Lee Paje: Paradise revisioned

By Abigail Bernal

Artlines | 1-2022 | March 2022

Philippines-based artist Lee Paje is showing two oil on copper works in APT10. Her triptych The stories that weren’t told 2019 and Somewhere, someday when we are the sea 2021 — a suspended 12-panel polyptych commissioned for APT10 — destabilise normative ideas of gender in creation myths and imagine an inclusive vision of paradise. Abigail Bernal first met with Paje in Manila in October 2019, during APT10 research travel. Two years later, in November 2021, they built on that early meeting and subsequent conversations to record a Zoom interview for the opening weekend public programs. This interview was adapted from the recorded conversation.1

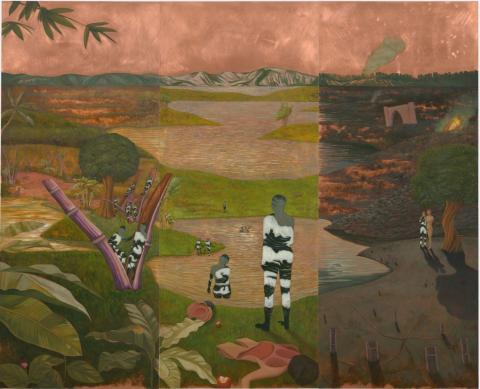

Lee Paje’s The stories that weren’t told 2019, with glimpses (either side) of Somewhere, someday when we are the sea 2021, installed for APT10, December 2021 / © Lee Paje / Photograph: M Campbell, QAGOMA

Abigail Bernal: When we met in Manila in 2019, you told me that The Stories that weren’t told was inspired by a mural you had seen in a hospital as a child.

Lee Paje: The mural I mentioned is by Victor Cabisada Jnr and Peter Alcantara. It is based on the Philippine creation myth called Si Malakas at Si Maganda. The myth explains how the earth was made and how the first man and woman were born from a piece of bamboo.2 The name of the first man is Malakas, which means ‘strong’, and the name of the first woman is Maganda, or ‘beautiful’. In early documentation of this precolonial myth, the names and attributes weren’t at all present — they were added in the mid-twentieth century.

As a young child, seeing the mural for the first time, I was fascinated by the creation myth’s imagery and grand narrative. I remember the nurse at the hospital said that it is about the creation of the very first two people who are meant for each other. And this made an impression on me. Even at a young age, I felt that this does not fit how I see myself and the world around me.

Later I realised how similar, and yet nuanced, the myth is from the story of Adam and Eve. In Si Malakas at Si Maganda, the first man and woman were born at the same time and from the same bamboo, while Adam was created first, and then Eve was created from Adam’s rib. I guess this says a lot about the social status of both sexes in the two different cultures from which the myths emerged.

My triptych The Stories that Weren’t Told is a retelling and mixing of the tropes of these two creation myths. Iconographies and symbolisms from both stories are set into one hybrid narrative to form a new kind of creation myth. In the centre of the image is a lake or body of water. Water also makes up the bodies of the first human beings. Water for me represents fluidity. And identity for me is fluid — gender is like clothing or skin we can choose to wear or discard. In this paradise that I envisioned, there is no first man or woman, only first people.

AB: Somewhere, someday when we are the sea 2021 has a relationship with the triptych, though it takes a different form. How do you see the two works relating to each other?

LP: Somewhere, someday when we are the sea is a continuation of what The Stories that weren’t told is about. The 12 panels are aligned and conjoined to form a panoramic view of different topographies in a continuous landscape. While both works face and echo each other, there is a shift in the mode of looking from passive to active. Viewers are asked to physically engage, to enter and traverse the space. The body of the viewer is a thread that ties the two works together and the meaning of the whole.

Lee Paje’s Somewhere, someday when we are the sea 2021, installed for APT10, December 2021 / © Lee Paje / Photograph: M Campbell, QAGOMA

AB: Your works for APT10 both employ the altarpiece form (a triptych and a multi-panel polyptych) — why was it important to use these forms?

LP: The altarpiece format is often used to tell a narrative, wherein each individual panel tells a different story and — when combined — creates an overarching theme or narrative. As I am retelling these myths, I wanted to use this format to create an alternative where narratives outside the norm can exist. It is also a way for me to empower and validate these non-normative stories.

AB: Can you tell me about the mysterious seascapes?

LP: Water is a way of life for us Filipinos. The significance of water is found in myths, which resonates with Filipino culture and the country as an archipelago. Its visual imagery reminds me of the primordial soup (another creation story). The seascapes and the crashing waves first found their way into my work, and this finally evolved into what I have dubbed ‘primordial people’. I rendered the human body as water or waves crashing in a storm.

AB: How influential is the ideal of Eve or Maganda for contemporary Filipina women?

LP: The ideals of Eve and Maganda are still deeply rooted in the psyche of most Filipinos, especially the older generation. We have been colonised for over 300 years, and these ideals about women were reinforced time and time again through religion, education — even in the media.

AB: Would you say that a focus of your work is to challenge ideas of gender specificity?

LP: I made these works in the hope of retelling stories to include people who are not usually represented in normative stories, like creation myths. The main focus really is to create avenues or alternatives that marginalised people could identify themselves in. The de-stabilising of gendered iconography comes as a result of retelling these narratives.

Abigail Bernal is Associate Curator, Asian Art at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

- This interview draws on many conversations with the artist in the lead up to APT10, and is adapted from a recorded interview from 3 November 2021.

- As Lee has discussed, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his wife Imelda also commissioned portraits of themselves in these roles as a form of propaganda.