Transitions Now

Contemporary Aboriginal Forms and Images from the Collection

In ‘Transitions Now’, innovative textured and sculpted works from the Gallery’s Collection illustrate Aboriginal Australian artists’ ongoing commitment to declaring their identity and vital presence in contemporary society. In dynamic juxtapositions, individual and group artistic statements predominate over strictly held categories, demonstrating the immeasurable contribution Aboriginal artists continue to make to Australia’s visual arts culture.

Though often still inspired and nourished by ancient traditions, today’s responses may be entirely contemporary — expressed in fresh choices of narratives, materials and techniques utilising found and discarded materials or realised in new media.

‘Transitions Now’ displays work by artists from across the country, from the Tiwi Islands in the north to central Australia and the eastern states. Regardless of the materials they choose to work with, all the artists included draw on inherited knowledge and respect for their continuing living culture.

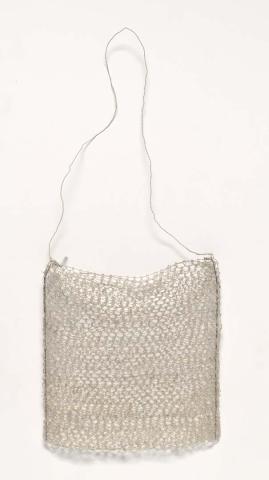

Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Lorraine Connelly-Northey transforms abandoned remnants of rural industry into contemporary works of art employing unusual combinations of found materials and traditional weaving techniques. Her works often take their title from the Waradgerie language name for string bag: Narrbong.

While early baskets were typically made from natural fibres, Connelly-Northey uses such harsh materials as barbed wire, a product used since colonisation to enforce private ownership and land partitioning. The artist explains her approach as a blending of the skills and attitudes of her parents: resourcefulness and thriftiness inherited from her Irish father, and traditional weaving inspired by her Aboriginal mother.

Narbong 2009

- CONNELLY-NORTHEY, Lorraine - Creator

Narbong 2009

- CONNELLY-NORTHEY, Lorraine - Creator

Narbong 2009

- CONNELLY-NORTHEY, Lorraine - Creator

Narbong 2012

- CONNELLY-NORTHEY, Lorraine - Creator

Narbong 2012

- CONNELLY-NORTHEY, Lorraine - Creator

Narbong 2012

- CONNELLY-NORTHEY, Lorraine - Creator

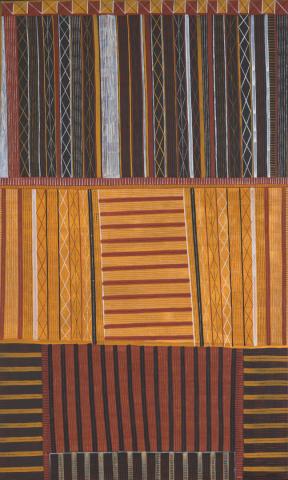

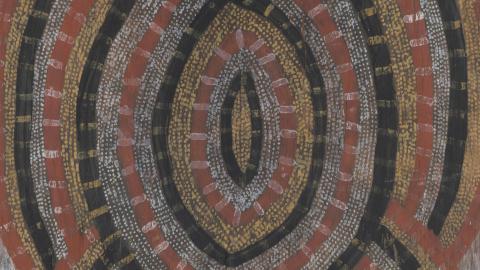

Kayili car bonnets

The Kayili were amongst the last nomadic desert peoples forced into settled life, eventually inhabiting Patjarr, a small community in the heartland of the Western Desert a thousand kilometres west of Alice Springs. The first white people they saw arrived by car and now the desert abounds with cars — some functional, many in various stages of decay.

The Kayili artists have given these resurrected car bonnets new life, painting them with an intensity that reflects their urge as tradition-bearers to constantly invent new ways to record their culture and portray their desert world. They indulge a love of colour by animating the metal surfaces with shimmering, cryptic, topographical maps of their country and the ancestral journeys that formed it.

There’s a beautiful irony in these painted wrecks having new life and travelling back to cities where they came from.

Valiant 2007

- GILES, Jackie Kurltjunyintja - Creator

Holden 2007

- CAMPBELL, Nola - Creator

Toyota 2007

- DAVIES, Pulpurru - Creator

Nissan 2007

- WARD, Mrs Kumana - Creator

Toyota HiLux 2007

- GIBSON, Mary - Creator

Michael Riley

In Sacrifice (portfolio) 1993, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Michael Riley (1960–2004) mines the reservoir of Christian iconography to proffer an allegory of Indigenous sacrifice under colonisation. In this series, images of crosses, fish, lilies and stigmata function not only as Christian symbols, but as symbols that narrate sacrifice.

During colonisation, Christian organisations exerted control over Indigenous peoples by establishing reserves and missions. Many were forcibly relocated to these missions and forbidden from speaking their language and participating in cultural practices. Having grown on up on the Talbragar Reserve just outside of Dubbo, NSW, Riley witnessed this firsthand. Ultimately, Riley intended not to disparage Christianity as a practice, but to critically examine how it was weaponised.

VIDEO: Learn more about Michael Riley's practice.

Note: During the course of 'Transitions', Sacrifice (portfolio) was rotated with cloud (portfolio).

Sacrifice (portfolio) 1993

- RILEY, Michael - Creator

cloud (portfolio) 2000

- RILEY, Michael - Creator

Gunybi Ganambarr

Since the early 1970s, a massive conveyor belt has exported bauxite from the mine at Melville Bay, where it was loaded onto bulk carriers. The conveyor was once the longest in the Southern Hemisphere and its rubber required regular replacement. Discarded lengths have been put to multiple uses in the local community — in 2006, Gunybi Ganambarr began incising ancestral narratives into sheets of bark. He was the first artist of his peers to experiment with novel materials and to see the creative potential for the lengths of heavy black rubber. Ngaymil 2015 is his most ambitious work to date.

Though a departure from the conventional materials used in the region, Ganambarr re-examines the age-old tenets set by his elders to ‘use only materials from the environment to make art’ to include working with materials abandoned on his lands — a healing process in response to a fractured history with the local mining enterprise that has seen endless tonnes of his ‘mother earth’ transported off-shore to be processed.

Nganmarra 2015

- GANAMBARR, Gunybi - Creator

Ngaymil 2015

- GANAMBARR, Gunybi - Creator

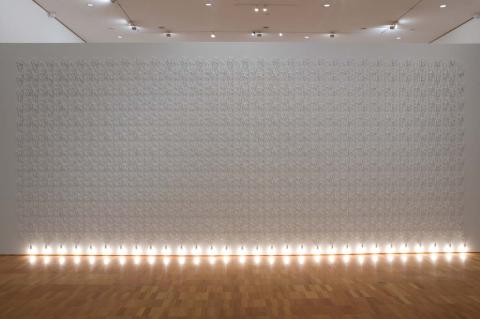

Jonathan Jones

lumination fall wall weave 2004–06

Jonathan Jones has thoroughly researched his Koori heritage through studying early writings and museum collections. The communal activity of Aboriginal net-making inspired him to interpret these patterns in light installations seen here, and in other works sewn onto paper using his mother’s vintage hand-turned sewing machine.

In lumination fall wall weave Jones has created a conceptual framework for human connectivity: the electricity pulses through its woven cables to create one entity, with the interplay of light operating as a metaphor for community. Though electricity is identified with urbanisation, the way Jones uses light may also recall memories and guiding spirits that linger long after the demise of the physical body.

untitled (domestic heads or tails) 2009

Jonathan Jones’s work is often elliptical but always thought-provoking in its approach to the ways that Indigenous cultural heritage is experienced in contemporary life.

untitled (domestic heads or tails) cannot be taken at the face value of its title. Characteristically, Jones alludes to an earlier image of Aboriginal occupation of the land, as curator Stephen Gilchrist explains: ‘The cylindrical objects which comprise Jones’s installation untitled (heads or tails) 2009 mirror the truncated forms of de-stumped marayanang or scar trees’.

This work was inspired by an image of Tasmanian Aboriginal people made by an artist on one of the early French exploration voyages in 1792–93. For Jones, trees have a certain emotional reticence that allows one to consider not only the past but the future: as Gilchrist notes:

‘A scar is suggestive of both wound and repair, and Jones’s installation pivots on this poetic dichotomy.’

Further works in ‘Transitions: Now’

Milngurr 2018

- MARIKA, Dhuwarrwarr - Creator

Mindirr 2012

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Mindirr 2012

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Mindirr 2012

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Mindirr 2012

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Mindirr 2012

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Mindirr 2012

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Kulama 2012

- COOK, Timothy - Creator

Thap Yonk 4 2018

- NGALLAMETTA, Joel - Creator

Larrakitj 2017

- WANAMBI, Mr. W. - Creator

Larrakitj 2017

- WANAMBI, Mr. W. - Creator

Wawurritjpal (Larrakitj) 2017

- WANAMBI, Mr. W. - Creator

Tutini 2011

- COOK, Timothy - Artist

- PURUNTATAMERI, Patrick Freddy - Carver

Tutini 2011

- COOK, Timothy - Artist

- PURUNTATAMERI, Patrick Freddy - Carver

Tutini 2011

- COOK, Timothy - Artist

- PURUNTATAMERI, Patrick Freddy - Carver

Lorrkon (Burial pole) 2006

- DURRNG, Mickey - Creator

Bathi Mul 2018

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Bathi Mul 2018

- RARRU, Margaret - Creator

Guutu (vessel) 14 2001

- MACNAMARA, Shirley - Creator

Spinifex and Peach 2019

- MACNAMARA, Shirley - Creator

Cu 2016

- MACNAMARA, Shirley - Artist

- MACNAMARA, Nathaniel - Assistant

Ningher (reed canoe) 2020

- GREENO, Rex - Creator

Burial basket 2018

- KOOLMATRIE, Yvonne - Creator

Bi-plane 2006

- KOOLMATRIE, Yvonne - Creator

Unnamed 2009

- HARDING, D - Creator

Mat 2004

- BAYPUNGALA, Judy - Creator

Feature image: Mary Gibson / Ngaanyatjarra people; Australia, b.1952 / Toyota HiLux (detail) 2007 / Purchased 2008. The Queensland Government's Gallery of Modern Art Acquisitions Fund / © Mary Gibson

Digital story context and navigation

TRANSITIONSExplore the story

Digital Story Introduction

TRANSITIONSMichael Riley: Sacrifice and cloud (portfolio)

Read digital storyAbout this page

Related resources