Childlike things: Destiny Deacon snaps blak

By Keemon Williams

'Snap Blak' | 3-2025 | September 2025

Featuring artists such as Fiona Foley, Brenda Croft, Nici Cumpston, Michael Cook and more, ‘Snap Blak’ — a new Collection exhibition of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island photography, at GOMA — shows works seeking to subvert the disempowering, misrepresentative settler–colonial legacy of photography of this country’s First Peoples, and to assert identity, cultural continuity and belonging. Here, photographic artist and QAGOMA curator Keemon Williams takes a personal approach to selected works in the show by the late Kuku and Erub/Mer artist Destiny Deacon.

Like cautionary tales told with a wicked smile and a winking eye, Destiny Deacon’s catalogue of works is a wealth of material for the photographer in me. Her visions arrive like candid memories preserved in an old family photobook. They responsibly wield potent political context without the burden of needing to satiate anyone. Deacon’s bluntness is punctuated by the respect she has for the childhood subject. While so many lens-based artists attempt desperately to take ‘good’ photos, a rare few like Deacon succeed in capturing truthful ones.

Freefall 2001, from her ‘Forced into images’ portfolio, shows an Aboriginal baby doll whose separated head and arms appear to emerge, unnaturally posed, from a white cloud. Deacon’s deliberate choice to frame this image so tightly suggests that the atmospheric shroud is not contained in the immediate view but potentially infinite. It reminds me of ‘the Nothing’, from Wolfgang Petersen’s cult classic film The Neverending Story 1984: a featureless, ever-expanding darkness that encroaches on the land, manifesting as storm clouds. Deacon’s composition wields a similarly ambiguous form. Uncertain if the disconnected doll is in pain or accepting of its fate. The doll’s eyes are merely painted on, but she returns the viewer’s gaze with a knowing glance, mid-flight; Deacon seizes that gaze the same way one would a real-life subject. Anything but gentle, the ‘fall’ appears more like a violent expulsion. To my mind, the scene veers between being a cherub evicted from the heavens, and the sight of a crash-test dummy blown asunder by explosives.

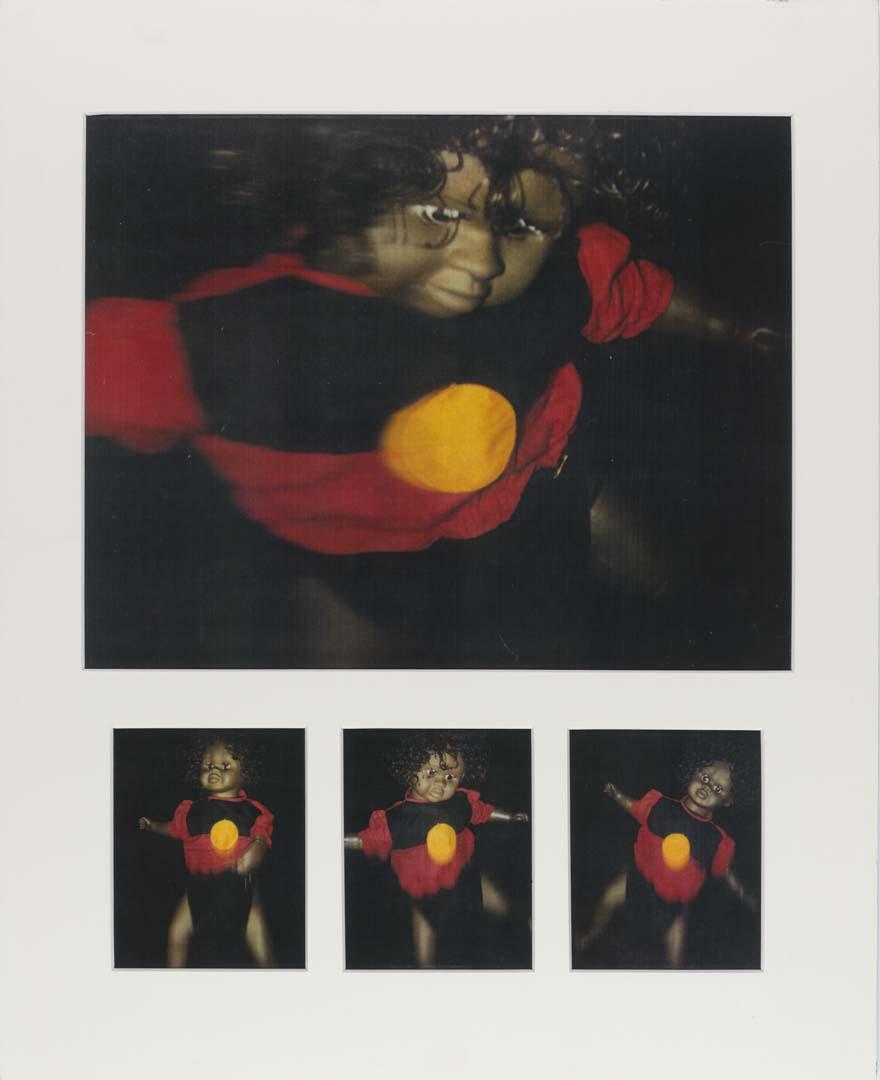

Deacon’s polaroids often weaponise items she has referred to as ‘Koori kitsch’ — including fake cultural objects and stereotyped figurines produced for the tourist market from the mid-twentieth century on — to subvert the lens through which Blakness is perceived and reacted to. In Dance little lady 1993, a doll wearing an Aboriginal flag t-shirt is seen across a series of four images. The title implies that the character might be swaying side to side to the 1971 Tina Charles track ‘Dance, little lady, dance’; its disco aura is palpable. Unlike Freefall, however, this ‘little lady’ is thrust into a pitch-black arena. Although the image threatens to be quite sinister, suggesting that she’s ‘performing’, perhaps unwillingly, for the viewer, I read her exertions as a small, shadowy rebellion — a moment of pure blak splendour. I like to think its darkness is not an absence of light but rather the presence of peace, a moment away from the cultural continuums that label Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as ‘subhuman’. I’m reminded of how, in times of stress, when I really need to kick into gear, I might listen to Donna Summer’s ‘On the radio’ from 1979. Suddenly, I’m not a subject or an identity to be debated, simply a body in motion.

Much of Deacon’s artistic charisma derives from the masterful tension in her scenes, often fuelled by deadpan humour. In Being there 1998, a duo of dolls sits against a darkened corner wall, evoking the image of two cheeky children sitting curbside. One stares deep in thought to the left of frame, while the other looks as though it’s chuckling at a passerby. To their right sits a haphazard scattering of matchsticks. Are these babies in imminent danger? Perhaps they’re the ones in control here. Either way they seem to be having fun, and the artist does love a good bit of mystery. After all, these plastic actors have deceptive range: they can masquerade as anything from players in an Aboriginal tragicomedy to lovable, self-aware little brats. Like Rorschach tests, their perceived motives can change tone with multiple visits. There’s an admitted agony to Deacon’s works, but also the potential for finding something precious in the hurt. Her vignettes remind me to maintain a dialogue with my inner child and to reclaim the immutable optimism the world so easily steals away.1

There’s something heartening about the ability to pick up conversations with artists across time. Destiny Deacon’s artworks feel like precious inheritances that unravel a plethora of visual, material and cathartic blueprints to withstand the crushing weight of life in this country. Across her almost 40-year practice, she generated an unapologetically blak canon, which has inspired so many First Nations artists. I never had the privilege of meeting the artist myself, but I’m immensely thankful for her teachings. I often wonder what the studio she toiled away in would look like, or what she would get up to with an impassioned visitor. I like to think we would have boogied.

Keemon Williams is Assistant Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA. 'Snap Blak' is on display from August 2025 to September 2026 in Gallery 3.5 at GOMA.

Endnotes

- Natalie King, ‘Episodes: A laugh and a tear in every photo’, in Destiny Deacon: Walk + don’t look blak [exhibition catalogue], Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2004, pp.19–20.

Being there 1998

- DEACON, Destiny - Creator

Dance little lady 1993

- DEACON, Destiny - Creator