APT8 and Mongolian painting

By Reuben Keehan

Artlines | 1-2015 |

APT8 marks the beginning of the Gallery’s engagement with Mongolia, with the inclusion of works by four young Mongol zurag painters who have revived a national cultural tradition by applying it to their own experiences in a rapidly changing society.

Characterised by its ultra-fine brushwork, bright colours, flattened perspective and themes drawn from everyday life, zurag is derived from Tibetan thangka painting, synthesising elements of Chinese guohua painting and the medieval equestrian art of the Khitan people. In this sense, it shares its heritage with many traditional and contemporary art forms, ranging from Persian miniatures to Chinese landscapes and Japanese nihonga painting. The most celebrated example is Balduugiin Sharav’s classic work One day in Mongolia 1911, which hangs in Ulaanbaatar’s Zanbazar Museum of Fine Arts.

After the Mongolian revolution of 1921, zurag focused on themes of secular nationalism, merging with the socialist realist painting that would dominate Mongolian culture from the bloody Stalinist purges of 1930s until the advent of democracy in the early 1990s. Since that time, Buddhist iconography and shamanic images have made an appearance, as they have in post-communist Mongolian culture more broadly. Established as a subject at the Mongolian University of Arts and Culture in the late 1990s, zurag has since been taken up by a passionate new generation of artists who find within it the means of addressing the tensions of daily Mongolian life.

Drawing on traditional patterning and the experiences of Mongolian women, Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu’s paintings combine poetic and everyday imagery, creating subtle contrasts between the manufactured and the natural or organic, and between intense detail and flat planes of colour. The graphic and symbolic qualities of Uuriintuya’s paintings are particularly pronounced, with the inclusion recognisable motifs from traditional Buddhist painting — and East and Central Asian aesthetics in general — as well as psychologically charged imagery of contemporary life.

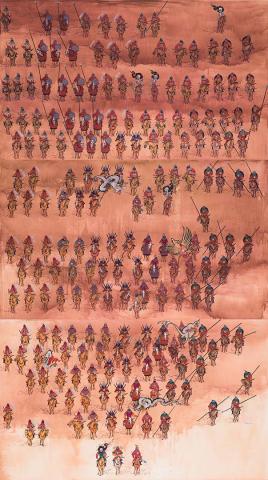

Gerelkhuu Ganbold brings a searing dramatic sensibility to zurag painting, producing mural-sized canvases of swirling battle scenes that recall contemporary comics and science-fiction cinema, along with traditional epic painting and the Mongolian genre of equestrian art. Of particular interest to Gerelkhuu is the free and open composition that zurag offers, with an absence of vanishing-point perspective allowing all pictorial elements to be rendered with equivalent detail. His paintings of the famed mounted warriors of the Mongol Empire allegorise life in present-day Mongolia, which the artist characterises as an eternal battle, a daily struggle for money and food while the powerful fight among themselves for influence.

Of the four artists represented here, Nomin Bold is the most emphatic in her employment of the composition, materials and techniques of thangka painting. Also notable is her use of collaged pages from Mongolian scriptures and gold-leafing, which ground her extremely fine brushwork and dynamic composition. Her stylised renderings of deities, human and animal figures, and the labyrinthine landscape of Ulaanbaatar offer a satirical edge with an ultimately uplifting tone.

Baatarzorig Batjargal’s zurag paintings also possess a strong element of social criticism, betraying the influence of Chinese political pop in their use of recognisable historical figures and their juxtaposition of traditional and consumerist imagery. Aesthetically distinguished among contemporary zurag paintings by their fine shading and unusual surfaces, which are often sourced from rural furniture, they are particularly concerned with the loss of traditional heritage through a succession of regimes, from the ascetic culture of Soviet-style communism to the rising inequalities and empty consumerism of US-style capitalism. Batjargal brings epic composition and satirical humour to the serious content on his work.

These paintings, by four of the most inventive practitioners of contemporary zurag, are a fine introduction to some of the key themes and techniques in the art being produced in Mongolia, one of the most exciting new cultural contexts in Asia.

Read more about Contemporary Mongolian art in QAGOMA’s Asia Pacific Art Papers (2021).

Connected objects

Tumbash model XQ 2014

- DAGVASAMBUU, Uuriintuya - Creator

Unnamed energy 2014

- DAGVASAMBUU, Uuriintuya - Creator

Path to wealth 2013

- DAGVASAMBUU, Uuriintuya - Creator

Tomorrow 2014

- BOLD, Nomin - Creator

Labyrinth game 2012

- BOLD, Nomin - Creator

Nomads 2014

- BATJARGAL, Baatarzorig - Creator

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject