The artists of ‘Transitions: Now’ do not discount the historical importance of materials — their guarantees, spoils, debates or provocations — but rather ask us to bear witness to their personal, communal and creative licences.

— Adam Ford

Authenticity and exchange

Aboriginal artists have long had to contend with the prescriptions of Western art and its institutions in the demarcation of their artistic and cultural productions. Such prescriptions have, in particular, related to the impact that external influences have had on artists and their choice of materials. Encumbered by debates around ‘authenticity’, Aboriginal art has long contended with notions of external influence and cross-cultural exchange as a patently corrupting force.

These debates have called into question the influences of anthropologists, cross-cultural trade and the art market on Aboriginal artists and their choice of materials. In one example, debates raged around whether artistic designs that historically had been produced ephemerally and in situ, such as in rock galleries, remained art — or even were art — when painted on portable media such as bark and introduced for commercial sale. The same ‘authentic turn’ followed when some artists began to move their designs from bark to canvas, echoing the social changes occurring in their lives.

Material translations

Realised in ‘Transitions Now: Contemporary Aboriginal Forms and Images from the Collection’ is the instinctual and pragmatic sense with which materials have been used by the artists to translate cultural knowledge and practices into contemporary forms. By using materials that span organic matter, reclaimed detritus and readymade objects, the artists mark the assurance of cultural continuity in the contemporary era. Excited by old, new and hybrid ways of artistic and cultural production, the primacy of materials is here showcased.

Many of the of the media and materials used by the artists emerge from the junctures of cross-cultural exchange; they include canvas paintings, photography, fluorescent light tubes, rusted steel, burnt tin, copper and conveyor belt rubber. In this way, the notion of authenticity presents itself as unstable demand.

According to Dr Elizabeth Coleman, ‘cultural authenticity’ invokes the mythos of ‘organic wholeness’ and suggests the ‘possibility of a “pure” culture “uncontaminated” by external influences’.1 When applied to the cultural or artistic production of Aboriginal artists, the notion of cultural authenticity reveals itself to be an inherently ethnographic ideological framework that, as Larry Shiner posits, requires the presence of an ‘unspoiled, pre-contact native’ who ‘live[s] in another time than our own’.2

The notion of an authenticity borne out of a culture ‘uncontaminated’ by external influences is demonstrably inconceivable throughout this show — for such is the effect of colonisation.

Reclamation

An overarching commonality across artists’ chosen materials is the use of reclaimed detritus or readymade objects. Kayili artists Nola Campbell, Pulpurru Davies, Mary Gibson, Jackie Kurltjunyintja Giles and Mrs Kumana Ward paint vibrant traditional designs on car bonnets (Holden, Toyota, Toyota HiLux, Valiant and Nissan) reclaimed from the red-dusty desert.

Reclaiming the natural environment around him, Pakana artist Rex Greeno uses plant fibres to recreate ningher (reed canoe) to demonstrate his knowledge of ancestral engineering.

In contrast, the works of Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones repurpose readymade fluorescent light tubes and electric cables to assemble ambitious illuminated displays. In untitled (domestic heads or tails), Jones’s compacted illuminous vessels reference marayarrang (Koori-carved scar trees), demonstrating the subtlety with which unconventional materials can be used.

Subtle statements arise also in the textured and incised surfaces of Yolŋu artists Gunybi Ganambarr and Dhuwarrwarr Marika, and Bidjara/Garingbal/Ghungalu artist d harding. In Ngaymil — the name of his clan grouping in Yirrkala — Ganambarr etches zigzagging and herringbone clan designs into conveyor-belt rubber. In Nganmarra, he incises these same clan designs into a polished galvanised steel water tank. With community approval, Ganambarr translates traditional knowledge and customs into contemporary forms. Referring to the materiality of reclaimed objects, these works — like Marika’s Milngurr and harding’s unnamed — perhaps pull a sensory experience of materials (here, touch) into focus.

In Milngurr, Marika paints a sacred waterhole from an ancestral story belonging to her Dhuwa moiety in thick swirls of enamel paint upon aluminium panel.

In unnamed, d harding fashions from lead and steel wire a simulacrum of a nineteenth-century ‘king plate’ that is inscribed with the alphanumerical identifier ‘W38’. Historically worn around the neck, harding’s rusted cast-iron crescent manifests the codification of Aboriginal peoples by colonial authorities. harding highlights an embodied and sensory experience of colonial materiality and situates it within the contemporary era as a corroded reminder of colonialism’s continued presence.

Weaving story

That materiality might be understood through the sensory experience of touch is further emphasised by the strong showcasing of woven works. Metals, particularly, such as in the works of Lorraine Connelly-Northey and Elisa Jane Carmichael, show skilful ductility. Ngugi woman Carmichael fashions delicate silk-coated wire bags according to ancestral Quandamooka weaving techniques that she has helped revive and continues to preserve alongside other women in her family. Carmichael’s woven works incorporate both traditional and contemporary techniques through which she honours her saltwater heritage.

Similarly, although perhaps more abrasively, Waradgerie (Wiradjuri) woman Connelly-Northey forages scrap metals such as barbed wire and bed springs from creeks and farmlands to fashion narrbong (string bags) in works of the same name. Both Carmichael and Connelly-Northey use Aboriginal weaving techniques to suggest culturally continuous connections to materials, their Countries and their heritage.

(l–r) Lorraine Connelly-Northey / Waradgerie people / Australia b.1962 / Narrbong (String bag) 2008 / Rirratjingu people / Purchased 2008. The Queensland Government’s Gallery of Modern Art Acquisitions Fund / © Lorraine Connelly-Northey; Elisa Jane Carmichael / Ngugi people / Australia b.1987 / We see your hands guiding us to bring our weaving alive (3) (details) 2008 / Purchased 2019 with funds from Cathryn Mittelheuser AM through the QAGOMA Foundation / © Elisa Jane Carmichael/Copyright Agency

Margaret Rarru’s Mindirr works continue the influence of woven receptacles but with a greater emphasis on organic materials. The Liyagawumirr artist uses specially formulated black dye to colour her pandanus palm baskets, which are said to be carried by the ancestral Djan’kawu sisters on their journeys across Arnhem Land.

Woven also with pandanus palm, Wurlaki woman Judy Baypungala’s Mat offers a sprawling display of concentric circles and is wispily fringed along its circumfrence. Mat, if taken to refer to a material upon which people sit or rest, reflects the sense of utility that these woven forms suggest. Comparably, Yvonne Koolmatrie’s Burial basket and Burial basket (with handle) are profound representations of the final resting place for her Ngarrindjerri peoples and contrast the buoyant whimsy of her sedge grass hot-air balloon and eel trap sculptures.

Meanwhile, Indjalandji/Alyawarr woman Shirley Macnamara’s woven spinifex vessels are made from a variety of zoic materials, including emu feathers, horse hair and echidna quills. A divergence in Macnamara’s work Cu sees her using intertwined copper coils to reference the deep holes left by abandoned copper mines on her family’s property in north-west Queensland.

(l–r) Margaret Rarru / Liyagawumirr people / Australia b.1940 / Mindirr (details) 2012 / Purchased 2012 with funds from an anonymous donor through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / © Margaret Bilinydjan Rarru/Copyright Agency; Yvonne Koolmatrie / Ngarrindjeri people / Australia b.1944 / Burial basket (with handle) (details) 2017 / Purchased 2019 with funds from Cathryn Mittelheuser AM through the QAGOMA Foundation / © Yvonne Koolmatrie

Ritual foundations

Alongside weaving, there appears a significant showcasing of forms that draw their materiality from ceremony and ritual. Materials in this sense are understood not merely according to their physical properties — although this is made no less incidental — but as possessing potent spiritual and metaphysical charges.

Tiwi artists Pedro Wonaeamiri and Timothy Cook imbue their own artistic approaches to paint and carve (respectively) the towering tutini funeral poles of Tiwi mortuary ceremonies. Both demonstrate the ability of contemporary artists to work according to traditional cultural practice without forgoing their own creative licenses.

This is evidenced also in the larrikitj (memorial poles) of Marrakulu/Dhurili man Mr W Wanambi, which hum with a quiet gravitas. His sense of materiality is understood in the selection of base timbers he chooses — naturally cracked and imperfect — and contrast the intricacy of their external designs. While inspired by Yirrkala customs and conventions, Wanambi’s poles can be taken as instances of a contemporary sculptural practice that retains the spiritual and metaphysical potency of its materials.

Liyagalawumirr man Micky Durrng’s Lorrkon (Burial pole) connects similarly to Wanambi’s larrikitj — given both terms find overlapping usage and meaning in Arnhem Land. Lorrkon burial poles customarily contain the ochred remains of the deceased and are buried into the ground, where they are left exposed to the elements.

In his work, Durrng represents aspects of important ceremonial body paintings associated with his Djang’kawu ancestors as they travelled from the east through his clan lands south of Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island). These designs were painted also on the body and signify the embodied materiality of ceremony, cultural stories, and traditional practices.

Artists such as Durrng, Wanambi, Cook and Wonaeamiri mark the assurance of cultural continuity by insisting upon the contemporary relevance of ceremony and ritual. Their materials lose none of their spiritual or metaphysical charge, while maintaining the personal, communal and creative licences of their practices.

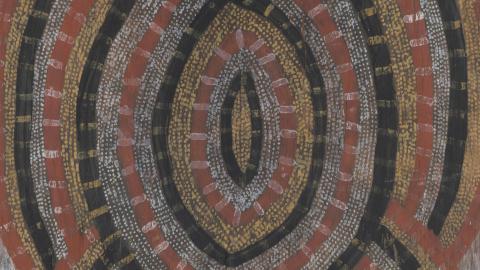

The transference of traditional and ceremonial design continues in the work of Tiwi woman Raelene Kerinauia. Kerinauia makes use of kayimwagakimi (Tiwi painting comb) to create her own jilamara (‘good design’), where dots in refined rows are intricately crosshatched to fashion geometry from Tiwi cosmology.

Similarly, Thap Yonk 4 — by the late Kugu Uwnah and Wik senior cultural leader Mr Ngallametta Jr — builds on the works produced by his father, who is credited as the first Wik or Kugu artist to translate their sculptural and body painting traditions into canvas paintings. Thap Yonk (Thap Yongk) refers to the customary mortuary poles buried into the ground around the interred body of the deceased. Taken as upturned trees, these poles branch underground, where their symbolic root system and implied canopy absorb the spirit as it passes back into the earth.

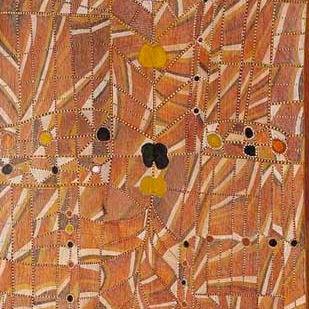

Over six panels, Ngallametta alternates bands of red-brown ochre and white clay, with each panel showing slight variations in the Wanam clan design. These designs are repeated and reiterated on the Thap Yongk poles to create culturally continuous spiritual and material links.

The photographic works of Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Michael Riley mark the assurance of cultural continuity through the memorialising function of photography. Although both series were produced prior to the advent of digital photography, their conceptuality and vibrant rendering afford them currency in the digital era. In terms of materiality, both Sacrifice (portfolio) and cloud (portfolio) show a noted care and understanding of the mechanics of film photography. In addition, each series preserves the material objects and the cultural and symbolic economies it depicts.

In Sacrifice (portfolio), Riley mines the reservoir of Christian iconography to proffer an allegory of Indigenous sacrifice on Aboriginal Missions, whilst in the surreal cloud (portfolio) series, he locates Indigeneity, Western religion and the materiality of objects such as the Bible within a broader schema of contemporary society. The material and spiritual links he makes, not unlike those made in the memorial poles, show cultural reverence — inasmuch as they commit to a personal, communal and creative licence.

The potency of materials and the instinctual and pragmatic sense with which they have been used connects the practices of these artists. At once, materials compliment, contrast, coalesce and offer wildly different points of engagement with each viewing.

The artists of ‘Transitions: Now’ do not discount the historical importance of materials — their guarantees, spoils, debates or provocations — but rather ask us to bear witness to their personal, communal and creative licences.

Against the colonial imagination, which has sought to emphasise Indigenous culture as fixed and stagnant, these artists evidence a capacity to translate cultural knowledge and practices into contemporary forms. Their works are not burdened by polemics of authenticity; rather, they are empowered by assurance of cultural continuity in the contemporary era.

The primacy of materials is here revealed — here opened — in what demonstrates the immeasurable contribution Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists continue to make to Australia’s visual arts landscape.

Adam Ford is Assistant Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA.

Endnotes

1. Elizabeth Burns Coleman, ‘Aboriginal Painting: Identity and Authenticity’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 59, no. 4, Fall 2001, p.386.

2. Larry Shiner, ‘“Primitive Fakes”, "Tourist Art”, and the Ideology of Authenticity’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 52, no. 2, Spring 1994, p.229.

Digital story context and navigation

TRANSITIONSExplore the story

About this page

Related resources