Cherbourg Aboriginal Settlement

By Lindy Allen, Michael Aird, Paul Memmott

Fred Embrey Research Project February 2024

The Aboriginal reserve then known as Barambah was officially established in 1904 by the Queensland Government, near the south-east Queensland town of Murgon, under The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897. People from numerous clans and tribes from throughout Queensland were forcibly moved there. In 1931, the name was changed to Cherbourg Aboriginal Settlement.

On the settlement, the government administration controlled almost every aspect of these peoples’ lives. They decided whom residents married, denied rights to their lands, censored their mail, compelled them to work for low wages, resettled them by force, removed their children and required residents to ask permission to leave the settlement. Aboriginal people, removed to Cherbourg were either placed in dormitories or lived in camps. Large numbers of children were brought up away from families in the dormitories. Anyone breaking the strict laws were severely punished — either jailed or sent away to other reserves throughout Queensland, such as Taroom, Woorabinda or Palm Island.

It was not until 1986 that Cherbourg became an Aboriginal-controlled Community Council. Handed a Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT), the community began managing its own affairs.

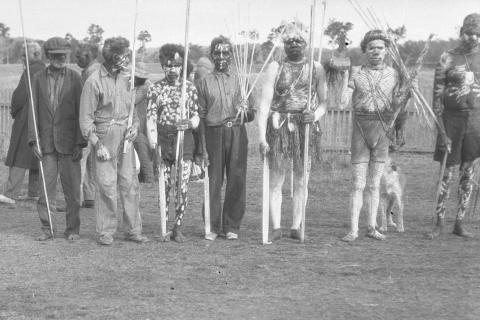

At his son Dinny's funeral, Fred Embrey (second from left) wears a stylised fern pattern is painted on his upper arm; he is holding a softwood shield of the type made by Kabi Kabi men, Cherbourg, 1934 / UQFL489 / Photograph: Caroline Tennant Kelly / Image courtesy: University of Queensland Fryer Library, Brisbane

A legacy of frontier disruption

Kabi Kabi songman Fred Embrey was born into an era of frontier settlement and disruption. The discovery of gold in his Country, in the late 1860s, brought thousands of men to seek their fortunes on the diggings at places like Yabba, Jimna and elsewhere.

When Embrey was first living at Cherbourg in the early 1900s, Aboriginal people of the Mary River and South Burnett region had already experienced several decades of turmoil and upheaval to their way of life after Moreton Bay and the broader region was opened to free settlers from 1842. It was an era marked by violence, with the massacre of untold numbers of Aboriginal people at the hands of settlers and Native Police, led by the infamous Lieutenant Wheeler.1

A major catastrophic event for Kabi Kabi people was the Kilcoy Massacre: the poisoning of some 60 or so of their countrymen who ate damper made with flour laced with arsenic or strychnine, deliberately left in a shepherd’s hut on Kilcoy Station in early 1842. In response, the remaining Kabi Kabi men formed an alliance with their Wakka Wakka and Butchulla relatives, mounting a campaign of resistance against the settlers that lasted for more than a decade.2 Alex Bond, great-grandson of Fred Embrey, recalls his mother Penny Bond talking about a base camp of these resistance fighters on Bribie Island.3

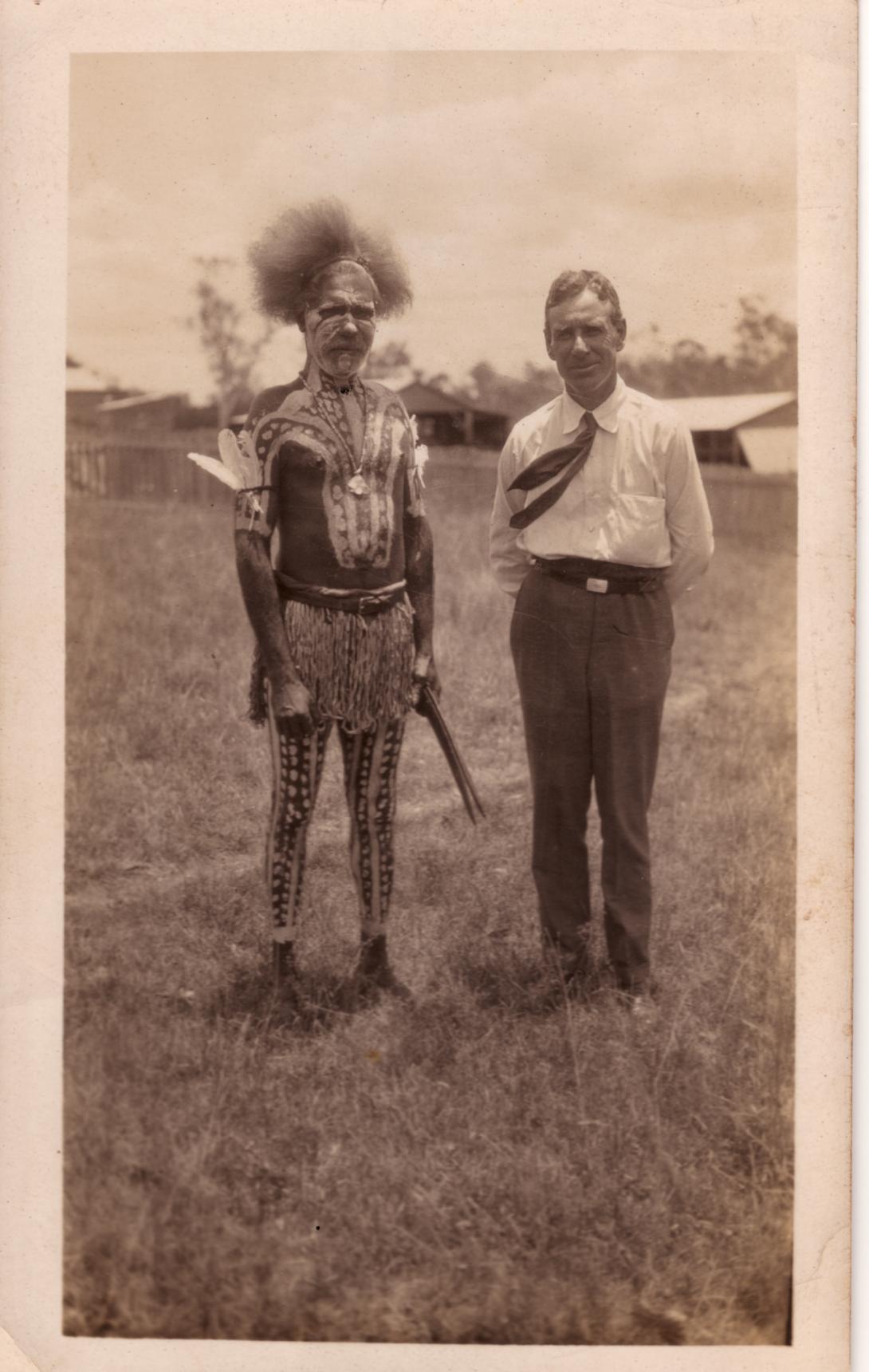

Settlement superintendent Porteous Semple (right) with decorated man, Cherbourg, c.1930 / Betty McKenzie Collection / Collection and image courtesy: Queensland Museum Network, Brisbane

Despite these disruptions, key cultural practices appear to have continued — even if only intermittently — including the ‘kippa-making’ or initiation ceremonies (also known as the ‘bora’ ceremony) where youths were made men. In Two Representative Tribes (1910), anthropologist John Mathew (1849–1929) recalled witnessing this ceremony at Manumbar Station during this time (1865–72), observing that what had been a major ceremonial occasion was by that time ‘much curtailed’.4

According to anthropologist Norman Tindale (1900–93), Tin Can Bay was the ‘place where [Kabi Kabi] had last bora’ and these ceremonies are thought to have continued to at least the early 1880s.5 As an initiated man, Fred Embrey most likely went through these rites around this time.

Fred Embrey wearing his King Plate at Cherbourg, c.1928 / Image courtesy: Cherbourg Memory / URL: https://cherbourgmemory.org/fred-embery-at-cherbourg-aboriginal-settlement-c1930-3 (viewed 17 August 2023)

Fred Embrey’s family at Cherbourg

Embrey married Sylvia Cobbo, a Wakka Wakka woman and daughter of leader Boobijan Cobbo who, like Fred, was a Miva (man of knowledge) at Cherbourg. Their son, Dennis ‘Dinny’ Embrey, died in 1934.

Anthropologist Caronline Tennant Kelly’s photographs of Dinny’s funeral at Cherbourg clearly show Fred Embrey, in traditional ceremonial dress, overseeing the proceedings. Given this major event was conducted on the lands of the mission, it is a tribute to Embrey’s status as a senior custodian that the funeral of his son was carried out with obvious cultural protocols; these images capture a remarkable cultural event in the history of Cherbourg Aboriginal Settlement.

Fred Embrey discussed protocols observed for his son’s funeral with Tennant Kelly:

I am Carpet Snake and my wife Grass Tree. My son was Grass Tree. The reason we danced the Eaglehawk at the funeral is that my father was an Eaglehawk and that’s how we bring my father into it. He is dead and my son will be meeting him so we dance his dream so he will know.6

Fred and Sylvia raised Dinny’s daughter Penny (later Penny Bond), who was born on 21 December 1932.7 They are said to have raised the children of other close relatives, like June Bond (nee Hutton), whose parents were away as part of the labour force provided to pastoral properties from Cherbourg, facilitated under The Act 1897.

Fred Embrey at the funeral of his son Dennis ‘Dinny’ Embrey, Cherbourg, 2934 / Photograph: Caroline Tennant Kelly / Photo album: UQFL489 / Image courtesy: University of Queensland Fryer Library, Brisbane

Access the full research report: FRED EMBREY SCULPTURE RESEARCH PROJECT [39pp PDF 18.5mb].

- See Jonathan Richards, The Secret War: A True History of Queensland’s Native Police, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 2008; and Timothy Bottoms, Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland’s Frontier Killing Times, Allen and Unwin, 2013.

- Alex Bond, Ray Kerkhove and Sean Gilligan, The Statesman, the Warrior and the Songman, ICP Aust Inc., Nambour, 2009, p.22.

- Bond, Kerkhove and Gilligan, 2009, p.9.

- John Mathew, Two Representative Tribes of Queensland, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010; first published in 1910, p.98.

- Norman Tindale, genealogy sheet 30, 1 December 1938, 1938b, South Australian Museum, Adelaide.

- Caroline Tennant Kelly Papers, Series 5 Anthropology Papers, Box 7, Folder 18. Fryer Library, University of Queensland.

- Sylvia Bond, interview with Michael Aird, 23 April 2023.

Explore the Fred Embrey Research Project

Digital Story Introduction

A CEREMONIAL FIGUREFred Embrey: Songman, sculptor, leader

Read BIOGRAPHYDigital story context and navigation

A CEREMONIAL FIGUREExplore the story