(Re)framing fashion

When QAGOMA acquires an artwork for its Collection, it may or may not include its original frame. Part of Robert Zilli and Damian Buckley’s job, as conservation framers, is to ensure each work has an appropriate ‘home’. But artwork frames are just as subject to the whims of fashion — and even politics — as any other design object.

George Romney's Mrs Yates . . . 1771, installed at QAG following restoration, alongside work by Angelica Kaufmann (left; housed in a patinated, gilded frame) and Peter Paul Reubens (right; in an Italian baroque–style frame made in twentieth-century England), April 2024 / Photograph: J Ruckli, QAGOMA

ROBERT ZILLI: Frames are inherently objects that can be removed from paintings. It’s very easy for someone to say, ‘That doesn’t fit my décor. That doesn’t fit my style. It’s too gold. It’s not gold enough. We’ll put something else on it.’ It’s very, very common.

DAMIAN BUCKLEY: Napoleon, for instance, reframed a lot of his collection in a style we now call Empire. It was a move away from the carved luxury frames that were produced for the monarchies, which were considered too ostentatious to fit in with his political manifesto.

RZ: There was once a worldwide fashion of standardising frames for gallery collections. A lot of original frames were removed and ‘gallery frames’ were put on entire collections. This also occurred at QAG, well before my time. Fortunately for us, a lot of the original frames that were removed from their paintings were kept and are in our frame storage room. We are methodically working through these and reuniting them with their paintings. A great example of this is two works in our Collection by Godfrey Rivers. Sometime prior to the Collection moving to QAG in 1982, these two artworks were reframed — the original frames were stored off site and forgotten. My understanding is that, sometime in the late 1980s, QAG was contacted by another government department to say, ‘We’ve found these two frames and they have labels on the back: does “Godfrey Rivers” mean anything to you?’. And so they were reunited with the paintings.

Robert Zilli and Damian Buckley inspect the Romney frame’s carved details before beginning restoration, QAG Framing Studio, August 2022 / Photograph: Natasha Harth, QAGOMA

DB: The way the Dutch changed framing [during the seventeenth century] is so interesting, in terms of the use of ebony. They were still moving away from the use of gold or elaborate ornament — it was a more subdued style, but the ebony timbers they used to make the frames were extremely expensive. It just wasn’t shouting it wealth so much. [The look became so popular, in fact, that due to the cost and rarity of this dark hardwood, many frames were ‘ebonised’ — stained or painted black. See (Dutch canal scene) below.]

RZ: From the beginning of the nineteenth-century, people were looking at faster and more efficient ways of manufacturing — making things cheaper for the general population. What we call ‘applied ornament’ has been around since the renaissance — it’s not a new idea to cast material in a mould and adhere it to a piece of furniture or a frame — but it really took off in the nineteenth century. A compo (moulded composition) frame will always have a timber profile, and then the moulded compo is glued to that. That’s why we call it applied ornament — it’s applied when softened, and once it’s hardened up you can gild or paint it. Even commercial frames today are made in the same way.

An ebonised frame in the QAGOMA Collection, housing Ian Fairweather’s (Dutch canal scene) 1918 / Oil on cardboard / Purchased 1983 / Collection: QAGOMA / © Ian Fairweather/DACS/Copyright Agency

Explore related frames at QAGOMA

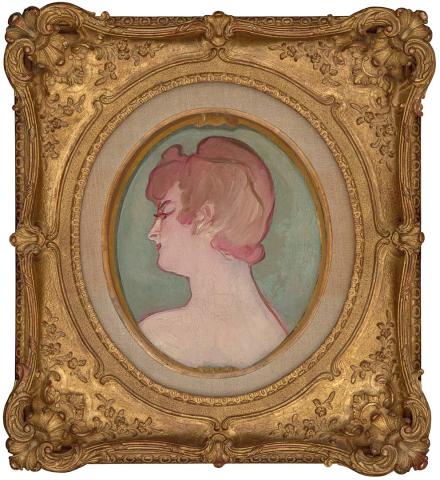

The frame for Mrs Yates as the Tragic Muse, Melpomene 1771 is a pine frame made in the rococo style, right as tastes were turning towards neoclassical restraint. Explore frames from across the QAGOMA Collection that typify framing fashions through the ages: the rococo opulence of the frame for Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Head of a girl 1892; the bronze-painted ‘gold-look’ of the frame for Patrick Nasmyth’s Cottage at Clapham early 19th century; and the grand neoclassical frame of Godfrey R Rivers’s Under the Jacaranda 1903.

Did compo kill the carving star?

RZ: When composition [a malleable, mouldable material made from chalk, glue, resin and oil] took off, in London alone there were about 500 wood carvers who specialised in carving frames. By the end of the nineteenth century, there were only a handful left — and they were the best carvers, who could carve the reverse moulds used to create the compo ornament. With the move towards modernisation and mechanisation, a lot of traditional skills were unfortunately lost.

DB: In Europe, people were still carving traditionally for a lot longer. You get examples of English painters buying their frames from Italy, where they could still buy them at a reasonable price.

RZ: There were people — like William Morris, who was central to the Arts and Crafts movement — that rejected this whole modernisation of mass-produced goods. They looked for traditional frame makers and used them to design custom frames. This resurgence retained a lot of traditional frame-making skills, though the overall tide of mass production could not be reversed. The use of gold leaf became less common. Cheaper alternatives were employed such as imitation gold leaf, and bronze powders.

DB: I’m speculating, but it also provided a bigger range of frames on the market, from low-end to the very high quality, and everything in between.

Restoration reveals ornate rococo details carved into the pine frame for Romney’s Mrs Yates as the Tragic Muse, Melpomene 1771, QAG Framing Studio, October 2022 / Photograph: Chloë Callistemon, QAGOMA

Is this Mrs Yates’s original frame?

RZ: We can’t be 100 per cent certain that this is the original frame for George Romney's portrait of Mrs Yates. It is of the period — this is a British frame in the rococo style. (The rococo period in Britain was from around about 1740 to 1770.) At the time this work was painted — the early 1770s — tastes were changing from rococo to neoclassical. The flamboyance of shells, scrolls, flowers was replaced with a more refined and linear style. Though gold remained as a preferred surface finish. There are examples of early Romneys in frames similar to this, as well as Romneys in the neoclassical style. It was fashion: frames came off works, went on works — people chopped and changed all the time.

Frame-makers normally put a stamp or label on the back of the frame — sometimes a carved name or initial. The provenance of this frame could have been determined by such a label. To date we have not uncovered any evidence of this. What is known is the frame and painting are both British and stylistically appear to have been created in a very similar period.

It is not uncommon for frames to be removed from the paintings they were originally intended for. Artists such as James Whistler, who designed his own frames, wanted to prevent this from occurring; he understood the importance of the relationship between the frame and the painting. He painted his butterfly monograph on his frames, ensuring the frame would remain core to the painting. He was very much a pioneer in that area.