Two men dreaming: A Pintupi masterpiece

By Simon Elliott Sophia Nampitjimpa Sambono

Artlines | 2-2024 | June 2024

A significant work with a storied past, which sparked some controversy over its intense cultural importance, is now part of the Josephine Ulrick and Win Schubert Charitable Trust Collection. Here, Simon Elliott and Sophia Nampitjimpa Sambono expand on the meaning of painting created by one of the founders of the Papunya Tula Artists collective, Tommy Lowry.

All the experts agree, as do I, on the significance of Tommy Lowry’s Two Men Dreaming at Kulunjarranya in terms of its artistic and aesthetic merits: there is no doubt the painting is a masterpiece.1

— Wally Caruana

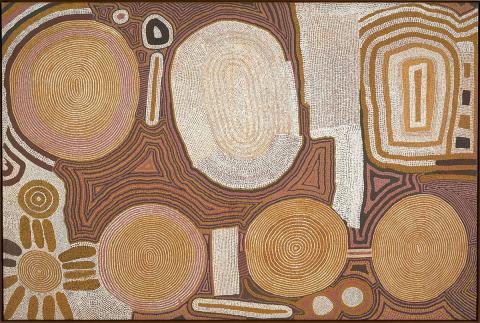

The large canvas Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya 1984 by Patjarrngurrarra Tjapaltjarri Tommy Lowry — better known after European contact as Tommy Lowry Tjapaltjarri, or simply Tommy Lowry — is widely considered to be the artist’s greatest work and ‘one of the pinnacles of Pintupi painting in the 1980s’.2 Lowry’s deep ancestral knowledge borne from a life spent on Country, along with a talent for formal artistic innovation, provided him with an extraordinary confidence that enabled him to depict epic Dreaming narratives with a rare majesty and structure, and earnt him a significant place in the history of contemporary Australian art. Pointing to its rare and exceptional status, Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya became a cause celebre when it was denied a permanent export permit by the Commonwealth Government due to its significance to Australia’s cultural heritage, after being sold at auction to prominent New York–based collectors John and Barbara Wilkerson in 2007.3

Lowry’s relatively small body of work — having produced only 43 works for Papunya Tula, on record — is representative of both the genesis of the Western Desert art movement and its transformation. A founding board member of the seminal artists collective Papunya Tula Artists based in Central Australia, he initially produced wood carvings for the collective before painting sporadically through the 1970s in classic multilayered and iconographic Western Desert styles. As described by leading First Nations curator Hetti Perkins, his ‘intricately detailed and optically dazzling Western desert paintings’4 are ‘an expression of the nexus between ceremony and country’5 giving visual form to the Tjukurrpa, or inherited ancestral Dreamings, of the artists.

Created in the remote and makeshift conditions at Kintore in the Northern Territory, Lowry set to work on a substantial piece of expensive Belgian linen, 120 x 180cm, supplied by astute arts manager Daphne Williams.6 What resulted was a work that condenses ‘the complex narratives which characterised his paintings in the mid-1970s’ into innovative motifs that resemble enlargements of sections with ‘distinctive creamy, pulsating surfaces in the dotting’, which generate an illusion of movement.7

Epic narrative of the Wati Kutjarra

Traversing Country from the Great Australian Bight, through the Great Victoria Desert to the Gibson Desert, and towards the northwest coast of Western Australia, the Wati Kutjarra (Two Men Dreaming) is one of the longest and most significant songlines in Aboriginal Australia’ and ‘one of the greatest of Australian epic narratives’.8 The episode depicted in Lowry’s work centres on the Wati Kutjarra themselves, often described as Ngangkaris or traditional Aboriginal healers but far from benevolent; men just old enough to be initiated but who still act in the unpredictable ways of children. They also possess the magical quality of sorcerers and doctors. So, while they are too young to have the full law in their head, they have a capacity to do extraordinary things — good and bad.9 When the Wati Kutjarra made camp south‑west of Kintore, they found some minykulpa (very strong native tobacco, illustrated in the lower left corner of the painting) and proceeded to consume the plant atop a tali (sandhill). The minykulpa was so powerful that the young men ‘died’, sprawled out on their backs with their legs wide apart on the sand. In this state, their bodies released urine in a torrent so strong that it saturated the ground, forming the great salt lake Kumpukurra (literally, ‘bad urine’). After the lake was formed, the Wati Kutjarra came back to life and continued their adventures.10

John Kean, a former art advisor to Papunya Tula Artists (1977–79), draws parallels between Lowry’s choice to depict this specific moment in the expansive narrative and his approach to life.11 The artist, who eschewed life in white settlements, is said to have admired the ‘wild, uncontrolled and somewhat antisocial’ personalities of the two young men in his painting. Although revered as charismatic and eminent heroes ‘filled with magical power’, who traversed Country ‘destroying many threatening demons’, they could also be ‘lustful, vengeful, indulgent and erratic, just as young men are to this day’.12 Lowry himself met an untimely death at the age of 52, when he was shot and killed during a card game at Kiwirrkura in December 1987.13 His affinity with the impulsive protagonists is powerfully captured within the work, creating an allure that arguably goes beyond its compositional excellence. As Kean writes:

The exceptional quality of Kuluntjarranya does not arise from a seamless resolution of pictorial challenges, or the painting’s overall schematic perfection . . . Rather, its captivating presence results from the work’s unruly energy — a true encapsulation of the capricious youthful vigour of the Wati Kutjarra. The tension between the six bustling forms and the agate-like negative spaces, compressed between those giant orbs, ensures that Kuluntjarranya is never stable. Each object is created in the moment and insists on its own centrifugal energy.14

The events depicted in Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya occurred on the artist’s grandfather, father and uncle’s Country. The sites where these family members died and were buried are represented by the other sets of concentric circles. By representing these sites and their relative geographical relationship, Lowry combines events of the ‘creative era’ with those of his extended family into a ‘holistic unity’.15

Return to Country

Tommy Lowry’s most significant works were produced from 1983 to 1987, the four years prior to his death.16 This intense period of creativity coincided with the most dynamic phase in the resettlement of the Western Desert, also known as the outstation movement, which ‘crystallised and energised’ painting within Papunya Tula Artists more broadly.17 The Papunya Tula paintings of this era are described as ‘electrifying symbols of cultural affirmation’, and even as visual expressions of ‘cultural emancipation and self-determination’.18 Painted in early 1984 at the settlement of Kintore (the same year Lowry joined the newly established Kiwirrkurra community), Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya ‘encapsulates the excitement when the Pintupi made a heroic return to their desert homelands’.19

During this same period, contemporary art by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists became more widely recognised within the Australian art canon, with Papunya Tula at the forefront. Having been highly contested as contemporary art by the broader domestic and international art world, which was ‘raised on the ethnocentric and historicist blinkers of European modernism’,20 perceptions radically shifted following several high-profile exhibitions. Western Desert art, including Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya, was showcased in the landmark 1988 exhibition ‘Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia’, which toured the United States as the first major introduction of Australian Aboriginal art to North American audiences. ‘Dreamings’ is now regarded as turning point in the reframing of First Nations Australian art as contemporary art, transforming the perceptions of the international art market and reverberating in the Australian mindset.21 Lowry, in particular, is credited for changing the opinion of influential Australian art critic Elwyn Lynn. Initially being very wary of the art, the critic praised the optical brilliance of Lowry’s work in an 1988 review: ‘. . . at first glance we are subjects of Bridget Riley’s vertigo . . . you don’t need to know the tribal legend in order to perceive the aesthetic vibrations any more than you do the particular features of theosophy that helped stimulate abstractions by Kandinsky and Mondrian’.22

Denial of Commonwealth Export permit

In 2007, Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya sold at a record-breaking price to New York-based collectors John and Barbara Wilkerson, but the work was controversially denied a permanent export permit. This only served to cement its significance to Australian art. Despite the work having been painted for market, the members of the Papunya Tula Reference Group, a committee of the Commonwealth Government’s Moveable Cultural Heritage Panel for the Department of Environment and Heritage (which included Hetti Perkins, Vivien Johnson and John Kean), determined its significance to Australia’s cultural heritage as being on par with the earliest Papunya Tula boards, for which the legislation was originally created.23, 24 In Kean’s estimation, the controversy surrounding Lowry’s Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya has assumed a life of its own ‘beyond the epic narrative recorded on its surface’.25 The work was subsequently granted a temporary touring permit and became a focal work in ‘Icons of the Desert’, a high-profile exhibition that toured the United States.

Prior to the artist’s death, Kean declared that Tommy Lowry Tjapaltjarri ‘was actively changing the face of Western Desert art’ and was lamentably unable to explore his full potential as suggested in this prescient ‘work of visual power and compelling material presence’.26 Nevertheless, ‘the painting’s extraordinary history, together with its palpable cultural and artistic merit elevates it into the canon of Australian art’.27 Revered as an enduring symbol of the painting phenomena that emerged in Papunya Tula, Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya continues to captivate the art world nearly half a century on. It is fitting that such a great work has been acquired through the support of The Josephine Ulrick and Win Schubert Charitable Trust, for the Gallery.

This text was compiled and edited by Simon Elliott, Deputy Director, Collection and Exhibitions, QAGOMA, and Sophia Nampitjimpa Sambono (Jingili), Associate Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA, acknowledging foundational texts by John Kean.

Endnotes

- Indigenous art specialist Wally Caruana’s correspondence with Simon Elliott, 3 December 2021.

- Roger Benjamin et al., Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 2009, p.161.

- Jane Raffan, Fair Market Validation: Tommy Lowry, Artifacts Art Services, 2021.

- Hetti Perkins, in Roger Benjamin et al., Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art Cornell University, Ithaca, 2009, p.12.

- Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Papunya Tula: genesis and genius, Art Gallery of New South Wales in association with Papunya Tula Artists, Sydney, 2000, p.185.

- John Kean, Tommy Lowry: Two Men at Kuluntjarranya, D’Lan Contemporary, Melbourne, 2020, p.8.

- Vivien Johnson, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008, p.115.

- Perkins and Kean.

- John Kean, interviewed by Simon Elliott, 27 April 2022.

- Papunya Tula Artists certificate dated 1984; ‘Dreamings’ [exhibition text], 1988; and Sotheby’s Important Aboriginal Art [auction catalogue entry], 2007, in Raffan, p.17.

- John Kean, Tommy Lowry: Two Men at Kuluntjarranya, D’Lan Contemporary, Melbourne, 2020, p.9.

- Fred Myers, Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self: Sentiment, Place and Politics among Western Desert Aborigines, Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986, p.239.

- Kean, p.9.

- Kean, p.12.

- Kean, p.7.

- Raffan, p.28.

- Raffan, p.19.

- Hetti Perkins in Roger Benjamin et al., p.12.

- Kean, p.4.

- Ian McLean, ‘The invention of Indigenous Contemporary Art’, Rattling Spears: a History of Indigenous Australian Art, Reaktion Books, London, 2016, p.340.

- Audrey Li in Henry F. Skerritt, Beyond Dreamings: The Rise of Indigenous Australian Art in the United States, Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia, 2019, p.25.

- Elwyn Lynn, quoted in McLean, p.46.

- Kean, p.9: In a letter dated 18 September 2008, then arts minister the Hon. Peter Garrett AM MP outlined to auction house Sotheby’s Sydney the case denying an export permit for the work Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya 1984: The painting is a rare work of exceptional artistic and historical significance; few works were produced by the artist Tommy Lowry Tjapaltjarri and holdings of works by the artist in public collections are rare; this is the most acclaimed painting by an artist integral to the Papunya painting movement; and this painting is pivotal in telling the story of the history of the Western Desert art movement to Australians. To date, aside from one Rover Thomas painting, Two Men Dreaming at Kuluntjarranya is the only Western Desert painting made specifically for the market to have been denied an export permit, which indicates its importance to the art of Australia.

- Kean, p.9.

- Kean, p.4.

- Kean, p.4.

- Kean, p.13.

Connected objects

Related artists

Metadata, copyright and sharing information

About this story

- Subject