The Life Story of Nat Buchanan, Boolarong Press, Salisbury, 2012, p. 116.

Edna Jessop (nee Zigenbine) was born in Thargomindah, south-west Queensland, in 1926 and was raised in droving camps with her three sisters and four brothers. Jessop became Australia’s first female boss drover at 23 when, along with her sister Kath (No. 235), her brother Andy (No. 152) and four ringers, she took 1550 bullocks the 2240km across the Barkly Tableland to Dajarra, near Mount Isa in Queensland. Jessop’s achievement earned her almost a full page in the Courier-Mail and she was swamped with letters from as far away as Norway with proposals of marriage and from others wanting to join her droving team.1 She married John Jessop (No. 536). ‘Give my Regards to Edna’, a song written by Stan Coster and recorded by Slim Dusty, was played at her funeral.2

- Douglas Lockwood, ‘A blue-eyed Brunette Bosses the Overlanders’, The Courier-Mail, May 13, 1950, p.2.

- Kevin Meade, ‘Drovers doff hats to their Dame, 80.’ The Australian, September 22, 2007, accessed December 2014.

Donald MacDonald came to Sydney from the Isle of Skye. He married Anne (nee McAllum), from Mull, in 1849 and they had three sons, Dan (Donald), Charles (Charlie, No. 1277) and William Neil (Bill, No. 770), who were raised at Laggan in New South Wales.

MacDonald was killed shortly prior to his sons’ epic cattle drove to the Kimberley, but his vision and legacy ensured the establishment and success of one of Australia’s largest cattle stations, Fossil Downs.1

- Government of Western Australia, Heritage Council, State Heritage Office, Fossil Downs Homestead Group, accessed July 2015.

Clarence Pankhurst (1921–2000) was born in Renmark, South Australia. At 12, Pankhurst went to work on a wheat farm. After just a few months he went fruit picking, then bought an old Chevrolet Superior with his brother Frank, planning to go to Queensland. Pankhurst then ‘decided to head for the wide open spaces out in the Northern Territory, go out and get into the cattle industry . . .’

In Camooweal, Pankhurst was given a droving job by boss drover Sid Howard (No. 2155). Pankhurst recalls, 'One trip from Creswell Downs to Bourke we were on the road for more than two years being paid my regular ringer's wage of two pounds, eight shillings a week where you were expected to shoe, ride a buck jumper, horse tail, cook — you name it do the lot.'

Pankhurst gained the respect of owners and stock inspectors and, at 21, became a boss drover when he was offered a job on a property owned by the British pastoral company Vestey. Pankhurst is credited with a small part in The Overlanders, a film made in 1946 featuring Chips Rafferty.1

- Anne Marie Ingham, The Boss Drover and his Mates, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2011, pp. 9–57.

Frank Hann (1846–1921) arrived in Victoria at the age of five. In 1862, he went to Queensland where his first job was taking a mob of 2000 head of cattle to the Condamine. Hann acquired Bluff Down, Maryvale and Lolworth stations and, later, Lawn Hill station. Hann became the first white man to take stock from the Gulf into the Northern Territory. Hann was commissioned by the Western Australian Government to open up stock routes and pastoral areas; he crossed the 1900 miles (3120km) from the Indian Ocean to Oodnadatta three times.1

- ‘Death of Mr. Frank Hann’, the Australasian (Melbourne), 27 August 1921, p.34.

Nat Buchanan (1826–1902) arrived in Sydney in 1837 with his parents, Lieutenant Charles Henry and Annie Buchanan, and his four brothers.1, 2 Buchanan took up droving after he returned from the Californian gold rush. In 1863, he married Katherine Gordon of Ban Ban station, Maryborough, and they lived at Bowen Downs station where he was first manager and then partner of the Landsborough River Co.

In 1878, Buchanan led the Glencoe station stock drove, taking 1200 head of cattle from Aramac station in Queensland to the Adelaide River, opening up the territory to the advancement of white settlers. In 1883, Buchanan took the first cattle into the Kimberley, crossing Victoria River country with 4000 head of stock for the Ord River station.

Buchanan, with his son and Sam Croker (No. 982), pioneered the Murranji Track, crossing the top of the Northern Territory from Newcastle Waters to the Victoria River.

- ‘Pioneer Drovers’, Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 28 January 1927.

- Sally O’Neill, Buchanan, Nathaniel (Nat). Australian Dictionary of Biography, viewed June 2015.

In 1904, ‘Brigalow Bill’ Ward was the first white settler on the Humbert and a notorious cattleduffer (cattle thief).1 In 1908, Ward wrote to authorities seeking to have his annual land permit converted to a long-term lease.2 Unbeknownst to him, his block had already been chosen as an Aboriginal reserve.3

When police went to investigate Ward’s complaints about local Aboriginal people, they found he was apparently duffing from Victoria River Downs. Ward’s problems continued when two 'ruffians’ — who were spending Christmas with him — abducted Judy, a local Ngarinman/Ngaliwurru woman. They rode off to Borroloola, pursued by Ward across the Murranji Track and the Barkly Tableland. Judy was retrieved by Ward and returned to Humbert River.

Ward’s Humbert River block was declared an Aboriginal reserve in June 1909, but Ward refused to leave, squatting there for some months. Later, Judy stole his gun, allowing a group of men to spear him to death when he bathed in a creek near the homestead.4

- Charlie Schultz, and Darrell Lewis, Beyond the Big Run, University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, Qld, 1995, p.229.

- Deborah Bird Rose and Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Hidden Histories: Black Stories from Victoria River Downs, Humbert River and Wave Hill Stations, Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, 1991, p.120.

- Darrell Lewis, A Wild History: Life and Death on the Victoria River Frontier, Clayton, Vic., Monash University Publishing, 2012, p.273.

- Lewis, p. 276.

Thomas Gerald Clancy (1835–1914) is thought to be the Clancy brother who inspired AB Paterson’s ‘Clancy of the Overflow’. Born in Ireland, Clancy migrated to Melbourne with his family in 1841. He went to a Catholic school in Lonsdale Street before becoming a ‘runner’ for a newspaper, the Patriot, followed by a job as a shepherd with Barnes, Morton and Co. Clancy was in the crowd that farewelled Burke and Wills when they left on their expedition to the interior, and he was at Bendigo when gold was discovered in 1851.

Droving all through the central west, Clancy saw many parts of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. In his poem, Paterson idealises the freedom of the droving life. In 1897, Clancy penned a poem to Paterson in response and Paterson’s signature may still be seen as witness to Clancy’s will.1

- ‘Clancy’, Daily Mercury, 5 January 1944, p.3.

Edward Spencer Kennedy (1878–1936) was born in Goulburn, NSW. Kennedy was a horse trainer and became one of the best horse breakers on the north coast of New South Wales. He also trained Te-Kuti, a champion pony high jumper belonging to Mr Fred Baker. Kennedy had been involved in coach driving, droving and then hauling cream on the Main Arm near Burringbar, before becoming employed on the ‘tick staff’ (the government tick eradication program).1 Cattle ticks were introduced into Darwin in 1872 and, with no effective treatment, spread across Queensland and down to NSW.2

- ‘Obituary, Edward S. Kennedy’, Northern Star, 11 August 1936, p.8, accessed July 2015.

- NSW Department of Primary Industries, Tick fever, accessed July 2015.

Harry Redford (or Readford) — aka ‘Captain Starlight’ — got his reputation as a drover in 1870, after stealing 1000 cattle from Bowen Downs station, near Longreach, and driving them 1500 miles (2414km). Redford’s route took him down the Thomson, Barcoo, Cooper and Strzelecki rivers, thus pioneering the Strzelecki Track.

Redford was finally brought to trial for the Bowen Downs affair in 1873. He had been on the run, then captured and held in prison for a year. A jury returned a verdict of not guilty, even though the case against Redford was understood to be clear-cut, and outrage at the verdict echoed all around Australia.1

The law finally caught up with Redford for horse-stealing and he served an 18-month jail sentence. Following his release, Redford continued droving cattle in Queensland and the Northern Territory. He apparently pioneered his own property, Corella Downs, now part of Brunette Downs. Redford’s story and other tales of Australian bushrangers were woven together by Rolf Boldrewood to create the iconic ‘Captain Starlight’ character in the novel Robbery under Arms.

- Roma District Court, ‘Roma District Court’, the Brisbane Courier, 18 February 1873, p.3.