Dialogue and exchange

By Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow Ineke Dane

International galleries February 2024

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, creative exchange between France and Japan had a profound effect on art and design — and sparked the development of entirely new aesthetic movements.

In 1854, Japan reopened to the world after more than 200 years of near isolation. The global market for Japanese creative production expanded rapidly: screens, ceramics, textiles and prints all became hugely popular.

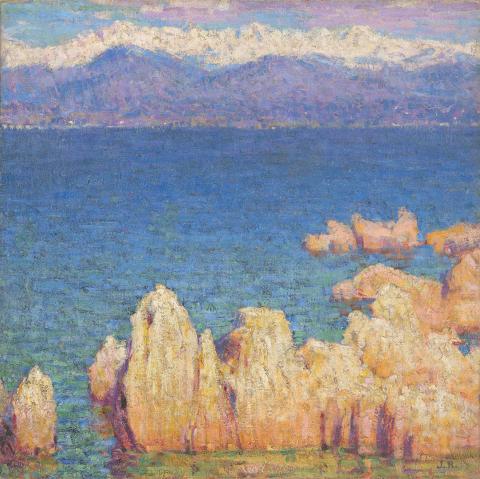

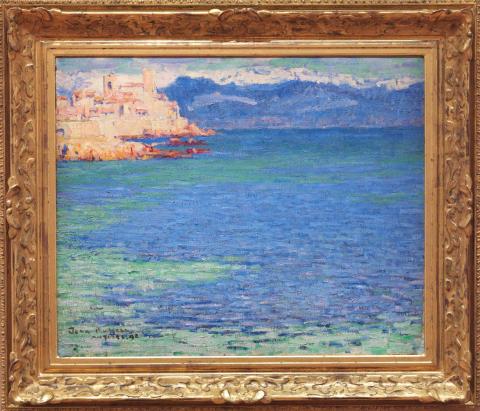

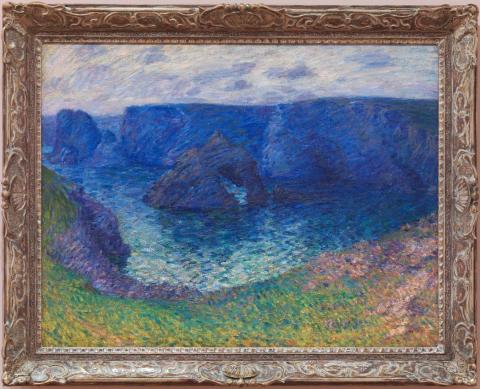

European artists were captivated by the Japanese woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e, meaning ‘pictures of the floating world’. Characterised by flat areas of colour, defined outlines, cropped, asymmetrical compositions and a lack of horizon lines, these prints often featured everyday scenes. French artists, in particular, were greatly excited by these alternative ways of representing the world. Early forms of photography further encouraged artists to capture fleeting moments of daily life often absent in more formal academic traditions. This style of painting came to be known as Impressionism.

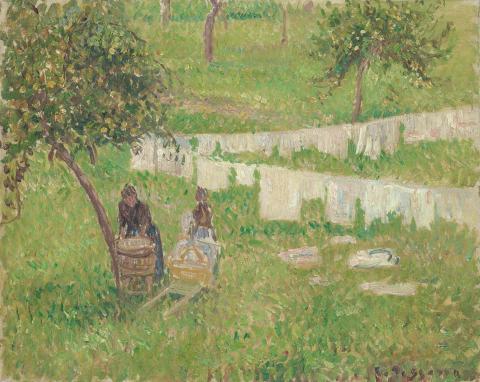

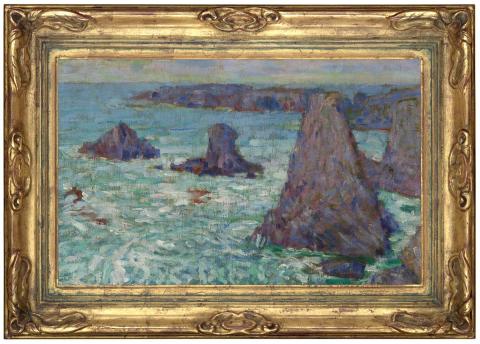

For the Impressionists, Japan represented a departure from ‘the West’ and all that was familiar — a dreamlike, remote place that few of them would ever visit. Instead, artists such as Camille Pissarro, John Russell and, later, Pablo Picasso, sought the beauty of the natural, pre-industrial world in the countryside.

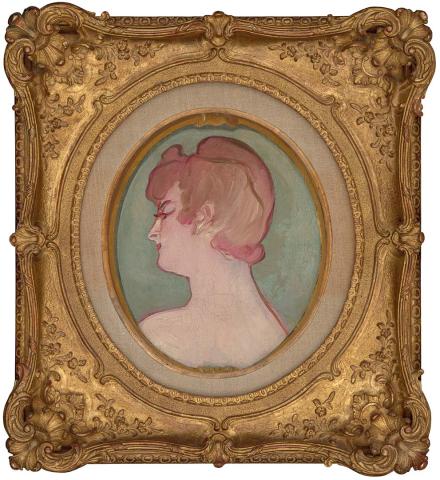

By contrast, Edgar Degas and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec focused on the rapidly modernising city of Paris, with its dance halls, cafes, theatres and brothels, depicting young ballerinas, singers and cabaret performers. By the end of the nineteenth century, Paris was a vibrant cultural centre to which artists, writers, publishers and art dealers flocked, adding to the energy of the city.

Connected objects

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject