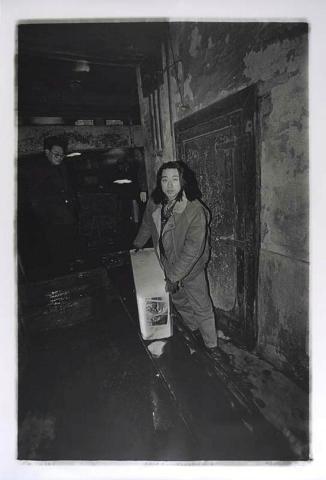

Wang Jin: Robe 1999

By Reuben Keehan

Artlines | 3-2011 | September 2011

Robe is a very early example of a major body of work that occupied Wang Jin for the most part of a decade. In these works the iconic form of the Peking Opera robe is rendered in transparent plastic embroidered with fishing line. Continuing visual and conceptual themes explored in his 1996 performance Ice 96 Central China, the juxtaposition of a traditional high-cultural form and modern synthetic material in Robe refers to transformations in Chinese society, most pointedly the rapid evolution of consumerism.

'Wang is one of a generation of artists who grew up in the period during which China opened diplomatic and trading relations with the West', explains Abigail Fitzgibbons. They witnessed China's widespread embrace of economic reforms which has resulted in an extraordinary boom in large-scale building developments. In all of his projects, Wang Jin pays attention to the location or site of his works, and his interventions in these areas are dense with symbolic or historical associations.1

Plastic, for Wang, is the material that most succinctly represents the contradictions of contemporary society: cheap and versatile; omnipresent and environmentally unfriendly; or, as the artist has put it, 'high tech junk'. While producing such a revered article of traditional culture from such a vulgar fabric might be understood as a metaphorical act of profanation, the object itself retains a haunting beauty, one that could only be produced by the use of such a luminous surface to construct what remains a form of undeniable elegance. This suggests that the relationship between tradition and modernity is more complex than a process of sequential displacement, where an older tradition makes way for a new one. In this sense, the forces at work in a rapidly transforming Chinese society, which include competing desires for material wealth, the security of tradition and the sanctity of interpersonal relationships, deserve careful and ongoing attention.

These tensions and their effect on human behaviour were first explored by Wang Jin in Ice 96 Central China. The artist had installed a wall of ice bricks, all containing consumer objects in front of a new department store. When a crowd that had gathered spontaneously began destroying the bricks, Wang was both surprised and fascinated, and documented the crowd'ss actions extensively. Robe is part of an ongoing effort to understand these forces, reproducing both the transparency and the consumerist focus on the earlier work, while introducing the material longevity of plastic and the enduring elegance of traditional Chinese design. As Wu Hung has noted, 'By making the costumes transparent, [Wang] is able to define this culture as both there and not there. They copy traditional drama costumes but actually make the models disappear'.2

Endnotes

- Abigail Fitzgibbons, Collection documentation, 'Wang Jin, Ice 96, Central China', July 2007.

- Wu Hung, Transience: Chinese Experimental Art at the End of the Twentieth Century [exhibition catalogue], David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Chicago, 1999, p.159, as quoted in The China Project [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, 2009.