Namatjira and the Hermannsburg School

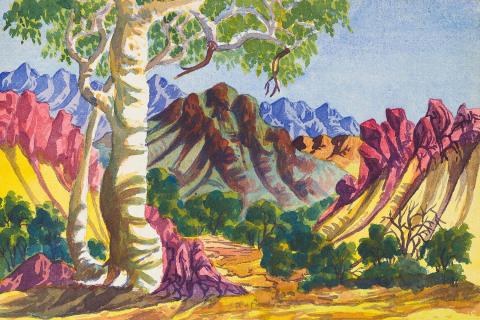

Albert Namatjira painted not so much the things he saw, but what he felt inside.

One man’s vision

Albert Namatjira is a giant of Aboriginal art; his name is renowned and his legacy far-reaching. There are few Aboriginal artists today who do not know of Namatjira and have not been inspired by his style and story. At one time he was among the most recognisable celebrities in the country — no mean feat for any artist, let alone an Arrernte man from a tiny community in the centre of Australia. His personal vision initiated a school of painting, which developed into a movement, and has now become a tradition.

Namatjira was born in 1902 at Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission into the Western Arrernte people; he was named Elea. In 1905, his parents Namatjira and Ljukuta were baptised Jonathan and Emelie, and their young son was given only a Christian name — Albert.

Working as a blacksmith, carpenter and stockman, as a young man Albert became known as something of an entrepreneur, making artefacts (often scenes with burned incisions or traditional markings) and selling them to tourists and military personnel who were stationed nearby. He also spent large amounts of time travelling through his country and further afield as a ‘camel boy’, transporting goods by camel-train.

During the 1930s, many artists visited Ntaria (Hermannsburg), hoping to be inspired by the ‘real’ Australia. In 1934, Albert viewed an exhibition there by visiting watercolour painters Rex Battarbee and John Gardiner, and made a conscious decision to pursue a career as an artist. His intention was clear: if these men could make a living from painting his country, then surely he could too. He soon began painting landscapes and studies of people and animals without any instruction, but he quickly became frustrated at his own inexperience and wished to learn more. Through the Mission, he requested that when Battarbee returned he offer his services as camel boy and guide. In 1936, the Victorian artist returned, and was escorted by Albert on a two-month painting expedition through Arrernte country. In return, Albert observed Battarbee and received some training. This was to be the only formal tuition of his career.

Albert’s technical ability developed markedly and, though his skill and insight in painting Arrernte landscapes was admired by many, his work was still not seriously considered by the usual art institutions. As he gained attention, he adopted his father’s name, Namatjira, as a surname to fit in with the expectations of European society. He soon rose to remarkable fame, eventually being presented to Queen Elizabeth II in 1954, while his portrait painted by William Dargie won the 1956 Archibald Prize in Sydney. He was presented as the poster boy for assimilation — an Aboriginal who could paint like the white man and dine at his table — and was consequently the first Aboriginal person granted citizenship of Australia in 1957.

What has since been realised is that Albert used the European watercolour landscape as a means of making money while still maintaining links to culture and country. It is important to note that he held his responsibilities to his family above all else — he was said to be happiest in the company of his family on painting trips to country.

The Hermannsburg School: a movement

Following in Albert Namatjira’s footsteps, other members of his family and community were encouraged to take up painting. The first to join was Walter Ebatarinja, whose superior ties to the Hermannsburg area meant that Albert, whose country was further west, was obliged to teach him first. Others followed, including Walter’s wife Cordula; Otto, Edwin and Reuben Pareroultja; Richard Moketarinja; Henoch and Herbert Raberaba; Benjamin Landara; and the ‘sons of Namatjira’ — Enos, Oscar, Ewald, Keith and Maurice, and Albert’s eldest grandson, Gabriel. Rex Battarbee returned to Central Australia often, and became a mentor and advisor to the group.

The most successful artists were often from one of the family painting groups — Ebatarinja, Namatjira, Pareroultja or Raberaba. The presence of family meant a certain safety and stability for the artists, and a more intimate group in which to test new ideas. Each of the families developed unique styles to which the artists added their own idiosyncratic touches.

Albert, as senior man, would explain the stories implicit in the landscape, and painting expeditions resembled ceremonies in times past, where important information about country had been revealed. (These ceremonies had been suppressed since the establishment of the Christian missions.) Albert’s knowledge of place was revealed on the few occasions he was asked about the significance of his work. In Roland Robinson’s book The Feathered Serpent, for instance, under the name of ‘Tonanga’, he told of three special creation narratives relating to Arrernte country, while he also spoke of his family’s connection to these places in the film Namatjira the Painter:

It is my father’s country. It is my country, too. He was a flying ant. He came flying all the way down from the MacDonnell Ranges, way over from Mount Sonder, way down the Finke River, way down the Ormiston. The old men they tell us these things and I tell my sons. They, too, must know about my father’s country.1

One member of this group who deserves singular mention is Otto Pareroultja. Encouraged by his younger brother Edwin’s success, Otto began painting in a style that was immediately seen as a primitive and totemic departure from an otherwise staid genre. His colourful, striated trees and monoliths drew comparisons with decorated people and accoutrements in Arrernte ceremony.

In his earlier works, trees seem to move through the landscape, taking the shape of Arrernte ancestor spirits, while masses move and morph and forms and faces appear in cliffs and rocks. Later, Otto’s oeuvre focused on a repeated rock mass — believed to be the hill associated with his Native Cat Dreaming, near Mount Sonder — often framed by two trees painted as if ceremonially decorated or scarred. This can be seen as a form of self-portraiture, with the scarred trees representing Pareroultja’s body as he passed through ceremony, with the authority he gained being imbued and strengthened in his repeated depictions of this place.

A living tradition

After the rise in popularity of their work through the 1950s and 1960s, most of the artists of the Hermannsburg School moved from Hermannsburg to Alice Springs in search of a better life. Unfortunately, prejudice prevailed, and access to housing and basic services was limited, with many people forced to live in shanty camps on the outskirts of town. Today, while their descendants live in the same ‘town camps’, family and tradition have remained strong here, allowing the movement to survive.

Since the 1970s, this style of watercolour landscape has been overshadowed by Western Desert ‘dot’ paintings. The two styles are often seen as competing, but for Aboriginal people the distinction between the symbolic and the pictorial is blurred. The primary focus — the country and all it embodies — is represented in both forms of art. As the important artist and activist the late W Rubuntja Pengarte, OAM, stated:

All we’re doing now is still Dreaming, it’s still there. Doesn’t matter what sort of painting we do in this country, it still belongs to the people, all the people, and we’ve got to keep it going.2

At Hermannsburg, the tradition is being kept alive in a different way. When the Arrernte community assumed responsibility for the community in 1982, they sought avenues to develop and promote the welfare of residents. Many had experience modelling clay figures through their schooling, and a request for instruction in ceramics was lodged, resulting in the appointment of a ceramics teacher and the establishment of a pottery studio. After nearly two decades of operation, a core group of dedicated women artists has developed a unique style, combining Native American–style coil-built pots and clay figures with Arrernte landscapes.

The Hermannsburg Potters have retained strong links to the watercolour landscape painting movement that many remember from their childhood. It continues as a source of pride in the community, as artist Judith Inkamala explains:

We like to watch them old pictures. Copy them a bit. Still keep it, remembering. All our young people should learn the watercolour. We saw Albert and the others. We know it and carry it in our work. We the same family.3

The original vision of Albert Namatjira grew into something great. The Hermannsburg movement’s legacy has inspired from Ginger Riley Muduwalawala to Tracey Moffatt and Billy Benn Perrurle. Namatjira’s influence lives on now and into the future.

Bruce McLean is former Curator, Indigenous Australian Art at QAGOMA.

Endnotes

1. Albert Namatjira, quoted in Namatjira the Painter, documentary film, Lee Robinson (director), Charles Mountford (associate producer), Axel Poignant (cameraman), Commonwealth Department of Information, 1947.

2. Jane Hardy, JVS Megaw and Ruth Megaw, The Heritage of Namatjira, William Heinemann Australia, Port Melbourne, Vic., 1992, p.289.

3. Judith Inkamala, interview with the author at Hermannsburg, 24 July 2008.

Explore works from the Hermannsburg School

Digital Story Introduction

THE HERMANNSBURG SCHOOLOswald A Wallent Collection of Hermannsburg Material

Read

ESSAY: Namatjira's Albert and Vincent 2014

Read storyDigital story context and navigation

THE HERMANNSBURG SCHOOLExplore the story

Digital Story Introduction

THE HERMANNSBURG SCHOOLQAGOMA COLLECTION: Hermannsburg Potters

Read digital story

Digital Story Introduction

THE HERMANNSBURG SCHOOLQAGOMA COLLECTION: Hermannsburg painters

Read digital story

Digital Story Introduction

THE HERMANNSBURG SCHOOLOswald A Wallent Collection of Hermannsburg Material

Read

‘Namatjira to Now’

Oct 2008 - Feb 2009

About this page

Related resources